Food for Thought: The Contributions of 'Matière à Penser' to the Study of Material Culture

Citation: Warnier, Jean-Pierre. “Food for Thought: The Contributions of 'Matière à Penser' to the Study of Material Culture.” First published in Material Religions Blog, 24 Sept. 2014. Revised and republished in The Jugaad Project, 11 Jul. 2019. Updated 22 Jan. 2021. thejugaadproject.pub/home/food-for-thought [date of access]

VIRTUAL BOOK RELEASE FOR ‘THE MATERIAL SUBJECT’, JAN. 12, 2021

The Material Subject emphasises how bodily and material cultures combine to make and transform subjects dynamically. The book is based on the French Matière à Penser (MaP) school of thought, which draws upon the ideas of Mauss, Schilder, Foucault and Bourdieu, among others, to enhance the anthropological study of embodiment, practices, techniques, materiality and power.

CONTACTS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MAP NETWORK

United Kingdom Myriem Naji

Norway Geoffrey Gowlland

Switzerland Hervé Munz

France Céline Rosselin-Bareille

United States Urmila Mohan

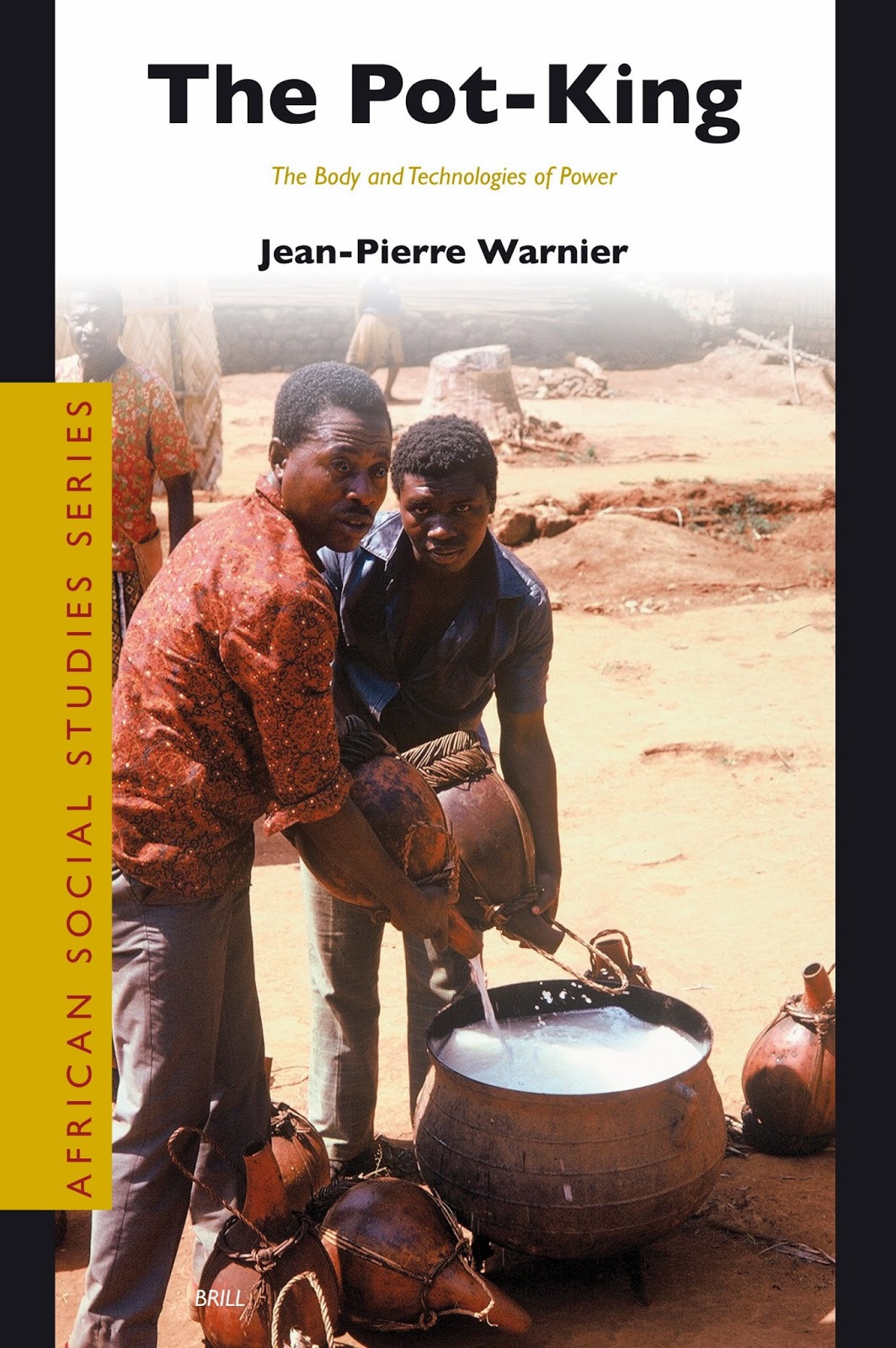

Editor’s note: As one of the founding members of the ‘MaP’ (Matière à Penser) working group and author of “The Pot King” Jean-Pierre Warnier’s research has been devoted to the study of bodily and material culture. He authored this brief description below of the main ideas of the group, belatedly turned into an informal network.

First, it brings together the study of bodily techniques and material culture, drawing on the notion of the Körperschema defined by Paul Schilder in 1935. Schilder insisted on the fact that in motion, perception and emotions, the human body does not end with its coetaneous envelope but extends beyond it. The lady’s hat and the blind man’s cane are part and parcel of their bodily schema and bodily techniques. This Schilderean concept of ‘bodily schema’ or image of the body was picked up by Merleau-Ponty as a key element in his phenomenology of perception. It is fully validated by contemporary neuro-cognitive sciences. Bodily techniques and material culture are so tightly knit together that one should not separate them. One should talk of bodily-and-material-culture