Colorism, Castism, and Gentrification in Bollywood

Abstract

Colorism, prejudicial attitudes towards people with darker skin tones, like all -isms, creates a toxic environment for anyone who does not fall into the ideal category. When major media sources, like Bollywood in India, reinforce the oppressive attitude of discrimination based on skin color, it adds to the normalization of colorism and resulting social hierarchies, perceptions, and stigma. Moreover, Bollywood and its films are not consumed in a vacuum. In the current environment of Black Lives Matter, especially following the killing of George Floyd in the U.S. and the subsequent international protests, it is pressing to highlight the ways in which Bollywood contributes to biased and marginalizing practices of colorism, as a form of racism. This is especially important given the number of Bollywood actors, directors, and producers who publicly denounced racism in America, offering solidarity to Black Americans, while staying silent about the prejudice happening in their own communities. In this article, I will focus on colorism in India. India’s film industry actively reinforces and reproduces colorist attitudes; commodifies colorism; and disenfranchises women, lower castes, and indigenous people. There is a disconnect between the progressive values publicly stated and those practiced by leaders in Bollywood. I argue that Bollywood’s desires for respectability among upper class Indian and diasporic audiences emboldens its attitudes about class, caste, and color, contributing significantly to the power and reach of colorism.

Citation: Peters, Rebecca. “Colorism, Castism, and Gentrification in Bollywood.” The Jugaad Project, 24 Feb. 2021, thejugaadproject.pub/colorism-bollywood [date of access]

Introduction

Colorism, the prejudicial attitudes and discrimination towards people with a darker skin tone, typically among individuals within the same racial or ethnic group, affects millions of people across the globe. While racism and racial bias discussions occur in many media forums today, especially in the wake of the prescient Black Lives Matter movement, colorism receives much less attention. Nevertheless, it is a pressing issue in America and across the world. The basis of colorist attitudes center around the concept of “whiteness” and “lightness” as ideal, as discussed below. This article will focus on India, and specifically on colorism within cinema and mainstream media. By focusing on the film industry this paper traces how cultural and religious norms are appealed to or used, directly or indirectly, in perpetuating colorism against the backdrop of economic and industrial change.

Colorism has a long history in India. The association of skin color with caste, class, and morality that is reified in Hindu religious and cultural symbols and rhetoric allows colorism not only to be prevalent, but also to be practiced unabashedly among most of the population. Today, because of the pervasiveness of media in all aspects of life, even in rural locations, colorism has become more pronounced. In this environment Bollywood, the largest and most pan-Indian commercial film industry, serves a unique position of being both passively cognizant of the problem of colorism and actively entrenched in its ideals and perpetuation. To address this position of Bollywood and colorism in India, I will first establish the historical and religious links between color and caste, and then address the contemporary use of colorism in Indian media. I will then focus on Bollywood’s role in colorism both on- and off-screen, finally looking at the impact such representation has on women in India. I argue that the film industry actively reinforces and reproduces colorist attitudes, commodifies colorism, and disenfranchises women, lower castes, and indigenous people. Bollywood producers, directors, and actors use colorist attitudes not only to protect their position of power, but also to help establish credibility among urban elites, their target audience. Despite publicly recognizing and critiquing discriminatory attitudes about skin color, Bollywood maintains its colorist position to curry favor with the upper class, Indian diaspora, and the West, implicating the US and Hollywood in its own colorist attitudes.

On July 16, 2020 Netflix released a new original reality series entitled Indian Matchmaking, to very mixed reviews. The critiques and the acclamations dealt with the same issue: the manner in which the series lays bare South Asian sexism, casteism, and colorism. Sima of Mumbai, the Indian matchmaker and central figure of the series, matter-of-factly states her adages of Indian society and marriage. She unabashedly affirms that people are “good matches” because they are fair, tall, and come from a good family. Good becomes a loaded term to mean both well-matched and moral; at the same time, fairness and caste (the underlying meaning of a good family) are also consistently equated with goodness. Nath (2020) and other critics of the series point out that by not featuring any alternative voices even within this reality TV format, Indian Matchmaking endorses views of colorism, sexism, and casteism. Instead of highlighting these problems, the show normalizes and even celebrates them.

However, these critiques, as important as they are, overlook or gloss the connection between the phenomena of gentrification in India and the Indian diaspora in the U.S., where good also connotes elite and upper-class wealth and consumerism and the ways in which Bollywood’s economy sustains colorism. Liberalization of the Indian economy in the 1990s created a rise in Indian middle and upper-middle class. This upper-middle class embodies Western ideas of success and wealth, creating gated neighborhoods, consumerism with vast shopping malls, and a reflection of their ideals and lifestyle in Bollywood films (Brosius, 2010). Media Anthropologist Tejaswini Ganti (2012) argues in Producing Bollywood that since 2000, Bollywood insiders (producers, directors, actors, etc.) have re-branded Hindi cinema as integral to the consumption habits of the growing middle class, choosing to highlight lavish lifestyles rather than “the signs and symbols of poverty, labor, and rural life,” and themes of “class conflict, social injustice, and youthful rebellion” (29). Ganti observe how these filmmakers desire respectability especially among the elites of India and the West; they want the reputation and value of their Hollywood counterparts. As such they engage in discourse that elevates their behavior from previous generations of filmmakers and filmmaking practices, often complaining about the Indian “uneducated masses” for whom they make films [1]. Ganti calls this shift in cinematic themes and rhetoric among the people of Bollywood the “gentrification of Bollywood” (2012, p. 81). However, films which now appeal to young, urban middle class and diasporic Indians, which favor rich and elite lifestyles also reinforce strict ideas of caste, class, and colorism.

In addition to erasing the representations of the poor, rural, and working classes from the films, the changes in Hindi filmmaking—cited by industry members and observers as modernizing and becoming more sophisticated and fashionable—have also been responsible for erasing the actual presence of working class men and women in the profilmic space (Ganti, 2017).

The main contribution of this paper will thus be to explore the disconnect between the liberalism and progressive values articulated by Bollywood producers, directors and actors, and the blatant colorism exhibited which is supported in turn by a range of socio-economic and cultural factors including beliefs associated with Hinduism [2].

Colorism and Casteism: A Historic Perspective

The term colorism has been widely been attributed to Pulitzer Prize winner and activist Alice Walker in her 1982 essay “If the Present Looks Like the Past, What Does the Future Look Like?” (Jones, 2000) and was originally invoked in the context of colorism among and against black communities in the US [3]. While the term is relatively new, the prejudicial behavior has been around for centuries. Unlike racism, colorism is definitively aesthetic, the skin tone, facial features, and hair textures all play a part in establishing bias. Also, people within a racial or ethnic group regularly practice colorism, idealizing lighter features over darker.

