Gazing to Africa: A Conversation with Art and Ethnology at the Museum

Abstract: This short essay explores how museum displays have traditionally shaped static public knowledge about Africa and Africans. Impressions from one spectator’s experience of the exhibit Beyond Compare: Art from the Bode Museum (Berlin) will serve as a springboard to reimagine how art and ethnological collections can dismantle the ideologies of cultural domination embedded in these items’ preservation and presentation to the public. The discussion is inspired by current mainstream conversations in North America and Europe about the kinds of detrimental impacts and exclusion their national symbols and institutions promote in an increasingly converging multicultural world.

Citation: Antohin, Alexandra. “Gazing to Africa: A Conversation with Art and Ethnology at the Museum.” The Jugaad Project, 7 Sept. 2020, thejugaadproject.pub/gazing-to-africa [date of access]

Two small figures in bronze and copper are positioned side-by-side in “the Basilica”, a gallery room with vaulted ceilings designed to look and feel like the central hall of a Baroque era cathedral. To the right: Goddess Irhevbu (or Princess Edeleyo, the caption offers), speculated to originate from a ceremonial altar in the Kingdom of Benin and produced in the 16th or 17th century. To the left: a Renaissance-styled cherub holding a tambourine, created by 15th century sculptor Donatello and originally from a Catholic baptismal font in central Italy.

Figure 1. Putto with Tambourine, Donatello, Tuscany (Italy), 1428-29, bronze; Statue of the Goddess Irhevbu or of Princess Edeleyo, Kingdom of Benin (Nigeria), 16th or 17th century, copper (l-r). Photo by author. Berlin, Germany 2019.

The staging of a glass case in the entrance of this monumental space, with few objects to distract attention, effectively creates a figurative spotlight on a particular method of juxtaposition. This visual arrangement prompts an observer, without commentary or contextual cues, to stand and compare these two works’ aesthetic qualities: the Goddess/Princess’s youth and beauty, the lithe movements of the winged musician. For the curators of the exhibit Beyond Compare: African Art from the Bode Museum (Berlin) this arrangement is part of an experiment to create dialogues between African and European works of art. The crux of their experiment is to engender a freedom for the spectator to build connections using their own aesthetic instincts as well as to confront the legacies of harmful enculturation that has kept these items separate. The staging of the two figures is provocative because expressive culture from the African continent has historically been classified and presented as ethnology, not art.

This essay’s central objective is to consider the balancing act between appreciating “art for art’s sake” and locating and disentangling the biased categories that shape how African art is valued and judged. I phenomenologically portray the experience of walking into the Basilica hall because I felt a specific intention of the curators: to trust the spectator to create values and meanings divorced from the racist legacies of ethnological sciences, which arranged societies on a sliding scale of cultural achievement. This was refreshing and inspired and I sincerely hope that similar experiments will be more commonplace. The reality, though, is that such exhibits have historically been rare. For expressive culture outside of European cultural groups, filling in the historical gaps that accompany these exhibit items is quickly becoming a requirement. The publicity around the provenance and the illegal acquisitions of the “Benin Bronzes” in European museum collections serves as one high-profile example of the debates at the forefront of decolonization movements and initiatives in the cultural sector. This discussion will approach these debates from another angle by examining how contemporary ethnographic practices and ideas might push the reconfiguration of the traditional museum. I refer to the Beyond Compare exhibit not to review its merits and critique its arguments – personally I came away with the impression that the exhibit successfully achieved a new path for the complicated and essential work of understanding the disturbing legacies of museums and their practices of cultural comparison. Instead, I refer to the exhibit as part of a broader trend towards generating ethically-charged frameworks for contemporary exhibit work.

Visiting this exhibit in October 2019, I was drawn as an educator who teaches on topics of African studies but struggles to trust museums to present Africa and Africans fairly. As I explain to students, the distorted registers of value in these cultural institutions have historically served a political purpose for societies in Europe and North America. The derogatory classification of African art and artists reflected evolutionary thinking popular in the 19th century that proposed to treat non-Europeans as underdeveloped humans, its material culture presented as evidence to support this worldview (i.e. Morgan’s multi-tiered scale of savagery, barbarism, and civilization is the classic example from this era). Through this ideological frame, the context of museums, and the grammar of their comparative method, take on added political importance and utility. The more foreign objects and ideas are to each other, the more firm the relational contrast becomes. These ideas coincided with several related scholastic developments. The establishment of ethnology [1], “the study of both the cultural differences and the features which identify the common humanity of the world’s people” (Barnard 2000:2), tied concurrently with colonial presence and exploitation, which initiated the archives of private collectors and public institutions. These items are what compose the repositories of many museums today.

Magnifying this legacy of racial and ethnic comparison makes the arrangement of the Benin and Italian renaissance statues jarring for spectators conditioned to encounter creations and artifacts in distinct cultural or regional zones. It is instructive to juxtapose the visual and sensory presentation of the Goddess Irhevbu and putto statue as described earlier (see Figure 1) with its accompanying display text. The two figures’ functional properties appear to be neatly parallel: the two items were created for contexts of worship and spiritual cosmology. However, the captions narrates how their journeys to the museum took divergent paths and radically reconfigured their cultural value. The putto figure by Donatello has been a prized treasure of European art and has elevated the prestige of other items in the museum collection (Rowley 2015). The Benin statue faced a different fate.

