Art Review: Rock, Cloth and Scissors - Archetypal forms by Balinese Artist Citra Sasmita

Citation: Mohan, Urmila. “Rock, Cloth and Scissors - Archetypal forms by Balinese Artist Citra Sasmita.” The Jugaad Project, 6 Jul. 2019, thejugaadproject.pub/citra-sasmita [date of access]

Despite having a rich history of aesthetic forms, Balinese contemporary art still remains relatively unknown on a global stage. Being a contemporary artist in Bali can be a struggle between balancing the demands of artistic self-expression with the obligations of community and tradition. In addition, being a woman artist in Bali brings its own complexities with expectations of social (re)production through childbearing and rearing, connection with the family and banjar (village community), and a calendrical cycle of ritual obligations. When thinking of ‘women artists’ in Bali the Kamasan-style painter and priestess Mangku Muriati (born 1967) and the contemporary artist Murni (I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih, 1966-2006) come to mind. In this context, Citra Sasmita (born 1990 in Tabanan, Bali) is one of the few Balinese women artists who is active and widely known in the Java-Bali contemporary art world for her paintings and drawings of women. Citra’s(i) new painting “Metamorphosis: The Flowers of Carnage” in the 2018 “Celebration of the Future” exhibit at the Art Bali venue, Nusa Dua, Bali, continues to explore themes that she is known for—critiques of notions of gender, patriarchy and value.

Figure 1 Metamorphosis (The Flowers of Carnage), 2018, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 150 x 200 cm. Image courtesy of artist.

The painting conveys themes that the artist has long been processing through her previous artwork, such as how to conceive of, and visualize knowledge, and its movement from one generation to the next. Balinese believe in the existence of an invisible world (niskala) which consists of ancestral spirits, deities and demons, as well as a visible world (sekala) beholden to the power of time, materials and decay. The latter, including human bodies in trance (keserupan), can be used to access, appease and channel the power of the invisible. The women in Citra’s painting are not mere mortals but akin to ancestors, represented with allegorical and spiritual powers. Indeed, the artist is emphatic that her art has to communicate through symbols and that the images she uses are part of a visual and conceptual vocabulary.

In Metamorphosis, six partially covered female figures carry symbols of “nature and nurture”(ii) such as a stone, cactus, knife and scissors (Figure 1). In addition, there is the important imagery of the placenta (ari-ari) and cloth with a pattern of gold roses. The placenta is especially central since Balinese believe that the ari-ari is a younger sibling, generally buried close to the house. Drips of paint that look like roots emerge from the women’s feet and they are situated against a background of green. In response to the curatorial call to contemplate the “future”, the caption for the painting states that the future will mean nothing if the next generation doesn’t know their history and philosophy. The new generation should be aware (sadar) and protect their “root” as it forms the tradition for the next generation. In the face of death, disaster and war, human beings must draw on their inherent survival mechanisms to build a better civilization. People need something that will “humanize them like nature”(iii) and one cannot celebrate the future simply through the newness of inventions as “progress” while ignoring negative impacts. In a shrinking world “the rapid development of information and communication technology” must be accompanied by awareness of the “depletion of food resources, clean water and deteriorating quality of environment on earth.”(iv)

Figure 2 Tourists reflected in the window of a photography shop. Ubud, 2018. Photo by author.

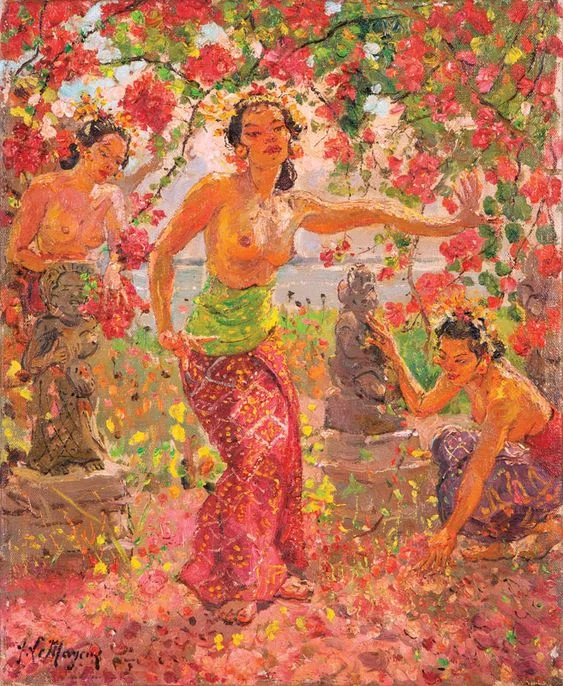

Figure 3 Balinese Women Surrounded by Flower Blossoms. Painting by Adrien Jean Le Mayeur (1880-1958), Oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm. Image credit.

Metamorphosis also provides pause to reflect on Citra’s other works as well as her biography. As the artist notes in an essay the potential of contemporary art is the manner in which it can help Balinese break away from the stultifying consequences of early 20th century Baliseering—a Dutch policy of cultural protectionism envisioned as part of the “ethical” governance of Indonesia. She notes that the paternalistic approach of Baliseering also defined and limited what was considered “art” in Bali, creating a certain stagnancy of aesthetic forms. Against this implicit historical and political background, one encounters the stereotypical use of images of Balinese women from colonial times to the present especially in the service of tourism in the form of postcards, photographs, films and consumer goods (Figure 2).(v) Till today the idealized form of the Balinese woman as an exotic combination of (access to) nature and culture is the preferred representation of the island (Figure 3).