Colorism exists across the world, not just in South Asia. Whiteness, and its global privileging, resulted from years of British and European colonialism during the 14th through 19th centuries, coinciding with imperialism, mercantilism, slave trade and indentured labor. Discussions surrounding discrimination establish links between white privilege, racism, and colorism (Dhillon-Jamerson, 2018; Mishra, 2015; Begedou 2014; Russell-Cole et al. 2013; Levinson and Young, 2010). As many scholars have pointed out, the category of race and racial sciences was created during the age of Enlightenment by colonizers who wanted to justify slavery and colonization while simultaneously establishing the “inherent rights of man” (Said, 1993; Morrison, 1992; Connolly, 1991; Todorov, 1984; Jordan, 1977; Davis, 1975 in Omi and Winant, 1994). The category of race, and the prioritization of Whiteness, solved this problem. By positing that those who lived in different climates and held different physical features were less human, scholars could create a racialized science that ignored their contradictory positions. Shortly after this time Charles Darwin published his Origin of the Species in 1859. White scholars quickly took to evolution as the link between their whiteness and innate humanity. With Darwin’s theory of evolution, men could argue that whiteness was the ultimate evolutionary position; that anyone not white was not fully evolved (Omi and Winant 1994: pp. 63-64). In this environment, Whiteness becomes a marker as well as the embodiment of the ideal human, race and color. During the 18th century, as Mechthild Fend (2017) and Anne LaFont (2017) explain, science and art begin to make distinctions of color to attribute racial differences. Color becomes a way to articulate racial differences. For centuries Whiteness and associated forms of privilege and power such as lightness within a racial group has been the standard for beauty, intelligence, status, and integrity across the globe (Dhillon-Jamerson, 2018). This explains how even in African countries, which have suffered under generations of colonialism, lightness and proximity to Whiteness become romanticized as beautiful and pure (Pierre, 2012) [4].

In a feature for The New York Times Magazine, written in response to the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests, journalist Isabela Wilkerson (2020) describes the historic systemic and ideological racism in America as an “enduring caste system”. Wilkerson’s association of systemic racism with caste resonates in India where the structures of Indian society surrounding the Hindu caste system amplify and maintain colorism.

South Asia, as a former colony of the British, French, and Portuguese, similarly fell victim to racial bias and dehumanization of the populations living there. However, colorism in South Asia also thrives on ideas of caste and purity. The trauma of colonialism in South Asia cannot be understated, nevertheless colorism and its link to casteism existed in some manner for centuries before the British arrived. This association of color with caste has two equally destructive consequences: 1) it reinforces casteist ideas of hierarchy among people groups, whereby lower castes are less desirable; and 2) this association with a religious rhetoric of status and purity excuses those in power from addressing any resulting social problems.

Ancient South Asian civilization, while far from uniform in their religious attitudes or teachings, predominantly practiced a form of what is today called Hinduism (for a broad overview of Hinduism, see Doniger, 2009). “Hinduism”, itself a colonial construct, does not have a central universal text, but there exist certain core teachings and narratives. The Vedas, Upanishads, Dharmasastras, Ramayana, and Mahabharata not only describe behavioral and theological expectations within Hinduism, they also describe certain life experiences from ancient times. It is among these texts that the association of color with caste first appears. In fact, the Sanskrit word varna, which describes the four main groupings – Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Sudra – means color (Singh, 2014). The “color” here likely meant the colors associated with power (red for passion, white for purity, black for darkness). It should be noted that the Vedas, the texts which first discuss varna, do not create the hierarchy of varnas in the way that it is understood today. Rather, each varna served a different purpose in society, and was associated with social position more than birthright (Singh, 2014). These varna groupings center around rules of purity and religio-morality. As ethnosociologists of India have pointed out, the Hindu body is porous and can be altered through contact with pure or impure substances (McKim Marriott and Ronald Inden in Mohan, 2018: pp. 4, 49). Those in the upper castes of Brahmin and Kshatriya must be especially careful of contact with those of the Sudra lower caste and the Dalit, untouchables. Appearances, aesthetics, bodily practices, caste, morality and ethics are thus all intricately tied together.

Furthermore, as Hira Singh points out, caste has historically also been about class stratification, not simply religious hierarchies.

[T]he division of labour associated with caste is dictated not by the realm of the sacred so much as by the monopoly of economic and political power exercised by the upper castes in the profane, material world. It is, in short, the dependence of impure castes on the pure for their means of subsistence that compels the former to do the unclean jobs. Religion only legitimates this arrangement. No wonder that Brahmin apologists such as Kane [1974] treated the differences between jatis as differences between natural species [cf. Chatterjee,1989: 183]. Dominant ideology represents the social difference between unequal groups—caste, race, gender—as natural and thus unchangeable [Beteille,1981] (Singh, 2014).

Discussions of caste and class, therefore, have been intertwined for millenia, with lower castes being associated with tasks considered unclean for the upper classes. Since ancient India was a rural agriculture society, the majority of labor was outside, being performed by lower caste people. Meanwhile the owning and ruling castes remained primarily indoors, at homes or temples (Chakravarti, 2018; Singh, 2014). It is not surprising then that in a predominantly agricultural society, skin color would come to be associated with class and education. Living inside, hidden away from the sun, was a class advantage in times when work took place outdoors (van den Berghe, 1986). One can easily understand how fieldworkers would develop darker skin than those working in buildings, and how that would facilitate the association of darker skin tones with a lower class and caste status (Singh, 2014).

One common critique of ancient colorism in India is that gods, goddesses, and avatars were described and depicted as black and dark in positive ways (Mishra, 2015). The epic narratives of the Mahabharata and Ramayana describe important gods and avatars as dark. Nevertheless, this alone cannot serve as a counter to the discussion of colorism in ancient times. First, exceptionalism of one or a few rarely, if ever, demonstrates an equality among the many. This can most clearly be seen in the stark difference in the way patriarchal societies respect and honors goddesses compared to women (Doniger, 2009; Erndl, 2000). Second, unlike in Abrahamic religions, the gods and goddesses of Hinduism are not meant to serve as role models for human behavior. They exist across time and space; therefore, their goals and behaviors cannot be reconciled with a short-lived human. Third, it is widely believed that aspects of Hinduism arose from a syncretic relationship between nomadic Aryans and indigenous groups, resulting in many of the darker depictions of gods (Chakravarti, 2018; Singh, 2014). However, this syncretic relationship was not an equal one, and despite appropriating many of their gods, the indigenous people were predominantly vilified and ostracized for their darker skin and behaviors. These ancient scriptures and epics regularly depict the lower and untouchable castes as dark, beastly, and undesirable. Finally, in contemporary times, while they continue to be described as dark, Vishnu (and his avatars Ram and Krishna) and Shiva almost exclusively are drawn or painted as blue, and typically light blue, rather than black. Instead of serving as a counter to colorism, these gods and their depictions reify colorism by maintaining typically Aryan (white) facial features and very light blue skin (for instance, depictions of Krishna in the global ‘International Society for Krishna Consciousness’ ISKON), while continuing to be called dark and black in the literature. From this perspective, “dark” at its best mimics whiteness in all ways.