“After 1900, despite their unquestionable importance in their original context, the two objects were interpreted differently in Berlin museum collections. Celebrated as a key work by the Renaissance mater Donatello, the putto had a prominent place in the new Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (now Bode Museum). The Benin figure, by contrast was more difficult to assimilate. Although in 1897 many masterpieces from Benin were taken by British troops who attacked the Kingdom, their artistic value was disputed. Such works often were seen as “primitive.” Some commentators saw them as artistic and named their creators “native artists”, others thought that the works left a barbaric impression” (Bode Museum, Statue of the Goddess Irhevbu or of Princess Edeleyo, 2017, Beyond Compare: Art from Africa in the Bode Museum: Germany).

The caption’s text effectively underscores that these two items were not treated equally by European cultural institutions and their audiences and that what the present-day spectator is witnessing is a break from established trends, at least for the Bode.

Providing historical context is important and necessary for understanding the colonial and imperialist ideas that have shaped how museums are arranged. As I reflected on my phenomenological reception of the figures and the textual annotation presented in their captions, I wondered whether these arrangements dissolved or reintroduced the bias that marked African items as ethnological specimens and not art. Leveling the plane of comparison "corrects" a racist agenda, but also implicitly signals that the Benin figure is being rescued and afforded an improved status by its placement next to the famous Donatello through this act of political rectification. Perhaps this interpretation (mine exclusively) exists because of the lingering legacies of how cultural institutions present ethnological arguments. Another display further into the narrative arc of the exhibit (as opposed to Figure 1 which serves an introductory purpose) [2], juxtaposes two items from the fifteenth and sixteenth century and present an exercise that offers more neutral frames of reference for the general spectator. Portrait Heads (Figure 2) positions two sculptures of human heads -- John the Baptist from Judea and an ancestor king (oba) from the Kingdom of Benin -- as the common element of comparison. The accompanying captions propose several themes for consideration, such as portraying death as a precise moment in time (i.e. the beheading of John the Baptist as an important event in Christian Biblical history). The oba statue communicates death as an eternal quality of authority. The display text explains how oba figures were sculpted to transcend the representation of a singular historical figure and also utilizes the caption to prompt contrasts in ideas between the European and African expressive culture (see Figure 3). This side-by-side arrangement serves as one example of how visual, experiential and textual curation guides the spectator to appreciate the two items as commonly human and trusts the viewer to establish threads of connecting value.

Figure 2. Head of John the Baptist on a Charger (Belgium), ca. 1430, oak; Head of an oba (deceased king), Kingdom of Benin (Nigeria), 16th century, bronze (l-r). Photo by author. Berlin, Germany 2019.

Figure 3. Captions for “Head of an oba” and “Head of John the Baptist on a Charger” (l-r). Photo by author. Berlin, Germany 2019.

Merging the collections, specifically art and ethnological, into this particular dialogue ignites important correctives, such as examining how “Institutional arrangements, and the categories institutions devise, reflect and reinforce worldviews and ontologies” (Chapuis, Fine, and Ivanov 2017: 12-13). Speculating here, but the curatorial vision produced by Beyond Compare emanates from the problematic histories of ethnological collections and the well-defined debates in German sciences and humanities regarding scientific racism, ethnology and anthropology.[3] Following the lead of exhibits such as Beyond Compare, inserting an ethnological consciousness to art collections holds the potential to induce essential revisions to the spectator experience for a more global audience. As a fast demonstration, in Washington D.C. the National Gallery of Art’s directory of artists features none from the Southern Hemisphere; they can be found in specialized collections in separate museums within a mile radius. In many American cities, artistic contributions outside the United States and Europe have historically been located in Museums of Natural History, reifying yet another disturbing dichotomy of nature/culture to be subliminally absorbed by the general visiting public. Retrofitting museums to become comprehensively critical and accountable to these curatorial legacies (and actually making lasting changes in their galleries) will continue to be the contemporary challenge to address for many cultural institutions.

Figure 4. In August 2020, the Museum of Man, one of the largest ethnographic collections in the United States, was renamed the Museum of Us. The two year renaming process reflects broader ‘decolonization of institutions’ initiatives that are impacting the arts and culture sector and greater calls for accountability to ethical curatorship and to the publics they serve.

