Re-Engaging Islamic Materials and their Heritage Values

Abstract

Coins have long been important materials for examining values and exchange networks in the past. Housed today in museum collections around the world, Islamic coins are no exception. But Islamic coins are more than simply material traces of the past, they also hold important contemporary meanings that have been overlooked and undervalued by academics. In this article, I share how I have begun to explore the possibilities for, and ethical commitment to, community involvement in the meanings and values that are constructed around museum-based materials. I discuss some results from my cultural heritage survey of people culturally connected to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. This survey contains individual-reported information about how individuals affiliated with the MENA region understand their relationship to museums, Islamic materials, and the construction of heritage. These stakeholder voices reveal the understated importance of museum-housed assemblages for cultural heritage and community values, including those that span across national borders, languages, and religious beliefs. This work envisions transformative approaches to collections and museum practice in which communities are recognized for their values regarding materials from the Islamic World’s vibrant past, rather than remaining the “recipients” of museum narratives and academic research.

Citation: Knutson, Sara Ann. “Re-Engaging Islamic Materials and their Heritage Values” The Jugaad Project, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2023, www.thejugaadproject.pub/islamic-coins [date of access]

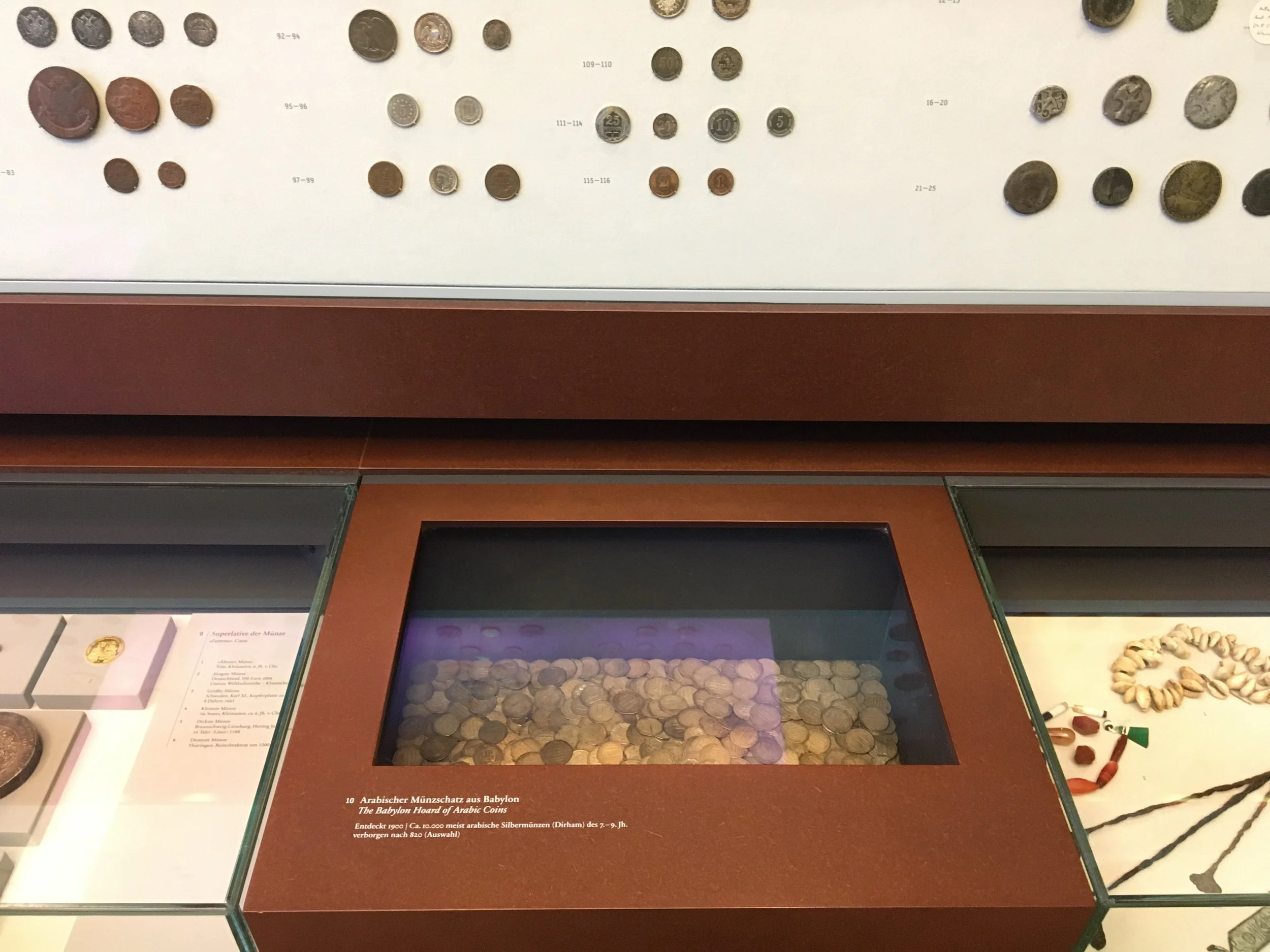

Housed beneath a glass case in a sage-coloured room rests an inconspicuous assemblage of coins. The case, covered on all sides but the top, restricts visibility of the assemblage (see Figure 1). The printed German tag reads, “Arabischer Münzschatz aus Babylon; Entdeckt 1900/ ca. 10.000 meist arabische Silbermünzen (Dirham) des 7.-9. Jh./ verborgen nach 820 (Auswahl)” (The Babylon Hoard of Arabic Coins, discovered 1900, ca. 10,000 mostly Arabic silver coins (dirham) from the 7th- 9th centuries [CE], concealed after 820 [CE] (selection)). [1] The “Babylon Hoard” is displayed at the Münzkabinett (Numismatic Collection) of the Bode-Museum in Berlin, Germany. With over 500,000 materials in its collection, the Münzkabinett houses one of the largest coin collections worldwide and, on a museum plaque, claims to be one of the “Big Five” (see Figure 2) although this latter assertion is less clear.