To whatever extent the ancient civilization drew associations between color and caste, no one can deny that this was exacerbated by the colonial rule of the British for over 200 years where lighter-skinned Indians were given opportunities to work in government, had greater access to education, and were treated better by the ruling English. This led to systemic prioritization of light skin in Indian society (Mishra, 2015). Furthermore, because the British attempted to understand Hinduism through a strictly Brahmanical perspective, they set about codifying the caste system, whereby Brahmins held the highest esteem and Sudras the lowest, with Dalits being outside of the system. The British believed that the Brahmin caste, as the priestly caste, held key information as to what was Hinduism. The British were quick to reinforce ideas of color, caste, and class, with the darkest “Black” Indians believed to be the lower castes, since it upheld their own racist viewpoints of the world (Mishra, 2015: 731). Therefore, by the time the British left India in 1947, more than five generations of Indians had internalized this extreme system of color oppression [5].

Contemporary Colorism and Media

In post-colonial India, those in charge benefited from colorism. They continued to perpetuate this belief system through similarly prioritizing lighter-skinned Indians for education, government work, and media representation, furthering associations of color with class (Rehman, 2019; Mishra, 2015; Singh 2014). Religious representation also reinforces association of caste with class and skin color. Bazaars teem with images of the Hindu pantheon. Post cards, calendars, shirts, bags, and small figures all promote Hindu deities. Sometimes these images become the focus of household shrines; sometimes they serve to watch over a car, rickshaw, or bicycle; and sometimes they simply reside on one’s body. These images, regardless of their purpose or region, or who they depict, present light-skinned deities, as mentioned above (Jain, 2007; Pinney, 2004, Davis, 1997).

Unsurprisingly, skin lightening is a multi-million-dollar industry in India. Brands such as Olay, Ponds, Lakme, and others produce fairness and skin lightening creams, facewashes, serums, and facial bleaching products throughout India. Unlike in many places in Africa and America, these fairness creams are not shameful or embarrassing in South Asia (Pierre, 2012; Gopinath, 2012). Instead they are considered lifestyle aspirations, supported by the burgeoning middle class and associations of fairness and goodness (Shroff et al., 2019; Jha, 2016; Nadeem, 2014; Brosius, 2010). In an industry worth more than $300 million USD, advertisements can be found on posters, billboards, television advertisements, and commercials are aired before movies in the local theaters. In their desire to increase market share, these ads target men as well (Mukherjee, 2020; Venkataswamy, 2013). Further aligning lightness with economic success, Bollywood actors and actresses regularly endorse creams such as Fair and Lovely and Garnier Light Ultra (Jha, 2016). The language of the advertisements presents fairness as a quality to be desired, equal to beauty, while darkness as being something to “overcome” or “transform” (Shroff et al., 2019; Jha, 2016; Nadeem, 2014). In a study conducted by Neha Mishra, over 55% percentage of women admitted to regularly using lightening creams to help with their goals of education, promotions, and finding a suitable partner, despite knowing the risks of blood poisoning and cancer, among other health factors (Shroff et al., 2018). The effects are so negative that some consider the promotion of fairness creams as a sort of “disease mongering” that opportunistically exploits a widespread anxiety (Shankar et al., 2006). And 77% of men stated that light skin was a component of prettiness (Mishra, 2015). In fact, the term complexion is frequently used as a euphemism for skin color in India rather than simply appearance.

In 2013, actress Nandita Das helped re-launch Dark is Beautiful, a campaign to promote healthier representations and attitudes of dark-skinned people (Jha, 2016). Despite a significant positive response from Indian girls and women, the movement has been largely unsuccessful in making any great changes in society or consumer habits, especially against the fairness creams that abound. However, in the current moment, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, Unilever, the biggest producer of fairness creams, has come under fire. In response, they have decided to change the name of their products, from Fair and Lovely to Glow and Lovely. Similarly, Johnson and Johnson have considered pulling fairness products altogether from their Asian markets (Pandey, 2020). While many people are unhappy with these plans, nevertheless, the fact that media outlets are beginning to pay attention to the problems has potential for enacting real change.

Colorism in Bollywood

Bollywood producers and directors maintain strong ties to their religious heritage. Many films reference or re-enact stories from the epic narratives, such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Hindu shrines and altars abound on film sets and in production rooms and “…religious practice is integrated into the inaugural rituals of every film production. …shrines and altars [are] in active use at many of the film production companies and individual artist’s studios” (Vasek and Chatterjee 2020). Belief in the auspiciousness of deities and their images (murtis) cannot be overemphasized and a scene from the documentary Bollywood: The World’s Biggest Film Industry (2018), shows how director Alphonse Roy starts his day with ritual prayer to the elephant-headed god Ganesh along with the film camera focused on the deity. It is beyond the scope of this paper to explore how modes of worship such as darshan (embodied gaze between deity and devotee) relate to colorism, but it is worth noting that the Bollywood ‘sensescape’ emphasizes visual spectacle and sensation whether of locations or bodies

Figure 1: Screenshot of ritual on set in Bollywood: The World's Biggest Film Industry documentary.

Figure 2: Nandita Das, Photo by Nandita Das - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0. Image source.

Along with a close association with Hinduism, current Bollywood films regularly present successful upper class and upper caste lifestyles. The gentrification goals of appealing to the upper class include reinforcing associations of class, caste, and color. Despite there being many different skin tones and shades in India, Bollywood continually casts lighter-skinned actors. Foreign actresses have become cast in main roles despite their lack of film experience or knowledge of Hindi because of their whiteness (Ganti, 2017). And for those actors who do not meet the degree of lightness the director and producer desires, they are pressured to use fairness creams and makeup to lighten their skin. Countless activists have complained about this persistent problem, calling on Bollywood to acknowledge their role in perpetuating colorism in India (Arora 2015; Bhattacharya, 2020; Ganapathy, 2013). Articles have pointed out the issues of colorism in Bollywood, drawing attention to how actors and actresses continually must lighten their natural tones to appear in films. Successful actress and director Nandita Das, mentioned above, has lost roles because of her refusal to whiten her skin (Dutta, 2019; Ganapathy, 2013).

Figure 3: Priyanka Chopra, before Hollywood work, at the Launch of Dabboo Ratnani's Calendar 2012. By Bollywood Hungama, CC BY 3.0. Image source.

Priyanka Chopra, despite winning the title of Miss World, was not considered beautiful enough to appear in mainstream films without lightening her skin. Chopra’s case is one of the most apparent because, since becoming popular in Hollywood, she has stopped whitening her skin, even when working in India. A side-by-side comparison of Chopra’s previous and current films show a marked difference in skin color (Bhattacharya, 2020). This is a case in point for a situation where the cultural power of Hollywood and global (that is, Western) acceptance of the actress supersedes more regional ways of construing her value (both aesthetically and economically). Thus, this brings into question the seeming rigidity of colorism in India and whether it should be approached as a fixed entity or as part of an intersectional relationship of power that is constantly changing?