hyphenated together. Motion is an essential component of the approach. In that perspective, bodily-and-material-culture is knit together on the move. Accordingly, it draws on ‘praxeology’ – a term coined at the end of the 19th c. by Espinas, and developed by Pierre Parlebas as the study of bodily conducts. Marcel Mauss with his techniques of the body and his notion of techniques as traditional and efficacious action is also a major reference. Bodies and material things are analyzed not for what they mean in a system of coded communication or connotation but for what they do to the subject or achieve in a social system of agency and efficacy.

The second key element in the MaP approach to bodily-and-material-culture is the consideration of the subject as being and having a (material) body. Regarding the question of the subject, the theoretical input comes from Michel Foucault, Michel de Certeau, Slavoj Zizek and other philosophers who have disqualified the Cartesian and neo-Kantian subject defined by the cogito. The notion they develop takes into account the development of the social and human sciences in the 20th century. The subject takes him/herself as the object of his/her own actions and at the same time is subjected to a vast array of actions exercised by other subjects and, in the end, by a sovereignty. It is divided up between being and having a body, between self and others, between autonomy and heteronomy. This goes against the notion of the ‘individual’ as developed by most socio-anthropological theory.

The notion of a subject helps integrate the body as a subject/object; the material things and substances geared to the bodily schema; the seven sensory canals (or more) that gear the body to material culture (including kinesthesia and the vestibular sense of balance and movement); the psychic drive that keeps the subject on the move; the society to which it belongs etc. This theoretical took kit may apply to the technologies of the subject, to the technologies of power, to the production of religious subjects, city dwellers, consumers, to sports, work, armed violence, etc., always combining an interest in the technologies of the subject, its body, perception and materialities.

