Walking Alongside Others: An Interview with Lagi-Maama Academy and Consulting

We interviewed the members of Lagi-Maama Academy and Consulting consisting of Toluma‘anave Barbara Makuati-Afitu (Barbara), Kolokesa Uafā Māhina-Tuai (Kolokesa) and Hikule‘o Fe‘aomoeako Melaia Māhina (Hikule‘o) to find out more about their work in art, education and advocacy for Moana Oceania groups including diaspora in Aotearoa (New Zealand). We can consider their approach a form of weaving that operates cross-culturally for harmony through inclusion and partnership.

Citation: Mohan, Urmila, Emily Levick and Lagi-Maama. “Walking Alongside Others: An Interview with Lagi-Maama Academy and Consulting” The Jugaad Project, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2024, www.thejugaadproject.pub/interview-lagi-maama [date of access]

1. Could you tell us about how Lagi Maama started out? What was the impetus for the group, and what have been the highlights for you in your work to date, for instance, in the project documenting the arts of the 17+ island nations?

Toluma‘anave Barbara Makuati-Afitu (Barbara)

We have been told by our elders that Lagi-Maama was ‘divinely designed’, which we laughed at, but in hindsight, we think there were definitely forces in play as Lagi-Maama was never ‘our dream’ or even ‘a plan’, but as one of our dear Elders said, it was ‘our calling’.

Kolokesa and I ‘connected’ over a conversation around how to remunerate our Moana Oceania Holders of Knowledge appropriately – we cried over the same inequality and lack of knowledge and understanding of our Holders of Knowledge / our Onto-Epistemologists who are our cultural PhD holders, our archivists who hold in their time-space these knowledges, skills and practices that have been carried for generations.

But Lagi-Maama was birthed with a project called Alive with our Cambodian community, Rei Foundation, and an incredible Cambodian photographer named Kim Hak. This was an opportunity to unapologetically but strongly stand in our fullness and our ways of knowing, seeing and doing as Lagi-Maama and we are so grateful to our Cambodian community for allowing us to be part of their sharing.

We recall the words of one of our Cambodian leads, Dr. Man Hau Liev, on Lagi-Maama’s approach:

“I am so proud to see your work that reflects your professional team efforts and management with tact of this project. This success is due to your cultural respect and participation. You have chosen a difficult path to achieve cross-cultural harmony through inclusion and partnership”.