Figure 4: Priyanka Chopra at a promotion event of the film Umang in 2020. Photo By Bollywood Hungama, CC BY 3.0. Image source.

When a darker-skinned actor is hired, especially in North Indian films, they are used as a villain, and this is usually only true of men (Ganapathy 2013; Mishra 2015). Occasionally dark-skinned actors’ talent allows them to find work in more independent roles as main heroes. For example, Nawazuddin Siddiqui is a celebrated actor whose talent is regularly lauded by critics and audiences alike. Nevertheless, until recently the majority of roles that Nawazzudin played in mainstream films were evil. He has even been told publicly that he cannot be a romantic lead because of the color of his skin (Sharma, 2019). In 2017, casting director Sanjay Chouhan made the following statement about Nawazuddin: “We can’t cast fair and handsome people with Nawaz. It would look so weird. You have to take people with distinct features and personalities when pairing them with him” (Arora 2015). Even in his latest film, the Netflix release crime drama Raat Akeli Hain, characters comment on his dark color. Early in the film, a woman refuses his photo as a potential mate citing his color (rang), by saying he is not “clean” (saaf), which is subtitled in English, “he is dark-skinned.” Shortly after, he uses lightening creams, while in the background his mother discusses his color as being problematic to finding a wife. Despite the fact that the film ultimately has him throw out his lightening cream, the manner in which he does so loses any efficacy of commentary [6]. This demonstrates how there is a slippage between skin color (rang), appearance and character (not clean), and how colorism is blatantly pervasive in Bollywood.

Figure 5: Nawazuddin Siddiqui. International Indian Film Academy awards Green Carpet (MetLife Stadium) in East Rutherford, New Jersey, 2017. Photo by By Laura Lee Dooley from Arlington, VA, USA - IIFA 2017 Green Carpet, CC BY 2.0. Image source.

Bollywood’s lack of diversity in representation does more than simply present a single type of beauty as desirous. Bollywood is one of the largest film industries in the world by viewership (Matusitz and Payano, 2011). People across the world, especially in South Asia, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean regularly watch Bollywood films. The vast majority of viewers fall into the category of non-white. They look to Bollywood for trend setting, fashion choices, hair styles, and for information about what constitutes beauty. Films provide a cultural pedagogy that influence audiences through both overt and covert messages of acceptability, beauty, and normalcy (Kellner, 2003). Beyond this, in India, deification of Indian actors, actresses, and films regularly occur. When Bollywood not only provides only extremely light-skinned actors as the heroes and heroines, but also casts darker-skinned actors as villains, seducers, and scoundrels, messages about color and value get transmitted to all who view these films. Further, films stereotype lower caste groups as darker skinned, uneducated, and often foolish, creating associations between skin tone and caste, as well as class. One clear example of this is in the film Chennai Express from 2013. This blockbuster film starring Shah Rukh Khan and Deepika Padukone, two very light-skinned actors, predominantly takes place in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu. This comedy presents all the main characters as having light skin tones. However, all of the villains, buffoons, and mobsters have dark skin. Since half of these villains are supposed to be cousins of Deepika’s character, the color difference is not only striking, but clearly intentional. Bollywood regularly reinforces deeply biased views about color and caste as markers of beauty and sophistication, leaving everyday Indians with little choice but to compare themselves against such impossible standards.

Use of Brownface and Depiction of Indigenous People

One of the more insidious ways that Bollywood perpetuates colorism is through using brownface on lighter-skinned actors when having them depict lower class, lower caste, or indigenous people in main roles. Instead of having a darker-skinned or indigenous actor play these roles, producers use brownface on a popular actor or actress. The term brownface, where actors wear heavy makeup to darken their skin color, likely brings to mind the term blackface from American film history. Blackface in Hollywood remains rightly stigmatized because of its association with minstrelsy and caricaturing of Black Americans. Blackface was used as early as the 1920s by white Hollywood stars to mimic black music and dancing. Unsurprisingly, the roles reinforced bigoted and stereotyped assumptions about the black community. Blackface was a tool used by those in power to maintain the status quo in a racially segregated America (Lott, 1996). While brownface in India does not include nearly the negative history, nevertheless, it is an offensive way to omit a whole section of Indian representation. Instead of using a broader diversity of darker actors and actresses, Bollywood uses the same popular light-skinned actors in those roles. This is more akin to whitewashing in Hollywood, where popular white actors are given roles that are written for non-white characters. Like in Hollywood, Bollywood producers can then claim that their storylines include diverse characters and themes without actually providing diverse representation. Once again gentrification within Bollywood results in a reinforcement of the status quo, while arguing that they hold progressive views.

Indian directors argue that brownface is useful since these are well-known actors, and their star power remains to draw in the audience, despite their darker skin (Chatterji, 2019). This action is especially problematic given which characters directors believe it necessary to darken. The characters are almost exclusively lower class, lower caste, and often Muslim or indigenous. The skin color is a code to the audience that these are people who are less than, creating an additional indication of the quality of their transformation. Big blockbuster films in the past several years that have had the main characters in brownface, include Udta Punjab (2016), Gully Boy (2019), and Super 30 (2019).

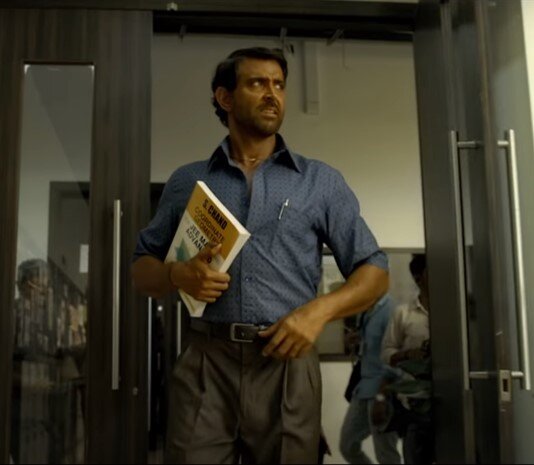

Alia Bhatt plays a Bihari migrant worker who is forced into prostitution, Ranveer Singh plays an impoverished who lives in the slums of Mumbai, and Hrithik Roshan acts as a lower caste and lower-class mathematics educator, respectively. The fact that only lower class and lower caste characters, often exaggeratingly impoverished, are presented in this way furthers the implicit bias of skin color as a marker of class and caste respectability [7].

Figure 6: Hrithik Roshan in Super 30, 2019. Screengrab of trailer on YouTube by author.