The artist’s biography is an unconventional one. An autodidact studying literature and science, she found her way to art when she was asked to draw illustrations for short stories in the “Bali Post” newspaper. After marriage to a Javanese man and conversion to Islam, Citra left the traditional Balinese social unit or village called the banjar. In effect this act cut her off from the village where she grew up both metaphorically and literally although she does return to visit her relatives. Such a separation gives Citra the freedom to pursue her interests but she also describes a feeling of longing (rindu) for the activities of her youth. This yearning motivates her to make new work that in turn gives her a way to connect with her past as well as the future, especially since she feels that her own generation lacked a proper transition and inheritance of knowledge, for instance, from mother to daughter. Citra also worked with the Bali Women Crisis Centre (BWCC) in Denpasar to heighten her awareness of gender justice, and the perceptions and values accorded to women’s bodies and sexuality. Gender and rootedness as well as forms of emergence and growth thus feature prominently as themes in her art.

Figure 4 Allegory of Desire, 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 120 x 140 cm. Image courtesy of artist.

To focus on one archetype in the artist’s work, consider the use of cloth and the way in which it conveys different meanings. In the painting “Allegory of Desire” (Figure 4) she explores the idea of false identity and how social climbers use their capital to survive. One wonders what capital is being exerted literally in the face of barbed arrows that penetrate the fabric. In “The Act of Curiosity” (Figure 5) cloth acts as a shield, covering and blocking the faces of the protagonists in the painting as well as creating a shared space of intersubjectivity. The message is that sometimes getting knowledge and enlightenment requires a process of looking inward and blocking the senses as well as external stimulation. Images of golden cacti (thorny but also bearing pink flowers) symbolize the glorification of knowledge and the oftentimes painful process by which such enlightenment is gained.

Figure 5 The Act of Curiosity, 2018, Oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 140 x 140 cm. Image courtesy of artist.

The cloth patterns in Metamorphosis are a new symbolic vehicle for the artist. Images of roses are drawn from ornate fabric, commonly known as prada and found in the market. Balinese people often use these in celebrations to wrap trees, figures, and architectural forms. The floral forms themselves have a long history, being derived from Chinese brocades and Manchester-printed cotton imported through centuries of trade. While the fabric that Citra references is not expensive, its effect is opulent and intended to add to the festivity of the occasion. Draping this fabric on human forms in her painting in an unconventional manner allows the artist to imagine new relationships and meanings, for instance, between the act of thinking, weaving and making offerings (called banten) as forms of meditation and memory. In the past, she says, these weavers may have been restricted physically and situated in one place but were mentally able to take flights of freedom through the incorporation of imagery such as birds and animals in their fabric creations. In this context it is not difficult to understand why certain textiles in Bali and other parts of Indonesia are perceived as objects with magical and ceremonial powers.

Figure 6 Image from ceiling of Kertha Gosa, Klungkung, Bali, 2018. Photo by Citra Sasmita.

Resonances can also be found between Citra’s use of cloth as protection and containment, and the use of drapery in mythology. For instance, she showed me a photograph of a Kamasan painting on the ceiling of the “Kertha Gosa” (hall of justice) pavilion in Klungkung (Figure 6), depicting two people covered in cloth. This pavilion was a space that functioned as the meeting, negotiation and judgment place for Balinese royalty and the paintings on the ceiling illustrate the existence of human beings in the three realms of hell, earth and heaven. The subjects in the painting (Figure 6) are depicted as living in the middle realm of earth. In this realm, human beings experience procreation, birth, and sickness/death, with constant threats as symbolized through the arrival of a monstrous creature from above. Citra shared her analysis of this painting as one where the two protagonists’ bodies are entirely wrapped for protection from invisible but lethal forces.

Figure 7 Cacti as protection at the entrance to a house. Ubud, Bali, 2018. Photo by author.

The work of rooting one’s art to the past through personal experiences and beliefs connects Citra not only to her personal history but to broader practices and spaces that could be defined as “Balinese culture”. While she appreciates the beauty and philosophy of Balinese rituals (and aesthetics), there are occasions on which the artist also rejects any direct association of such ideas with her work. For instance, the traditional concept of charisma (taksu) is often used by Balinese to explain the success of any endeavor. Every traditional house includes a shrine (pelinggih) for taksu as part of a constellation of deities and ancestral spirits. Citra describes taksu as an “antenna” that serves to connect people with the realm of these efficacious powers. However, praying at this shrine does not form part of her creative practice as Citra emphatically states that she is already successfully tethered to the universe through her creative practice.(vi)

As mentioned briefly earlier in this article, Balinese contemporary artists must contend with pervasive stereotypes in order to innovate especially when dealing with issues of gender and cultural identity. Against this backdrop, Citra’s works are valuable archetypal evidence of how contemporary art can truly help revitalize old forms and create fertile spaces of freedom and expression.

Acknowledgments

The research conducted for this article was supported by a 2018-19 fellowship to study textiles in Bali and Java from the Asian Cultural Council.

Notes

(i) I refer to the artist by this name in keeping with cultural practices in Bali and Indonesia where people may be simply known by one name.

(ii) Personal communication with the artist, December 16, 2018.

(iii) Ibid

(iv) From the label for the painting Metamorphosis, 2018.

(v) For more on the historical role of Dutch colonial policies and the effects of tourism on the island’s culture see Adrian Vickers. 1989. Bali: A Paradise Created. Australia: Penguin Books.

(vi) Conversation with the artist, December 18, 2018.