Highlights

Barbara

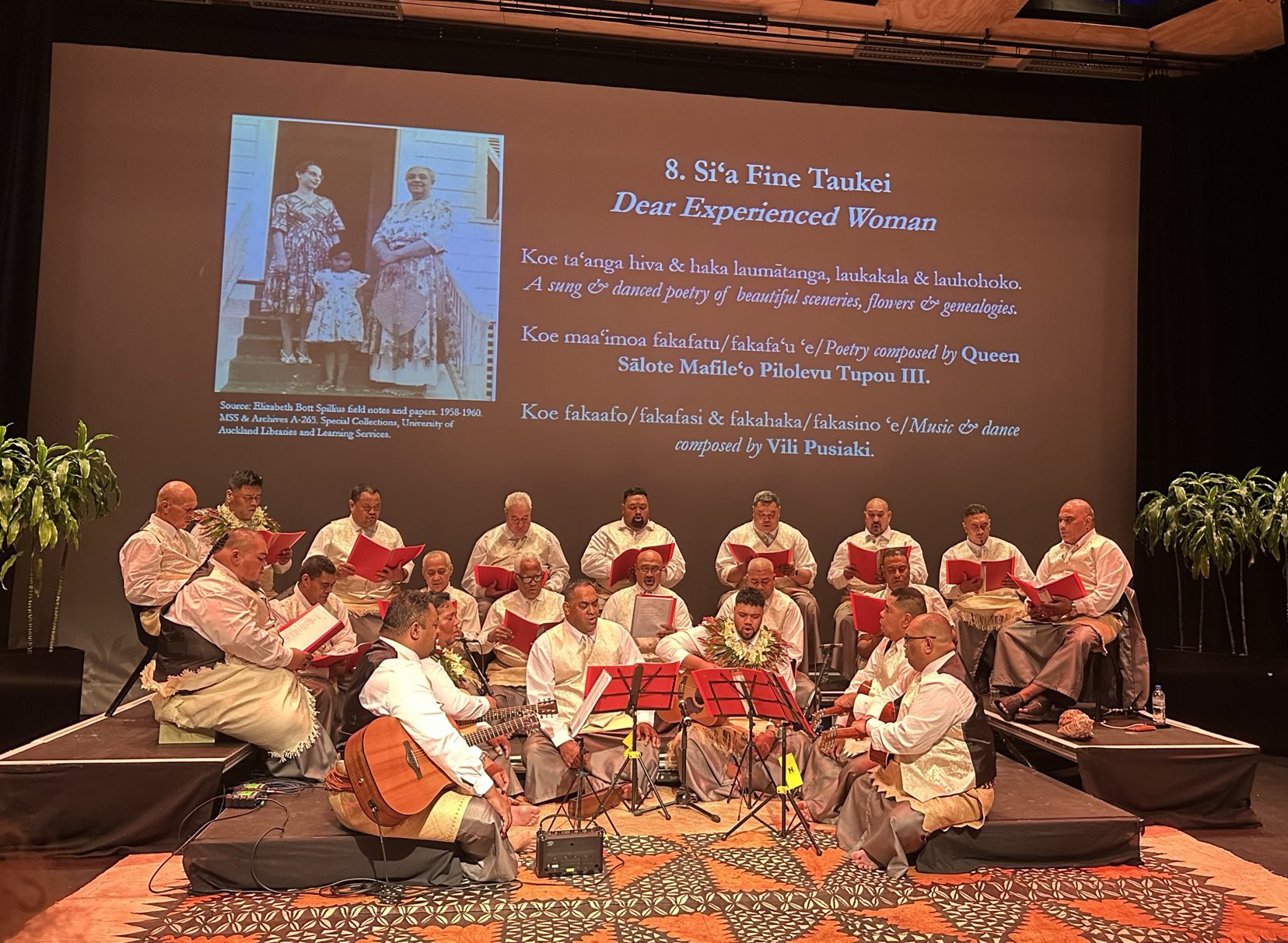

As for our highlights, that’s a hard one, but I think our ‘everyday’ highlight is being invited by our communities to walk alongside them through different projects and journeys. Our ‘walking alongside’ varies from group to group depending on what the level of need is – from providing advice to project management, securing funding, co-developing, co-curating, stakeholder management, mediating, and copy editing, to being in the kitchen catering and washing dishes. So the levels are supporting, facilitating, collaborating, and co-designing. We support our communities and projects throughout the whole process (and to be honest, with many of our communities there is no ‘full stop’ and is still continuing). An example of this is our journey with Feohi‘anga Ālonga ‘Ia Kalaisi, Unity-in Diversity in Christ Collective who we were introduced to in 2020 by one of our elders. His vision was to bring our ancient Tongan kava singing and fellowship into a theatre setting. Lagi-Maama sourced funding to support two concerts as well as two concert publications. Since then they have performed at conferences, at the World Choir Games, and Tongan cultural events with Lagi-Maama continuing to seek opportunities for the group to share their skills. All our projects to date have not been chosen by Lagi-Maama but brought to us by either communities, institutions, agencies or individuals.

Hikule‘o Fe’amoeako Melaia Māhina

I agree with Barbara - being invited by our communities to walk alongside them in their projects is a highlight in itself - and to add on to that, being gifted with their knowledge and vision for a project and being entrusted to do our best to bring it to fruition. Two really big highlights for me personally have been the Fenoga Tāoga Niue I Aotearoa - Niue Heritage Journey In Aotearoa exhibitions and publication, and the Tibuta Kinaakiia Ainen Kiribati - Tibuta Identifies Kiribati Women exhibition and publication. Walking alongside our communities as we went from an idea, through the journey of gathering and collecting and preparing, to delivering incredible exhibitions AND accompanying publications. So, so proud! I can't put into words the feeling of seeing all the Mamas and Papas coming through the galleries, and the pride and emotion sighting their names as makers on the labels next to their creations, or having school or community visits to the galleries and watching their faces light up when they recognise familiar names and faces or treasures on display that they have in their own homes. Witnessing the ripple and after-effects of all our projects is how we measure the projects impact and success.