A further dangerous way that Bollywood reifies colorism is through the manner in which they tell biographical stories of darker Indians and indigenous people. Adivasis, or Scheduled Tribes, are indigenous people who are marginalized in much of India. They make up about 9 percent of the population but are rarely seen in any kind of media portrayal [8]. Since Adivasis exist across the country, all indigenous people do not look the same. Nevertheless, films that do have Adivasis almost exclusively portray them as black savages, primitive, and ignorant. For example, the 2007 film Chak De! India, a film that celebrates the diversity of all types of Indians, includes two Adivasis from Jharkhand, but they cannot really speak or understand Hindi and barely appear in the film. In 2015, the film MSG 2 the Messenger presented the Adivasis as “devils” (Dungdung, 2015) that must be transformed into humans [9]. When Bollywood does take on a story of esteemed Adivasis, their culture is almost entirely erased. Aamir Khan’s character, Rancho in 3 Idiots (2009) is inspired by the Ladakhi engineer and educational reform activist, Sonam Wangchuk. Not only is the character played by an upper caste light skinned Aamir Khan [10], but Rancho’s family and culture are barely mentioned [11]. This stands out against the in-depth family discussions of all the other main characters (Bhagat, 2018). Probably the most egregious offence is the biopic of Mary Kom Hmangte. Mary Kom Hmangte is a Manipur tribal boxer who has won numerous prestigious national awards, including the World Amateur Boxing Championship. While the film, Mary Kom, received numerous awards for its portrayal of a strong woman, nevertheless, it glosses her Tribal heritage.

Figure 7: Priyanka Chopra and Mary Kom at a release of the film Mary Kom. Photo by Bollywood Hungama, CC BY 3.0. Image source.

Not surprisingly, in the 122 minutes long movie, they wiped clean almost all the overt references to her tribal identity, barring [sic] two scenes, [which] barely last[ed] a couple of minutes. They implicitly hinted about her tribal roots in the northeastern state of Manipur (Bhagat, 2018).

While Mary Kom Hmangte is not dark skinned, her portrayal by actress Priyanka Chopra reinforces the same problem. Instead of providing a diversity of Indian features and people, only one type of Indian is considered acceptable, that which closely aligns with Aryan “white” features.

Moral Positioning and Economics

An important way to gain respectability among Bollywood elites includes presenting themselves as advocates of progressive ideas, especially those encouraged in the West, such as gender equality, queer acceptance, and concerns with the impoverished. Despite the number of films which reinforce the status quo, Bollywood puts forward this face of social progress. Bollywood actors, actresses, directors, and producers often advocate for social programs and create films that deal with social ills. Aamir Khan, Ayushmann Khurrana, and Akshay Kumar regularly make films that deal with issues of poverty, discrimination, and gender [12]. Aamir Khan also ran a documentary-style television show, Satyamev Jayate, that highlighted a different social issue every week. Nevertheless, the industry as a whole, and even within many of these productions, reproduces hierarchies and discriminatory attitudes, especially dealing with colorism. All three of these superstar actors have played characters whose role should have gone to a darker actor, either because of the biographical nature of the work, or the region in which the story takes place. In fact, Khuranna’s Bala¸ which deals with male pattern baldness, has a secondary storyline about color and discrimination. However, instead of casting a darker actress in the role, they cast Bhumi Pednekar and darken her skin (Chatterji, 2019). Despite arguing within the film that women should not be discriminated against for their darker skin, the filmmakers discriminated against a dark-skinned actress.

The producers, directors, and investors in Bollywood absolutely hold positions of power, which instils a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Nevertheless, more than hegemonic fragility is at work. As previously stated, current filmmakers and actors desire for their work to be recognized as legitimate, similar to Hollywood (Ganti, 2012; pp.217-217). The promotion of social responsibility is one of the many ways that the industry appeals to the young urban and diasporic Indian audience. However, part of this gentrification of Bollywood includes removing signs of poverty, crime, and social injustice from the films (Ganti, 2012; pp.29, 81-90). To satisfy the new target audience, the middle-class urban elites and diaspora, when a film does addresses issues, it is sanitized in order to maintain its popularity (Brosius, 2010). Rural India loses the rough edges, even while pointing out the lack of toilets [13]. It should also be noted that these social issue films often coincide with goals of the government, often including nationalistic Hindu discourse as part of the narrative. In this way, the associations of Hinduism, class, caste, and color reify the implicit bias of and upper caste as urban and light-skinned within these social films, even when addressing issues of the poor and the lower caste.

Film makers and producers in Bollywood, much like in Hollywood, will adamantly deny prejudice and bias as goals of their productions. Instead, they argue that the market decides these things. Many filmmakers will agree with the problems of colorism and casteism, and they will state that they do not hold such beliefs. They argue that audience members want light skinned heroes and heroines, and they will not attend films that do not conform to these expectations. The argument, then, becomes about economic motivations, rather than moral or ethical ones. Unfortunately, economic arguments for maintaining the status quo have long been used by hegemonic forces to maintain their power and position. These same arguments are used for why films must have a strong male lead and a known actor (Sharma, 2019; Sarkar 2020; Dutta 2019). And to a certain extent, they are correct. The current system profits when fulfilling normative expectations: light-skinned, known male lead and equally or more light-skinned, young, known female love interest or counterpart. The most financially successful films include this formula (Sanju, Tiger Zinda Hai, Dangal, Bajrangi Bhaijaan, and Happy New Year, for example). Any deviation from this equation comes at great risk to the director, producer, and actors. However, it also is not so clear cut.

Despite a widespread belief about skin tone as a marker for morality, Indians still often attach themselves to actors in whom they can see themselves more fully; that is, representation matters. A good example of this is the actress Kajol. Kajol was often acclaimed as being a “dusky Bollywood rebel” (Walia, 2014) actress who at her height of popularity was able not only to be a love interest, but to be a love interest for the biggest stars of the time, something relatively unheard of. However, when she returned after a five-year break to play the lead in Dilwale in 2010, she received harsh criticism because she presented as several shades lighter. Despite her denial of such, she was accused of using lightening creams and perpetuating colorism (ibid).

Figure 8: Ajay Devgn and Kajol at an event for Raju Chacha in 2001. Photo By Bollywood Hungama, CC BY 3.0. Image source.

Figure 9: Kajol promoting Tanhaji in 2019 (cropped). By Bollywood Hungama, CC BY 3.0. Image source.