The MaP group was formed at University Paris-Descartes in the mid-1990s by a few staff members, students, and doctoral candidates but also “town” as opposed to “gown” people – altogether a turnover involving several dozens of persons at a turn. A number of doctoral dissertations were produced by implementing its theoretical framework by Céline Rosselin-Bareille, Marie-Pierre Julien, Agnès Jeanjean, Mélanie Roustan, and François Hoarau. Around 2005, the members of the group were scattered by their various assignments and the group turned into an informal network active in publishing and doing research on many different topics that justified a declension of its name as “Matière à Politique”, “Matière à Religion”, etc. In the meantime, it had established contacts and working relationships with other units working on material culture at University College London, University Aix-Marseille, University of Oslo, Musée du Quai Branly, etc.

Since ‘The Jugaad Project’ deals with religion, let me address this in specific. There is no religious practice in the world that does not aim to capture the subjectivities of its practitioners through sensory-motor practices grounded in specific material cultures. The religious adept fasts, feasts, consumes psychotropic substances, sings, plays instruments, goes on pilgrimage, and adheres to practices such as (in the case of the Islamic Hajj) stoning the stele of Satan. Sensorimotor praxeology and the fine study of material cultures in action thus offers a privileged tool for studying in an original way the religious fact and its articulation with politics. Indeed, one of the limitations of religious studies is that by focusing on representations, symbolism, beliefs—in short, everything that happens "in the head"—it is hardly an ethnography of practice and fails to account for the mechanisms of assent, adherence, and impact of practice on subjectivities. Religious anthropology takes into account only half of the brain: that of verbalized knowledge. The other half of the brain, that of procedural knowledge that is poorly verbalized and preconscious, is equally important. The praxeological paradigm poses theoretical questions about the relationship between body and language, procedural knowledge and verbalised knowledge that are of the highest interest, insofar as one cannot postulate either independence or perfect superposition between these two types of knowledge. In the gaps and contradictions between the verbalized and procedural, there is a mine of data and perspectives to explore on the mechanisms of adhesion, control, even manipulation, of religious and political subjectivities.

Most, but not all, publications by and on the MaP network are in French and have not been translated. Some have been published in English. The list of MaP publications (and those of its associates) includes:

Bayart, Jean-François & Warnier, Jean-Pierre (2004). Matière à Politique. Le Pouvoir, les Corps et les Choses. Paris ; CERI-Karthala, Coll. Recherches internationales.

Diasio, Nicoletta and Marie-Pierre Julien (ed.) (2019), Family Food Practices, Constraints, Adjustments and Innovations, Bruxelles, Peter Lang.

Diasio, Nicoletta, Julien, Marie-Pierre & Lacaze, Gaelle (2009). « Déjeuner en Ville » in Diasio, Nicoletta, Hubert, Annie et Pardo, Véronique, Alimentations Adolescentes en France, OCHA, Paris, Les cahiers de l’Ocha n°14.

Douny, Laurence (2014). Living in a Landscape of Scarcity: Materiality and Cosmology in West Africa. Walnut Creek, CA; Left Coast Press.

Gowlland, Geoffrey (2016). “Materials, the Nation and the Self: Division of Labor in a Taiwanese Craft.” in Clare Wilkinson-Weber and Alicia Ory DeNicola (eds.) Critical Craft: Technology, Globalization, and Capitalism. London: Bloomsbury.

_____ (2011). ‘The ‘Matière à Penser’ Approach to Material Culture: Objects, Subjects and the Materiality of the Self’ Journal of Material Culture Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 337-343.

Grison, Benoit & Céline Rosselin (2006). « Schéma corporel » in Bernard Andrieu (ed.) Dictionnaire du Corps en Sciences Humaines et Sociales, Paris, Ed. du CNRS, pp. 457-458.

Hilpron, Michael (2011). « De « faire du judo » à « faire judo » Approche ethnographique d’une pratique de haut-niveau par la culture matérielle »,Thèse de Doctorat sous les directions de Bronislaw Kapitaniak et Céline Rosselin, Université d'Orléans.

Hilpron, Michael & Céline Rosselin (2015). « Culture matérielle et sport », in Vocabulaire International de Philosophie du Sport, vol 1 : Les origines, Bernard Andrieu (ed.) Paris, L’Harmattan, coll. Mouvements des Savoirs, pp. 363-367.