2. What is the process involved in developing new projects, and how do you engage communities in your work? How do you define ‘community’, ‘tradition’, and ‘heritage’?

Barbara

To date, we have completed 60+ projects in collaboration with our communities, including exhibitions and publications to strategies, research, reviews, mentoring and curating – so our work spans across all areas where our ‘knowledge’ and Indigenous ways of knowing, seeing, doing and being, need to be acknowledged and privileged.

Our approach is centred around what our communities want to do –this requires some real ‘talanoa’ and mediation to see what is doable within that time-space. The concept and practice of talanoa as Samoan and Tongan is talking / conversing but to go deeper; it’s talking critically yet harmoniously towards a collective outcome.

We are led by them and our role is to mediate and bridge the gap between our Indigenous knowledges, skills and practices and formal institutions.

An example of one of our process-driven / community-driven / kaupapa drive projects is our Unity in Diversity and Diversity in Unity (UDDU) project. UDDU was an opportunity to look critically yet harmoniously, at the internationally renowned Moana Oceania drawings, by John Webber, expedition artist on Captain James Cook's third and final voyage in 1776 - 1780. This project focussed specifically on the Moana Oceania Webber plates that were published as part of the official publication of Cook’s third voyage and representing the five island nations of Aotearoa, Cook Islands, Tonga, Tahiti and Hawai‘i.

UDDU sought to fill a knowledge gap around some of John Webber’s works by providing the missing multiple Indigenous narratives. This required embracing different ways of knowing, seeing and doing to bring together, for the first time, a body of Indigenous knowledge and narratives specific to the Webber plates that were part of the official publication of Cook’s third and final voyage. These Webber images have been, and continue to be, widely used and referenced within and across cultural and academic spaces, so it was timely to provide a more balanced narrative by including what is missing – which is the knowledges from those being ‘sketched’, but key for us was to finally correct inaccurate information.

The knowledge gifted through UDDU for the Aotearoa image has now been added to the British Museum’s collections online records for this work – so the knowledge dictates the why, the process, the how, the when, and delivery.

We don’t ‘define or label’ knowledge, nor categorise it as ‘community’, ‘traditional’ or ‘heritage’ - knowledge is knowledge and as mediators we build platforms to privilege these knowledges from the multiple views representing our diverse communities. The issue with labels is that it ‘boxes’ our ways of knowing, seeing and doing which leads to perpetuating a cycle of inaccuracies, misrepresentations and misunderstandings.

3. What do you think is the essence and value of the textiles and fibre weavings made by the communities you have worked with so far?

Lagi-Maama

While we have had the privilege of walking alongside many of our makers and masters, we will share on two projects that feature textiles and weaving.

The first project was walking alongside two of our I-Kiribati ‘Mamas’ - Kaetaeta Watson and Louisa Humphry MNZM - around the significance of their tibuta, as Kiribati’s national tops worn by women and girls. Led by our Mamas, we created an exhibition and publication both called Tibuta – Kinaakiia Ainen Kiribati: Tibuta – Identifies Kiribati Women authored by I-Kiribati for I-Kiribati.

In the publication, Kaetaeta explains that:

“Tibuta has become very noticeably a Kiribati icon for I-Kiribati women. Louisa and I wanted to know more and started this research and journey on how tibuta came about. We encouraged some of our Kiribati people to come together so we can share our tibuta stories and make these first resources of an exhibition and publication about tibuta. So this project is really a platform for beginning a journey of sharing our knowledge together. We know there are elders and others that will also know about tibuta and they can continue adding to our collective efforts of recording our stories for generations to come.”