This anecdote demonstrates both that average Indians do want representation that more closely aligns with their realities, and that Bollywood serves as a role model for many people. Nevertheless, the current system feeds on itself. Social expectations are often created and reinforced in large media productions. As Hall (2006) notes, “the audience is both the ‘source’ and the ‘receiver’ of the [film] message.” The audience learns ideologies from films while supplying the raw material for these ideologies to filmmakers, dictating, through this interaction, the “framework of knowledge” within which filmmakers must operate to succeed (Hall, 2006). Contemporary Bollywood creates an idealized status quo of an upper middle class, light-skinned, upper caste family in order to appeal to the upper middle class Indian and diaspora ideas of themselves. This standard of color and caste becomes reinscribed in the minds of those who watch the films, furthering their belief in their own associations of caste, class, and color. The gentrification of Bollywood that desires respectability, therefore, benefits from encouraging these associations, rather than questioning them. Instead of addressing the systemic issues involved in colorism and looking to deconstruct the values in society that allow such a structure to exist, filmmakers simply point to economics as reasons for perpetuating the system. However, as history has shown time and again, this cycle of suppression and oppression ultimately hurts any creative outlet, especially one that reaches so many different types of people [14].

Gender and Colorism

To return to the opening discussion of the Indian Matchmaker, while colorism continues to oppress all darker people, women bear a larger brunt of the impact of colorism. Colorism builds on gender oppression in the patriarchal society of India (just as it does in America). This means that women are held to higher beauty standards than men, that their usefulness as a mate and mother takes priority over career or other personal ambitions, and they have less say in their life choices compared to their male counterparts [15].

The ideal woman presented in films and encouraged in society is one established in the religious traditions of Hindu culture, especially the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Sita, the main female character of the Ramayana, presents the ideal form of woman as a wife who serves her husband as her god, even if that means refusing friends and family in the process (Dhand 2008). Her whole existence is devoted to her husband and his interests. The wife must always put her husband’s best interests above her own. This heavily Brahmanical tradition of a woman is deeply engrained in the cultural psyche of India. Films, literature, and politicians regularly reinforce the ideal woman in society. While this attitude does not prevent women from achieving successful careers, it absolutely limits their choices and ability to do so. It also creates greater resistance against alternative viewpoints and representations. Indian cultural expectations dictate that women value family over their own careers, adopt socially acceptable behavior around men, and dress conservatively.

While both men and women can be held back by darker skin tones, women face greater educational and economic discrimination (Mishra, 2014; Hunter, 2002; Jones, 2000). Yet it is within the realm of marriage and motherhood that colorism is the most insidious, and therefore the most difficult for women (Vaid, 2009). While the 2011 Indian Census shows 940 women to every 1000 men in the country, women are still held to a higher standard when it comes to marriageability [16]. What this means is that women must prove themselves worthy of men before marrying them. And like in so many other cultures, appearance is a high priority for a “good bride” (Vaid, 2009), as can be seen in Indian Matchmaker mentioned at the beginning of this article. Further, Neha Mishra discusses how in many personal advertisements of parents looking for a bride, “fair” is the most important, more than education, class, or region. If one does not have fair skin, then the other factors must outweigh this negative (Mishra, 2015). These desires stem as much from the family as from the man, because they want the children to be light as well. The fairness desire spans class and region. Mishra describes a law professional who says that “when I go to weddings, if a girl is fairer than the guy I immediately say-lucky guy,” despite being a darker woman herself. She even admits to thinking of those darker than her as dirty. Many of Mishra’s interviewees describe instances of bias and prejudice based on their skin color, yet they also admitted to perpetuating the same colorism. The heightened scrutiny of women happens in Bollywood as well. Women who are dark can play prostitutes, but rarely much else (Arora 2015; Ganapathy 2013; Mishra 2015).

Conclusion

Despite the outcry against Indian Matchmaking and Sima of Mumbai, the Indian matchmaker and central figure of the series, for perpetuating casteist and colorist ideas of beauty, morality, and purity, nevertheless, clearly, she is not an anomaly among the South Asian community. While Bollywood publicly advocates against colorism and has had several films that demonstrate the trauma and damage such attitudes wreak in a person’s life, they simultaneously prioritize light-skinned actors and present them as upper class and upper caste. This disconnect between vocal social progress and active complicity in colorism and casteism stems from the desires of respectability and gentrification that has occurred in Bollywood. Through the lens of gentrification we can see that Bollywood prioritizes an ideal that reflects upper-middle class values in India and the U.S., implicating both India and America in colorism. Because of the pedagogical and ideological space held by films and other popular culture, Bollywood must become active in changing this societal viewpoint, rather than continue to reinforce it. First and foremost, there must be more diversity of representation in the films; not only hiring actors of different color tones, but also having more regional and caste groups represented. They also must avoid stereotyping of lower caste and lower class as being darker skinned. These types of active resistance to ideas of color, caste, and value may seem small, but will start to make large differences in the lives of many Indian women and men.

References

Arora, Gaurav. “11 Accounts Of Racism In Bollywood That Expose The Dark Side Of The Industry.” ScoopWhoop.com. 4 September 2015. Accessed August 24, 2020. https://www.scoopwhoop.com/entertainment/racist-side-of-bollywood/

Begedou, Komi. “Decolonizing the Mind and Fostering Self-Esteem: Fanon and Morrison on Skin Lightening Practices in the African Diaspora.” NAAAS & Affiliates Conference Monographs, Jan. 2014, pp. 1–18.

Bhagat, Sameer. “Adivasi Are Invisible And Unheard In Hindi Movies.” Focus Magazine. September 29, 2018.

Bhattacharya, Stuti. “Priyanka Chopra Owning Her Dusky Skin Abroad Exposes Bollywood's Colourism.” Idiva.com. January 28, 2020.

Brosius, Christiane. India’s Middle Class: New Forms of Urban Leisure, Consumption and Prosperity. Routledge India, 2010.

Chakravarti, Uma. Gendering Caste: Through a Feminist Lens. Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd, 2018.

Vasek, Cheri and Deepsikha Chatterjee. “Costume Artisans of the Indian Film Industry: The Embodiment of Jugaad, Productivity, and Rituality.” The Jugaad Project, 4 Jun. 2020, thejugaadproject.pub/home/costume-artisans-of-the-indian-film-industry-the-embodiment-of-jugaad-productivity-and-rituality [DOA: 11/10/2020]

Chatterji, Rohini. “Bhumi Pednekar's Brownface In 'Bala' Is Infuriating To Watch As A Dark-Skinned Woman.” Huffington Post India. January 19, 2019.

Davis, Richard H. Lives of Indian Images. Princeton University Press, 1997.

Dhand, Arti. Woman as Fire, Woman as Sage: Sexual Ideology in the Mahabharata. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2008.

Dhillon-Jamerson, Komal K. “Euro-Americans Favoring People of Color: Covert Racism and Economies of White Colorism.” American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 62, no. 14, Dec. 2018, pp. 2087–2100.

Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. Penguin Press, 2009.

Dungdung, Gladson. “Hindi feature film MSG-2 sparks outrage over portrayal of Indigenous Peoples.” IC.org. November 6, 2015.

Dutta, Nandita. 2019. F Rated: Being a Woman Filmmaker in India.