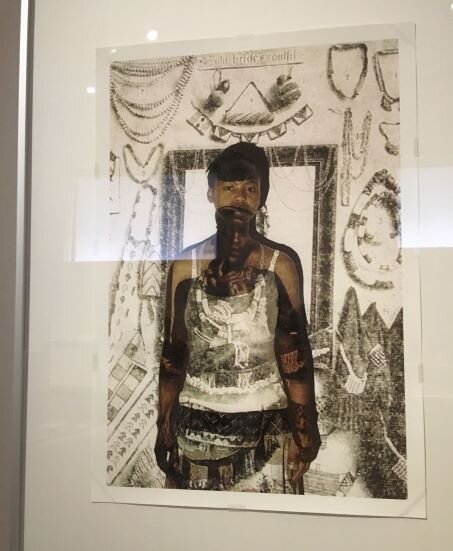

Additionally, inserting contemporary ethnological consciousness into art collections has the potential to deepen engagement with African artists’ commentary on curation and African aesthetic traditions and idioms. Another example from the Beyond Compare exhibit, the wall display “Photography and the “Other” that accompanies the work Imvunulo (Traditional Dress), showcases this possibility clearly (see Figure 5). The self-portrait overlaid with photographs magnifies the realities of how ethnographic [4] documentation has historically been produced: “Photographers often coerced their subjects into having their picture taken. Many of the images themselves were fantasies, reflecting the stereotypes and prejudices of the photographers.” (Bode Museum, Photography and the “Other”, 2017, Beyond Compare: Art from Africa in the Bode Museum: Germany). This exhibit item signals how developing complex and fluid vocabularies of the creator’s language of inspiration, including those derived from ethnographic encounters, are insights that art museum curators are positioned to provide and can constructively inform methodologies of comparison so fundamental for ethnographic collections.

Figure 5. Nomusa Makhubu, Imvunulo (Traditional Dress), 2013, Digital Print, Berlin, Bode Museum. This artist’s self-portrait is overlaid with a photo of an ethnographic display of Zulu wedding attire. Arranged under the catalogue’s theme “The ‘Others”, the clash of contexts interrogates how displays devoid of agency operated as the primary lens of perspective.

The gaze to Africa from the museum is currently undergoing rapid changes as these institutions audit the destructive colonial and imperialist histories and worldviews that have shaped their collections. Reflecting on my experience as a visitor to Beyond Compare in Berlin, several impressions remained about how new aesthetic arrangements can produce an ethically-charged framework for contemporary exhibit work. A valuable curatorial insight was that the story of the exhibit items did not stop and end with the glass case. The lineage of how these items came to be possessed and cared for, and for whom, enabled the presentations to avoid repeating ahistorical analysis of African art and expressive culture. Moreover, the concepts and pedagogical intent of the side-by-side arrangements permitted an engagement with the politics of the present-day, from correcting past errors of racism and ethnocentrism to policy decisions such as repatriation or removal of damaging items and presentations. Dissecting past practices and the potentially productive qualities of ethnological inquiry can offer needed cultural context for why European specimens sit on the pedestals they do, particularly for a public that is increasingly non-European, and particularly for cultural institutions, who in their refusal to repatriate collections of colonial provenance, justify their value as centralizing cultural opportunities for a global audience.

Acknowledgments

I thank Ruth Wenske for her incisive comments on an earlier draft of the essay.

References

Barnard, Alan. 2000. History and theory in Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapuis, Julien, Jonathan Fine, and Paola Ivanov. 2017. Beyond Compare: Art from Africa in the Bode Museum. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz.

Photography and the “Other”, Beyond Compare: Art from Africa in the Bode Museum, Bode Museum, Berlin, Germany.

Rowley, Neville. “The ‘Basilica’ in the Bode-Museum: A Central (and Contradictory) Space.” Kunsttexte.De (March 2015): https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/18452/8340/rowley.pdf

Statue of the Goddess Irhevbu or of Princess Edeleyo, Beyond Compare: Art from Africa in the Bode Museum, Bode Museum, Berlin, Germany.

Vermeulen, Han F. “History of Anthropology and a Name Change at the German Ethnological Society Meeting in Berlin: Conference Report,” History of Anthropology Newsletter 42 (2018): https://histanthro.org/news/observations/history-of-anthropology-and-a-name-change-at-the-german-ethnological-society-meeting-in-berlin-conference-report/.

Endnotes

[1] Ethnology is a particularly loaded term in German-speaking academia, as it relates to colonialism, National Socialism, and now the political right. The renaming of the German Ethnological Society to the German Association for Social and Cultural Anthropology serves as one current example of the contested status of this discipline (see Vermeulen 2018).

[2] The “object pairings” of the exhibit, in addition to its placement in a dedicated gallery, are interspersed within the permanent collection (see Figure 2).

[3] The current and former names of the collections -- Ethnologisches Museum (previously the Königliches Museum für Völkerkunde) and the Bode Museum (previously the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum) -- is one illustration of the tensions over ethnology/ethnological classification. While I am an anthropologist trained primarily in the British and American disciplinary traditions (and do not speak German), I do find it productive to leave in the terms “ethnology/ethnological” because it more comprehensively represents how cultural theories of the late 19th and 20th century were absorbed in both the humanities and social sciences and continue to remain imprinted in curatorial practices of European and North American cultural institutions.

[4] I use “ethnographic” here to mirror the specific language in the exhibit and catalogue, whereas most of this essay has used “ethnological” to be consistent to the German and European academic context and its specific application in museums. To elaborate on the slippage between ethnography/ethnology as disciplinary terms is outside the scope of this discussion.