At the core of this project was the need to create tangible mediums, like an exhibition and publication that is led by for I-Kiribati women, and girls and the wider community to share the histories as told to them by their mothers and grandmothers on their ‘tibuta’. One contributor shared their thoughts on how the tibuta and how they believe- which , were was inspired by the Old Mother Hubbard dresses which were brought by the missionaries wives to cover up their beautiful Kiribati women. We collected stories spanning four generations, from four Kiribati communities across Aotearoa and even insights from the homeland including the Kiribati First Lady, Madame Teiraeng Maamau.

Louisa shared in in her story in the publication the following:

“We know te tibuta has taken on a new life and we know that the current First Lady Madame Teiraeng Maama has made it her mission to embed te tibuta as our Kiribati national attire. She has been a great advocate. It has also become part of school children’s wear and even government departments use it as office uniforms. All around the world wherever there are I-Kiribati and their families, you will come across te tibuta. It will always identify one as either I-Kiribati, friend of an I-Kiribati, has been to Kiribati, or has been gifted those treasures of tibuta.”

Furthermore, the essence and value of tibuta for Kiribati diaspora communities in Aotearoa New Zealand is best encapsulated in Louisa’s concluding words that:

“Tibuta will always be one form of attire that clearly identifies who we are and where we are from. When we wear our tibuta, it is always with pride to show our strong connection to our culture, language and customs from our beloved homeland of Kiribati.”

The second project that we wanted to share on, is our journey with Falepipi he Mafola Niuean Handcraft Group Incorporated who officially set up on the 1st April 1993 and have been going strong for over 31 years. They gather every Thursday at the Ōtāhuhu Town Hall Community Centre, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, between 10:00am – 2:00pm. In their 31 years’ journey, they have had 56 of their members pass away.

Molima Molly Pihigia QSM, as a founder together with her late husband Fataiki Tutolutama Pihigia, has been managing this group since its inception. Molly reached out to Lagi-Maama at their 25th anniversary, in 2018, wanting to ‘do something’ to acknowledge 30 years of their group. Led by Molly, we created an exhibition and publication titled Fenoga Tāoga Niue I Aotearoa, Niue Heritage Journey In Aotearoa.

Last year, on the 1st April 2023 – exactly 30 years to the day, we launched their exhibition with 350 of their works / their fine arts (predominantly weaving), DVDs and CDs, which were all displayed and played at Māngere Arts Centre Ngā Tohu o Uenuku, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, until 20 May 2023. The exhibition then travelled to Pātaka Art + Museum in Porirua, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, where it was on display from November 2023 until February 2024.

Falepipi he Mafola Group also published a 500-page book with stories and stunning images of their incredible works made by their hands. It was first launched in January 2024 in Niue, followed by a launch at the Ōtāhuhu Town Hall and then at Pātaka Art and Museum to close off their exhibition, both in February 2024.

As shared by one the reviewers of this publication, Philip Clark ONZM:

“The operation of the Falepipi he Malofa Niuean Handcraft Group bears the hallmarks of an elite institution of higher education. It has an unswerving focus on the transmission, and application, of traditional knowledge; includes contemporary subjects such as the Treaty of Waitangi; espouses a specific pedagogy; publishes in multiple formats; actively collects data and information; partners with other organisations; and over a considerable period has accumulated capital (in this case cultural rather than financial). Elite, because like elite academies it is actively concerned with the overall wellbeing (social and spiritual) of its membership. Its legal description might be ‘community group’, but step back and consider its operation, this organisation possesses the characteristics of an elite institution of higher learning.”

There are less than two thousand Niueans in Niue, and over 30 thousand here in Aotearoa – of which over 70% live in the Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland region. Falepipi he Mafola Group is one of many, many Niuean groups that are playing a vital role in preserving and maintaining their Niuean culture and heritage here in Tāmaki Makaurau and wider Aotearoa.

4. How do you include your specific type of Moana Oceania dress (Tongan or Samoan) in your clothing and appearance and at which occasions?