Erndl, Kathleen. “Is Shakti Empowering for Women? Reflections on Feminism and the Hindu Goddess.” Is the Goddess a Feminist? The Politics of South Asian Goddesses. Edited by Alf Hiltebeitel and Kathleen Erndl, New York: New York University Press, 2000, pp. 91-103.

Fend, Mechthild. Fleshing out Surfaces: Skin in French Art and Medicine, 1650-1850. Manchester University Press, 2017.

Ganapathy, Nirmala. “Bollywood actress takes on India's complexion bias.” The Straits Times. August, 14, 2013.

Ganti, Tejaswani. Producing Bollywood: Inside the Contemporary Hindi Film Industry. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

Ganti, Tejaswani. “Fair and Lovely: Class, gender and colorism in Bollywood song sequences…” in The Routledge Companion to Cinema & Gender. Edited by Kristin Lené Hole, Dijana Jelača, E. Ann Kaplan, & Patrice Petro. Routledge, 2017.

Hall, Stuart. 2006. “Encoding/Decoding” in Media and Cultural Studies: KeyWorks. Revised ed. KeyWorks in Cultural Studies 2. Edited by, Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner, 163-173. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hinds, Aimee. “Hercules in White: Classical Reception, Art and Myth.” The Jugaad Project, 23 Jun. 2020, thejugaadproject.pub/home/hercules-in-white-classical-reception-art-and-myth [date of access: 9/5/2020]

Hunter, Margaret L. “’If You’re Light You’re Alright’: Light Skin Color as Social Capital for Women of Color.” Gender and Society, vol. 16, no. 2, April, 2002, pp. 175-193.

Jain, Kajri. 2007. Gods in the Bazaar: The Economies of Indian Calendar Art. Durham: Duke University Press.

Jha, Banhi. “Representation of fair-skin beauty and the female consumer.” IOSR Journal fo Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 21, no. 12, ver. 8, December 2016.

Jones, Trina. "Shades of Brown: The Law of Skin Color." Duke Law Journal , vol. 49, no. 6, April 2000, pp. 1487-1558. HeinOnline.

Kellner, Douglas. “Cultural Studies, Multiculturalism, and Media Culture.” Gender, Race and Class in Media. Edited by Gail Dines and Jean M. Humez. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003, pp. 9 – 20.

Lafont, Anne. "How Skin Color Became a Racial Marker: Art Historical Perspectives on Race." Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 51 no. 1, 2017, p. 89-113. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/ecs.2017.0048.

Levinson, Justin D. and Danielle Young. "Different Shades of Bias: Skin Tone, Implicit Racial Bias, and Judgments of Ambiguous Evidence." West Virginia Law Review, vol. 112, no. 2, 2010, p. 307-350. HeinOnline.

Lott, Eric. “Blackface and Blackness: The Minstrel Show in American Culture” Inside the Minstrel Mask: Readings in Nineteenth-Century Blackface Minstrelsy. Edited by Annemarie Bean, James Vernon Hatch, and Brooks McNamara. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1996, pp. 3-32.

Lull, James. “Hegemony.” Media, Communication, Culture: A Global Approach. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

Marriott, McKim and Ronald Inden. “Toward and Ethnosociology of South Asian Caste Systems,” The New Wind: Changing Identities in South Asia, edited by Kenneth David. The Hague: Mountain Publishers, 1977, pp. 227-238.

Matusitz, J., and P. Payano. “The Bollywood in Indian and American Perceptions: A Comparative Analysis.” India Quarterly: A Journal of International Affairs, 67(1), 2011, pp. 65–77.

McIntosh, Peggy. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” Independent School, vol. 49, no. 2, Winter 1990, p. 31. EBSCOhost.

Mishra, Neha. “India and Colorism: The Finer Nuances.” Washington University Global Studies Law Review, vol. 14, no. 4, Global Perspectives on Colorism Symposium Edition 2015.

Mohan, Urmila. Clothing as Devotion in Contemporary Hinduism. Brill Research Perspectives in Religion and the Arts, 2018.

Mukherjee, Sayantan. “Darker Shades of ‘Fairness’ in India: Male Attractiveness and Colorism in Commercials.” Open Linguistics, vol. 6, no. 1, June 2020, pp. 225–248.

Nadeem, Shehzad. “Fair and Anxious: On Mimicry and Skin-Lightening in India.” Social Identities, vol. 20, no. 2/3, Mar. 2014, pp. 224–238.

Nath, Ishani. “The Multiple Dealbreakers of Netflix’s Indian Matchmaking.” The Juggernaut, July 16, 2020.

Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. “Racial Formation.” Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. Routledge. 1994.

Pandey, Geeta. “Fair and Lovely: Can renaming a fairness cream stop colourism?” BBC.com. June 25, 2020.

Pierre, Jemima. The Predicament of Blackness: Postcolonial Ghana and the Politics of Race. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Pinney, Christopher. Photos of the Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India. London: Reaktion Books, 2004.

Reddy, Vanita. “The Nationalization of the Global Indian Woman.” South Asian Popular Culture, vol. 4, no. 1, 2006, pp. 61-85. DOI: 10.1080/14746680600555691

Rehman, Varisha. “Revisiting the Fairness Paradigm in India: Synthesis of Literature and Application of the Self-Concept Theory.” Society and Business Review, vol. 14, no. 1, Feb. 2019, pp. 31–42.

Russell-Cole, Kathy, Midge Wilson, and Ronald Hall. The Color Complex (Revised): The Politics of Skin Color in a New Millennium. 2md ed. Anchor Books, 2013.

Sarkar, Monica. “Why does Bollywood use the offensive practice of brownface in movies?” May 8, 2020. CNN.com.

Shankar P. Ravi, Bishnu Rath Giri, and Subish Palaian. “Fairness Creams in South Asia—A Case of Disease Mongering?” PLoS Med, vol. 3, is. 7, e315, July 25, 2006, p.1187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030315

Shroff, Hemel, Phillippa C. Diedrichs, and Nadia Craddock. “Skin Color, Cultural Capital, and Beauty Products: An Investigation of the Use of Skin Fairness Products in Mumbai, India.” Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 5, Jan. 23, 2018.

Sharma, Arnav Das. “We Need to Talk About Bollywood’s Problem with Making Actors Darker Than They Are: Brownface is not cool, you guys.” Vice.com. June 10, 2019.

Singh, Hira. Recasting Caste: From the Sacred to the Profane. Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd, 2014.

Vaid, Jyotsna. “Fair enough? Color and the commodification of self in Indian matrimonials,” Shades of Difference: Why Skin Color Matters, edited by Evelyn Nakano Glenn. Stanford University Press, 2009.

van den Berghe, Pierre L. and Peter Frost. “Skin color preference, sexual dimorphism and sexual selection: A case of gene culture co‐evolution?,” Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 9, no. 1, 1986, pp. 87-113. DOI: 10.1080/01419870.1986.9993516

Venkataswamy, Sudha. “Transcending Gender: Advertising Fairness Cream for Indian Men.” Media Asia, vol. 40, Jan. 2013, p. 128-138.