Jamard, Jean-Luc, (2002). « Au cœur du sujet : le corps en objets ? » Techniques & Cultures, n° 39.

Julien, Marie-Pierre & Céline Rosselin (2012). « Manger ou ne pas manger, quelle est l’émotion ? Corps, culture matérielle et émotions en situation », in Le Corps, n°10, N. Diasio et V. Vinel « Corps, matière et affects », Paris ; CNRS.

_____ (2009). Le sujet contre les objets… tout contre. Ethnographies de cultures matérielles. Paris ; CTHS.

_____ (2006). « Culture matérielle incorporée et processus d’identification. Navigateurs de compétition et croisiéristes ‘bord à bord’ » in Stéphanie Tabois (ed.) Corps en Société, ICoTEM, Poitiers, de la Maison de l’homme et de la société.

_____(2005). La Culture matérielle. Paris ; La Découverte, Coll. « Repères ».

_____(2005). “Culture matérielle et construction des sujets” In Marie-Pierre Julien and Céline Rosselin eds. La Culture matérielle. Paris: La Découverte. pp. 65-90. (English Translation)

_____(2002). « C’est en laquant que l’on devient laqueur. De l’efficacité du geste à l’action de soi sur soi chez les Chinois du Faubourg Saint-Antoine », Techniques & Cultures, n° 40, pp. 107-124.

Julien, Marie-Pierre and Ingrid Voléry (2019). « Corps, normes, temps » M.-P. Julien et I. Voléry (ed.), Mesurer les corps pour normer les temps de vie, Recherches sociologiques & anthropologiques, 2019, n°50-1, Bruxelles. https://doi.org/10.4000/rsa.304

Julien, Marie-Pierre, Poirée Julie, Rosselin, Céline, Roustan, Mélanie & Warnier, Jean-Pierre (2002). « Chantier ouvert au public », Techniques & Cultures, n° 40, pp. 185-192.

Julien, Marie-Pierre, Poirée, Julie & Rosselin, Céline (2006). « Sujet », in Bernard Andrieu (ed.) Dictionnaire du Corps, Paris ; Editions du CNRS.

Julien, Marie-Pierre, Rosselin, Céline & Warnier Jean-Pierre (2006). « Le Corps : Matière à Décrire », in Corps, revue interdisciplinaire, n°1, Paris ; Dilecta.

Julien, Marie-Pierre & Warnier, Jean-Pierre (1999). Approches de la Culture Matérielle. Corps à Corps Avec L’objet. Paris ; L’Harmattan, Connaissances des hommes.

Julien, Marie-Pierre, O. Wathelet and L. Dupré (2018). « Conserver : déjouer le temps et l’espace, (re)prendre du pouvoir », Techniques et culture, n° 69, Paris, ed. de l’EHESS, 10-22.

Julien, M.-P., O. Wathelet and L. Dupré (ed.) (2018). Le temps des aliments : quelle société de conservation? Techniques et Cultures , n° 69, Paris, ed. de l’EHESS.

Julien, Marie-Pierre (2021). “Clothing choices and questioning the incorporation of habitus”, in U. Mohan and L. Douny (ed.) The Material Subject: Rethinking Subjects Through Objects and Praxis, London and New York, Routledge, pp. 61-74.

_____(2019). « Are Eating-related Cycles in Contemporary French Families ? » in M.-P. Julien and N. Diasio (eds.), Contemporary Family Food Practices, Constraints, Adjustments and Innovations, Bruxelles, Peter Lang, pp. 135-161.

_____(2019), « Introduction-food practices innovations with constraints » in M.-P. Julien and N. Diasio (eds.), Contemporary Family Food Practices, Constraints, Adjustments and Innovations, Bruxelles, Peter Lang, pp. 9-26.

_____(2018). « Food provisioning - from supermarket to producer: Understanding the articulation of different suppliers », Review of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Studies RAFES, 2018, 99-1, Springer, 1-14. DOI: 10.1007/s41130-018-0070-0

_____(2018) (ed.), Food provisioning, Review of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Studies RAFES, 2018, 99-1, Springer.