Barbara and Kolokesa

Barbara

As a Samoan I wear my Samoan-ness through my actions, my words and how I work. When going to certain functions, I will wear a ‘puletasi’ (two-piece made of skirt and top), otherwise I will wear what has been gifted to us by our amazing Mamas (makers) from our wider Moana Oceania communities, i.e. I will often wear earrings made by our Niuean community and use the fan made by our Kiribati Mama’s made from harakeke (flax).

Hikule‘o

As a Tongan, I wear a ta'ovala (waist mat) or a kiekie (ornamental girdle) for important or formal functions. Both serve as formal wear for Tongans and are a distinctive marker of Tongan identity. They are worn to church, special occasions, and even as part of the civil servants’ uniform, a tradition initiated by Queen Sālote Tupou III that is still observed today. The kiekie and ta'ovala that I wear are either made by my mother and aunts or are family heirlooms which have been passed down our family.

On a deeper level, Tongan society is grounded in the Four Golden Pillars or Faa‘i Kavei Koula. These are based on Tongan values of 'Ofa—Love, Tauhi Vā—Nurturing relationships; Loto tō—Humility; Faka'apa'apa—Respect. So, while I wear a ta'ovala or a kiekie, they are also a reminder to uphold these Golden Pillars in my actions and through the work that we do.

5. How have the ideas of Professor ‘Ōkusitino Māhina influenced this project and its approach to Moana Oceania?

Barbara

Professor Hūfanga-He-Ako-Moe-Lotu Dr ‘Ōkusitino Māhina has been a guiding light for Lagi-Maama from the very beginning - of gifting us our name to sharing the Tā-Vā Time-Space Philosophy of Reality, which is still guiding us in how we work and perform our duties.

This is best expressed in the following words from our website:

“We embrace our sense of time and space where in the present we symbolically walk forward into the past and backwards into the future, where the already-taken-place past (Pulotu / Fiji) and the yet-to-take-place future (Lagi / Sāmoa) are constantly mediated in the ever-changing, conflicting present (Maama / Tonga)."

So, this means that in the present, Lagi-Maama literally and in reality place the past in front of us as guidance, to inform the unknown future by the refined knowledge of our peoples and experiences of the known past. All of this is constantly negotiated and mediated in the work that we do in the knowing present.”

We acknowledge also our families and the villages we are blessed to have grown and continue to grow. We often share that our families – like Hūfanga-He-Ako-Moe-Lotu - are our biggest supporters but also our loudest critics.

6. How important is spiritual and ancestral power to Moana Oceania arts, today?

Lagi-Maama

VERY IMPORTANT!

As an Aotearoa-based educational and cultural organisation, our Lagi-Maama work has predominantly involved our Moana Oceania communities, of which we always privilege and foreground that there are 17+ island nations that have diaspora communities living here in Aotearoa.

Our ‘Arts’ of Moana Oceania research project currently addresses this – where we set out with the premise that if we are to genuinely understand and advocate for how the arts are valued and contribute to the wellbeing of all 17+ island nations with diaspora communities in Aotearoa, we need to first know ‘what is art?’ and then ‘what does art do’? from each of their 17+ worldviews.

Initiated in 2019, we have just completed our 18th island nation this year, of Aotearoa, with number 19, Samoa, in progress. The importance of spiritual and ancestral power feature strongly in the perspectives of all 18 island nations. We encourage interested readers to take the time and space to access these insights (in video and /or written formats) on our website.

This project is still going until we cover every island nation that has diaspora communities living in Aotearoa.

7. (We also included some questions specifically for Kolokesa Uafā Māhina-Tuai in light of her earlier work in curating textiles and fibre works.)

In the context of your earlier curatorial work, and the publications you shared with us on crochet, how are the makers or their families involved in curating and displaying the works in galleries?

When I place my curatorial journey in front of me, by walking forward into the past and backward into the future, I can truly say that it has been revolving and circular in nature.

What has been constant yet consistent is foregrounding and elevating the knowledges and practices of our different Moana Oceania communities. This has always been at the heart and centre of how I navigated my curatorial practice in the past through to the present with our Lagi-Maama approach of co-curating with our communities.