Walia, Shelly. “Kajol is no longer the “dusky” Bollywood rebel—and that’s a serious problem.” Quartz India. December 23, 2015.

Walker, Alice. In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. 1st ed., Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983.

Wilkerson, Isabela. “America’s Enduring Caste System.” The New York Times Magazine, July 1, 2020.

Wardhani, Barq, Era Largis, and Vinsensio Dugis. “Colorism, Mimicry, and Beauty Construction in Modern India.” Jurnal Hubungan Internasional, vol. 6, no. 2, 2018, pp. 188-198.

Endnotes

1) The informal process of filmmaking in India has often been critiqued by Westerners as immature or unskilled, especially due to its apparent disorganization and lack of formal processes. For example, it is common for a film script to be written during the filming, rather than before.

2) The term Hinduism is itself a Western abstraction of recent coinage.

3) Walker, Alice. “If the Present Looks Like the Past, What Does the Future Look Like?” in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. 1st ed., Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983, pp290-291. “Colorism – in my definition, prejudicial or preferential treatment of same-race people based solely on their color . . . impedes us.”

4) One additional menace of the heritage of race and colorism is that communities of color are made to feel ashamed about their prioritizing lightness, while simultaneously being conditioned that closeness to whiteness is the gold standard. This insidious double standard furthers generations of feelings of inadequacy brought about in large part by colonialism.

5) For additional information about racism against African immigrants see: Jayawardene, S. M. “Racialized Casteism: Exposing the Relationship Between Race, Caste, and Colorism Through the Experiences of Africana People in India and Sri Lanka” In: Journal of African American Studies, 20(3-4): 323-345; United States: Springer Science + Business Media, 2016.

6) He throws out his lightening cream once he has fully committed to the love interest, a woman who society considers of questionable repute. While this could be read as an indication that he has rejected social norms, the fact that he continues to emphasize her status as an outcast, presents the act more as an indication that he doesn’t need it because of the woman he chose. Further, the scene happens so quickly that anyone not paying close attention would easily miss the quick action.

7) Somewhat surprisingly, discussions surrounding difficulty of filming darker skin does not arise in Bollywood the way it does in Hollywood. This is likely, at least in part, due to the greater color saturation most Bollywood films use as standard levels. However, for reference to some helpful discussions about film lighting and camerawork on darker skin tones, see:

a. Aguirre, Abby. “Moonlight’s Cinematographer on Filming the Most Exquisite Movie of the Year.” Vogue.com. December 20, 2016.

b. Harding, Xavier. “Keeping ‘Insecure’ lit: HBO cinematographer Ava Berkofsky on properly lighting black faces.” Mic.com. September 6, 2017.

c. Latif, Nadia. “It’s lit! How film finally learned to light black skin.” The Guardian. September 21, 2017.

d. Martin, Cybel. “The Art of Lighting Dark Skin for Film and HD.” Shadow and Act. April 20 2017.

e. “Ava Duvernay on lighting the black body and how black characters look in dark rooms.” Youtube, April 23, 2015.

8) Based on the 2011 Indian Census: https://minorityrights.org/minorities/adivasis-2/

9) The 2015 film, MSG 2 the Messenger received criticism about its representation of the Adivasi as devils who needed to be transformed into humans. Prem Mardi, a resident of Ghatshila, Jharkhand, sued for the film to be banned and for damages against the director and producer citing that the film promoted hatred and ethnic discord against the Adivasis. In a startling response, the Delhi High Court denied the suit claiming that Adivasi was not the same as a Scheduled Tribe, arguing, “The reference in the film to Adivasis is not found to be relatable in any manner to Scheduled Tribes. There is thus no merit in the petition. Dismissed.” Not only does this completely ignore the colloquial use of the term, it also ignores previous Supreme Court rulings using the terms interchangeably (Dungdung 2015).

10) Despite not following the religious ideas of caste, Muslims in South Asia, especially India, still work within the caste system. However, the focus of caste works more as a social grouping rather than the same religious ideas. Caste among Muslims in South Asia is more complicated than the scope of this essay, but some resources to look into it include:

a. Caste and Social Stratification among the Muslims. Edited by Imtiaz Ahmad. Monohar Book Service, Delhi, 1973.

b. Syed Ali. “Collective and Elective Ethnicity: Caste among Urban Muslims in India.” Sociological Forum, vol. 17, no. 4, Dec. 2002, pp. 593–620.

c. Bashir, Kamran, and Margot Wilson. “Unequal among Equals: Lessons from Discourses on ‘Dalit Muslims’ in Modern India.” Social Identities, vol. 23, no. 5, Sept. 2017, pp. 631–646.

d. Usman, Ahmed. “A Comparison of Hindu and Muslim Caste System in Sub-Continent.” South Asian Studies (1026-678X), vol. 32, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 91–98.

11) This video, “Meet the real Rancho of 3 Idiots, Sonam Wangchuk, who inspired Aamir Khan’s role” provides more in-depth information about the work of the real engineer who changed expectations of education.

12) Akshay Kumar’s films: Toilet: Ek Prem Katha, Pad Man, and Mission Mangal deal with issues of rural India and gender discrimination. Ayushmann Khurrana is outspoken about taking on taboo subjects in his films to destigmatize them. His films include Vicky Donor, Dum Laga Ke Haisha, Shubh Mangal Saavdhan, Badhaai Ho, Bala, and Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan. Aamir Khan’s work includes pointing out dyslexia, education issues (3 Idiots), religious zealotry (PK), and rural farming suicides (Peepli Live).

13) It should also be noted that many of these films also perpetuate a strong Hindutva or Hindu-leaning nationalism, making their films more insidious than simply a sanitized social ill (see Rao, Pallavi. “Soch Aur Shauch: Reading Brahminism and patriarchy in Toilet: Ek Prem Katha” Studies in South Asian Film and Media, vol. 9, no. 2, January 2019, pp. 79-96.)

14) By removing diversity of experience, Bollywood may become even more devoid of original films, potentially pushing audiences to other sources. In the past decade Bollywood has started following Hollywood by making sequels and remakes of older films. At the same time, streaming sites like Netflix and Amazon Prime have provided opportunities for those who struggle in traditional Bollywood spaces.

15) In the documentary A Suitable Girl, Dipti Admane, the one person who seemed genuinely happy to marry her chosen partner, cries at the prospect of leaving home after marriage. She complains that only women have to suffer this loss, since women traditionally move into their husband’s family’s house after marriage. Amid her tears, she affirms that she cannot say if it is unfair or not, it is just the way it is.

16) India Census Bureau (2011). “5.2 Sex Ratio – India and States” in Gender Composition. Retrieved from: https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/data_files/mp/06Gender%20Composition.pdf