_____(2017). « La chambre des 9-13 ans : Un espace ouvert aux circulations des sujets et des objets », Diasio N., Vinel V. (ed.), Corps et préadolescence : entre intime, privé et public, Rennes, PUR, pp. 79-97.

_____(2015). « Quand poussent les poils des garçons », Ethnologie Française, Paris, PUF, 2015, Tome XLV, 677-684.

_____(2015). « Sujet, subjectivation, subjectivité et sciences sociales », Cahier n°4, Nantes, Lestamp, 87-106.

_____(2014). « Choisir ses Vêtements et Ouvrir la Boite Noire des Habitus » in Nicoletta Diasio et Virginie Vinel « Sortir de L’enfance. La ‘préadolescence’ : Une Nouvelle Catégorie D’âge ? », Revue des sciences sociales n°51, Strasbourg.

_____(2014). « Techniques Corporelles, Culture Matérielle et Identifications en Situations » in Marc Durand, Denis Hauw et Germain Poizat Apprendre les Techniques Corporelles, PUF.

_____(2014). « Circulation des Objets et Pratiques de Soin de Soi Chez les Enfants de 9 à 13 ans. Au Croisement des Identifications : La Construction du Genre » in Sabrina Sinigaglia-Amado, Enfance et Genre. Modalités et effets de la socialisation sexuée, Nancy ; PUN.

_____(2013). « Des Situations Commensales Adolescentes : Entre Pluralité Normative, Conflits et Construction de Soi » in Anne Lhuissier, Aurélie Maurice & Thomas Depecker, Mesures et Réformes des Pratiques Alimentaires, PUR.

_____ (2006). « Techniques du corps » in Bernard Andrieu, Dictionnaire du Corps, Paris, Editions du CNRS.

Lalo, E. and C. Rosselin-Bareille, forthcoming, “Sens-dessus-dessous. Apprentissages sensoriels et

environnements hostiles chez les scaphandriers travaux publics”, in V. Battesti and J. Candau (dir.), Apprendre des sens, apprendre par les sens, Paris, Editions Petra.

Manzon, Agnès Kedzierska (2014a). Chasseurs Mandingues: Violence, Pouvoir et Religion en Afrique de l'Ouest. Paris: Karthala.

_____ (2014b). "Corps et objets forts: le 'fétichisme comme ascèse", Corps (CNRS éditions), no. 12, pp. 211-220.

Mélo, D. and C. Rosselin-Bareille (2019) ““Quoi faire“ en attendant l’intervention ? Le professionnalisme pompier à l’épreuve de l’attente », Varia, Socio-Anthropologie, 40, pp. 231-246.

Mohan, Urmila (2019) “Clothing as Devotion in Contemporary Hinduism”. Brill Research Perspectives in Religion and the Arts, 2(4):1-82.

_____ (2016). “From Prayer Beads to the Mechanical Counter: The Negotiation of Chanting Practices Within a Hindu Group”, Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions, 174:191-212.

Mohan, Urmila and Laurence Douny eds. (2021). The Material Subject: Rethinking Bodies and Objects in Motion. London: Routledge.

Mohan, Urmila and Jean-Pierre Warnier (2017). “Editorial: Marching the Devotional Subject”, Journal of Material Culture, Special Issue on Religious Subjectivation, 22(4): 369-384.

Moricot, C. and C. Rosselin-Bareille, forthcoming, “Quand des hommes respirent sous l’eau et volent dans l’air: entre cultures matérielles et incapacités naturelles”, S. Renesson and A. Vallard (dir.) “Abîmes, abysses, exo-mondes. Explorations en milieux-limites et techniques de confinement”, Techniques & Culture, 75.

Munz, Hervé (2016). La transmission en jeu: apprendre, pratiquer, patrimonialiser l'horlogerie en Suisse. Neuchâtel: Ed. Alphil.