In reflecting back on this journey, I can say that there was a marked difference in the approach that I took in the earlier curatorial work that I was involved in where the exhibitions were informed by communities. The emphasis of my curatorial practice was more an activism role where the focus was either:

- addressing gaps in mainstream Aotearoa New Zealand history by giving “presence” to the histories and stories of our wider Moana Oceania peoples in Tangata o le Moana: The story of Pacific people in New Zealand (2007) at Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa;

- providing an Indigenous lens on ‘what art is?’ from Tongan views through Nimamamea‘a: the fine arts of Tongan embroidery and crochet (2011) at Objectspace;

- challenging the status quo (at that time and space) on the problematic distinctions and labelling of artists and their practices as ‘heritage’ and/or ‘traditional’ verses contemporary in Home AKL: Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland (2012) at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki; and

- enabling the first exhibition in a mainstream gallery on the making knowledges and practices of Tuvalu kolose or crochet with Kolose: The Art of Tuvalu Crochet (2014) at Māngere Arts Centre Ngā Tohu o Uenuku;

However, on the other hand, our Lagi-Maama curatorial approach is completely led by our communities where our process involves their input in co-curating and displaying of their works in the galleries. This is how we co-developed and co-produced the following two of our recent exhibitions and publications:

- Fenoga Tāoga Niue I Aotearoa, Niue Heritage Journey In Aotearoa (2023) with our Niue community; and

- Tibuta – Kinaakiia Ainen Kiribati: Tibuta – Identifies Kiribati Women (2023) with our Kiribati community.

Could you tell us more about your concern around language use and decolonising the terminology in exhibition interpretation practices? Why is it important to de-Westernise the language used to describe textiles, exhibited to the public?

My stance on the problematic nature of imposed terminologies has revolved and refined synonymously with my curatorial practice over the years. These concerns were based on real inequities that I was constantly yet consistently experiencing, first-hand, while working with, and advocating for, Moana Oceania communities and makers in all of the earlier exhibitions (mentioned in the previous question) that I was involved in prior to the ‘birth’ of Lagi-Maama. A comprehensive discussion of these concerns and issues can be read in the following paper published online in December 2017 called ‘The mis-education of Moana arts’. This paper was, however, written and first presented four years earlier at the 11th Pacific Arts Association (PAA) International Symposium in Vancouver, Canada, August 2013.

Five years later, in August 2018, Toluma‘anave Barbara and I officially set up Lagi-Maama Academy and Consultancy. As an Academy, we are involved in knowledge production by privileging our Indigenous ways of knowing, feeling and seeing, and as a Consultancy we implement by way of knowledge application through privileging our Indigenous ways of doing! So, we were set up with a foundation equipped for decolonising minds, hearts and hands.

At the end of 2019, early 2020, Lagi-Maama embarked on our ‘Arts’ of Moana Oceania (and Lagi-Maama Tok Stori Tuesdays) project that has enabled us to foreground new and known ways of doing art. The multiple knowledges and practices gifted were expressed and articulated in the diverse languages and terminologies of each respective island nation.

The language and terminologies that we use are crucial tools for decolonising. And when it comes to the material culture of a particular island nation, such as textiles and weaving, we would utilise and privilege their own language and terminologies for the exhibition labels and interpretation. This is how we empower the knowledge and views of our Indigenous communities and was the approach we took with our Niuean and Kiribati exhibitions already mentioned.

How has your dedication to the use of appropriate terminology impacted public perception of these textile and fibre works? Have you begun to see change in the ways people discuss or write about Moana Oceania?

In the work that we do as Lagi-Maama, we think and feel that to truly shift from a position dominated by the imposition of Western knowledge to a time and space of liberation through the application of Indigenous knowledges, requires removing terminologies with their baggage of imposed colonial knowledge, to utilising alternatives drawn from our own diverse and multiple languages and knowledge systems.