_____ 2015. « La captation patrimoniale des savoir-faire horlogers au risque de leur transmission », Ethnologies, no 36/1-2, Le patrimoine culturel immatériel. Québec: Presses de l'Université Laval.

_____ 2012. « L' "ébauche" du geste. Apprentissage horloger et (trans)formation des corps », Tsanta 17, Société Suisse d'Ethnologie, Zurich: Seismo Verlag, pp. 168-172.

Naji, Myriem and Laurence Douny (2009). ‘Editorial: Special Issue on “Making” and “Doing” the Material World’ Journal of Material Culture, 14: 411-432.

Nourrit, D. and C. Rosselin-Bareille (2017) “Incorporer des objets : Apprendre, se transformer, devenir expert”, C. Rosselin-Bareille (ed.), Matières à former, Socio-Anthropologie, 35, pp. 93-110.

Rosselin, Céline, Elodie Lalo & Déborah Nourrit (2015). “Prendre, Apprendre et Comprendre. Mains et matières travaillées chez les scaphandriers”, Revue ethnographiques.org La part de la Main, no. 31.

Rosselin-Bareille C. ed. (2017). Matières à former. Socio-Anthropologie, no. 35.

Rosselin-Bareille C., forthcoming « De l’acte ou l’oubli du Sujet-et-des-objets-dans-unenvironnement», in M.-A Dujarier, A. Gillet et P. Lénel (ed.), L’activité en théorie 2, Toulouse, Octarès.

Rosselin-Bareille, C. (2021). “Making do and wanting: The Professional Diver’s predicament”, in

U. Mohan and L. Douny (eds.), The Material Subject: Rethinking Bodies And Objects in

Motion, London, Routledge.

_____ (2019). “Pas envie d’être enterré vivant !“. De l’hostilité chez les scaphandriers Travaux Publics”, M. Peyrière and E. Ribert (ed.) Vivants sous terre, Communications, no. 105, pp. 119-129.

_____ (2019). “Tourner“. Corps au travail et pénibilité chez les scaphandriers travaux publics”, L. Jacquot and I. Volery (ed.) Corps au travail, corps travaillés, Nouvelle Revue du Travail, no. 14, pp. 23-38.

_____ (2017). “Matières à Former-Conformer-Transformer”, C. Rosselin-Bareille (ed.) Matières à former, Socio-Anthropologie, no. 35, pp. 9-22.

_____ (2015). « Scaphandriers non autonomes à l’épreuve des matières. Culture matérielle, sensations et culture motrice », in Mary Schirrer (ed.) S’immerger en apnée : cultures motrices et symboliques aquatiques, Paris, L’Harmattan, coll. Mouvements des savoirs, pp. 105-120.

_____ (2014a). « "Etre dedans": La Question de L'immersion Chez les Scaphandriers Non Autonomes. Culture Matérielle, Sensations et Culture Motrice », in Mary Schirrer et Bernard Andrieu (eds.) S’immerger en Apnée : Cultures Motrices et Symboliques Aquatiques. Paris ; L’Harmattan, coll. Mouvements des savoirs.

_____ (2014b). « Quand des Cultures Matérielles Construisent des cultures Motrices : L’exemple des Scaphandriers Non Autonomes » in Bernard Andrieu, Betty Lefevre et Olivier Sirost (éds.), Cultures Corporelles. Héritages et Pratiques. Nancy ; PUN.

_____ (2006). « Incorporation d’objets », in Bernard Andrieu (ed.) Dictionnaire du Corps en Sciences Humaines et Sociales, Paris, Ed. du CNRS, pp. 259-260.

Roustan, Mélanie (2011). « Fumer Tue et Fumer Pue : Métamorphoses Sociales et Culturelles du Tabac et de sa Combustion » in Pierre Lieutagi et Danielle Musset (dir.) Les Plantes et le Feu, C’est-à-dire Éditions, coll. « Un territoire et des hommes ».

_____ (2009). “From Embodied Ethnography to the Anthropology of Material Culture: Gaming in the Field”, in Phillip Vannini (ed.) Material Culture and Technology in Everyday Life: Ethnographic Approaches. New York; Peter Lang Publishing, pp. 89-100.