When Nimamamea‘a: the fine arts of Tongan embroidery and crochet exhibition opened in November 2011, it was accompanied by a bilingual Tongan and English publication that introduced into the “mainstream” GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums) sector an insight into knowledge on Tongan views of Tongan arts. For Objectspace, it was the first major project focused on making from the wider Moana Oceania. Philip Clarke, then director, wrote in the catalogue:

“Visitors can recognise the works in Nimamea’a as objects of beauty and skilled-making but it is through the curators’ fine writing that we can begin to appreciate how these works are different from other embroidery and crochet work produced in New Zealand today. These works have a completely different, and high, status within the arts of Tonga compared with the status of embroidery and crochet within the contemporary arts of New Zealand.”

This exhibition and publication were tangible examples and proof that were drawn on to highlight the problematic nature of Western-imposed terminologies that were applied to the textile and fibre works by master makers from Fiji, Kiribati, Tuvalu and Niue in the 2012 Home AKL:Artists of Pacific Heritage in Auckland exhibition. It was also the inspiration for the textile works featured in the 2014 Kolose: The Art of Tuvalu Crochet exhibition, which included a small bilingual Tuvaluan and English catalogue. This was the first Tuvalu exhibition in a mainstream art gallery and its success saw it travel to three other venues across Aotearoa.

2016 marked another shift with the term “Moana Oceania”, coined by Hūfanga-He-Ako-Moe-Lotu during the research and development journey for the book Crafting Aotearoa: A Cultural History of Making in New Zealand and the wider Moana Oceania that was eventually published in 2019, of which I was one of the authors together with Karl Chitham and Dr Damian Skinner.

This shift came out of the research process where we had brought together thinkers and doers to talanoa and gauged their thoughts and feelings of using the term Moana instead of Pacific in the book. At this gathering, Hūfanga-He-Ako-Moe-Lotu challenged us to be courageous and broker new ground by removing imposed terminologies such as ‘Pacific’ and its various transliterations of ‘Pasifika’, Pasefika in Samoan and Pasifiki in Tongan, in favour of embracing our own names like ‘Moana’ which means ‘Ocean’ in the languages of some island nations like Aotearoa, Cook Islands, Hawai‘i, Samoa and Tonga. His insistence is that when it was named Pacific in the 16th century, due to the calmness and ‘peaceful’ nature of the water, this does not reflect the depth and breadth of Indigenous knowledges of our Moana as an ocean of ‘both serenity and difficulty’, ‘connection and separation (or intersection), order and chaos, or life and death’.

Using the term Moana was, however, challenged by Julia Mage‘au Gray She expressed that ‘Moana’ does not mean anything to her because it is not part of her Mekeo, PNG vernacular. She shared that the term Oceania resonated more with her, especially in light of it being popularised and familiarised through the body of work of the late Professor Epeli Hau‘ofa.

In light of the issues raised by Julia, further talanoa continued with Hūfanga-He-Ako-Moe-Lotu, after this gathering, where he raised the point that, while Oceania is another imposed term that has been used interchangeably with Pacific, it has close affinity to Ocean, the meaning of Moana. And Oceania is known and understood by peoples from islands nations that don’t have Moana in their languages. His recommendation was for us to combine the two where we would still privilege the Indigenous name ‘Moana’ followed by ‘Oceania’, hence how the term “Moana Oceania” came into being. At this time-space, it served our purpose of finally doing away with a term that had been in existence for close to 500 years, and we were privileging a term, “Moana”, that exists in te reo Māori because Aotearoa was the context in which the Crafting Aotearoa book was produced.

When Lagi-Maama was birthed in 2018, we have embraced and embedded the term Moana Oceania into our ways of knowing and doing. However, we do want to reiterate that we only use “Moana Oceania" when we need to make general references to the region and her peoples. But when we work with specific island nations and communities, we would always privilege the name they use to refer to the region in their own respective languages and dialects.

Fast forward to 2024, where Lagi-Maama can definitely trace the trajectory of shifts in decolonising imposed terms and languages, which is a process that works synonymously with embedding and implementing our diverse Indigenous knowledge systems.