______ (2007). Sous L’emprise des Objets ? Culture Matérielle et Autonomie. Paris ; L’Harmattan, coll. « Logiques sociales ».

_____ (2003, dir.) La Pratique du Jeu Vidéo : Réalité ou Virtualité ?, Paris ; L’Harmattan, coll. « Dossiers Sciences Humaines et Sociales ».

Salpeteur, Matthieu & Jean-Pierre Warnier (2013). « Looking for the Effects of Bodily Organs and Substances Through Vernacular Public Autopsy in Cameroon » Critical African Studies, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 153-174.

Voléry, I. and M.-P. Julien (ed.) (2020)., From Measuring Rods to DNA Sequencing: Assessing the Human, New York et Singapore, Palgrave-Springer, coll. Health, Technology and Society.

Voléry, I. and M.-P. Julien (2020). “The geopolitics of bone: political and medical controversies over the measurement of bone age in unaccompanied foreign minors” in I. Voléry and M.-P. Julien (ed.), From Measuring Rods to DNA Sequencing: Assessing the Human, New York et Singapore, Palgrave-Springer, coll. Health, Technology and Society, pp. 175-203.

Voléry, I. and M.-P. Julien (ed.) (2019). “Mesurer les corps pour normer les temps de vie”, Recherches sociologiques & anthropologiques, n°50-1, Bruxelles.

Warnier Jean-Pierre and Céline Rosselin (1996). Authentifier la Marchandise, Anthropologie Critique de la Consommation de Masse. Paris ; L’Harmattan, Dossiers.

Warnier, Jean-Pierre, (2011). “Bodily/material Culture and the Fighter’s Subjectivity”, Journal of Material Culture, Vol. 16, No. 4: pp. 359-375.

_____(2010). “Royal Branding and the Techniques of the Body, the Self, and Power in West Cameroon”, in Andrew Bevan and David Wengrow (eds.) Cultures and Commodity Branding. Walnut Creek (CA) ; Leftcoast Press, 2010, pp. 155-166 (UCL Institute of Archaeology Publications).

_____(2009). “Technology as Efficacious Action on Objects . . . and Subjects” Journal of Material Culture, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 459-470.

_____(2007). The Pot-king: The Body and Technologies of Power. Leiden; Brill.

_____(2005). “Inside and Outside. Surfaces and Containers”. In Chris Tilley, et al. (eds.), Handbook of Material Culture, London, Sage, pp. 186-195.

_____(2001). “A Praxeological Approach to Subjectivation in a Material World”, Journal of Material Culture, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 5-24.

_____(1999). Construire la Culture Matérielle. L’homme qui Pensait Avec ses Doigts. Paris; PUF.

_____(1994). Le Paradoxe de la Marchandise Authentique. L’objet de Consommation et L’imaginaire de L’authenticité. Paris ; L’Harmattan, Dossiers.

References

Certeau, Michel de (1986). Heterologies: Discourse on the Other. Minneapolis, MN; Minnesota University Press.

Espinas, Alfred V. (1897). Les Origines de la Technologie. Paris; Félix Alcan.

Foucault, Michel (1988). ‘Technologies of the Self’ in Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patrick Hutton (eds), Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, pp 16-49.

Foucault, Michel (1973). Ceci n'est pas une pipe. Ed. Fata Morgana. Illustrations by René Magritte.

Mauss, Marcel (1936/2006). ‘Techniques of the Body (1936)’ In Nathan Schlanger (ed) Techniques, Technology and Civilisation. New York; Berghahn Book, pp 77-95.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception. Paris; Gallimard.

Parlebas, Pierre (1999). Jeux, Sports et Sociétés. Lexique de Praxéologie Motrice. Paris; INSEP.

Schilder, Paul (1935/1950). The Image and Appearance of the Human Body. Oxon; Routledge.

Zizek, Slavoj (2000). The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology. London, New York; Verso.