Figure 1: The “Babylon Hoard of Arabic Coins” display at the Bode-Museum, Berlin, Germany; Photo by Sara Ann Knutson, October 2021

Figure 2: “The Collections of the Numismatic Collection” plaques (in German and English) at the Bode-Museum, Berlin, Germany; Photos by Sara Ann Knutson, October 2021

Figure 3: Close-up of the “Babylon Hoard of Arabic Coins” display at the Bode-Museum, Berlin, Germany; Photo by Sara Ann Knutson, October 2021

As I balanced on my tiptoes to stare into the carefully covered glass case, I found the display of this coin assemblage curious for a few reasons. Firstly, the visual presentation of the coins—the case that requires the viewer to peer down into a partially illuminated but otherwise dark space to reveal anonymous, Arabic-inscribed silver—has all the orientalist trappings that I regularly teach students to critically examine. To be clear, the display of Islamic coins as “exotic” treasure is not unique to the Bode-Museum; this tendency pervades exhibits of Islamic materials throughout many museums and archives in Europe and North America and does little to address harmful biases towards Muslims, past and present—a point I will return to.

Secondly, the naming of the coin deposit as the “Babylon Hoard” requires critical examination. The coin assemblage was uncovered in 1900 by Robert Koldewey, a German archaeologist known for his excavations of Babylon, Iraq. Koldewey conducted archaeological work, for instance, on the Ishtar Gate (Koldewey 1913; Rogers 1915), which was subsequently looted and brought to Germany, where the ancient structure remains housed on the same “Museum Island” (Museumsinsel) in Berlin as the “Babylon Hoard.”[2] In light of its 20th century excavation history, the “Babylon Hoard” appears to be named after its findspot, Babylon, a city whose history extends far into the ancient past. The provided museum inscription, however, does not hint at this context nor justify the naming of an assemblage whose coins certainly do not date to ancient Babylonia (beginning in the 3rd millennium BCE). With this lack of context, the “Babylon Hoard” name seems instead to evoke, to my mind, images of an elusive, ancient Mesopotamian past, so often called the “cradle of civilization.” But the coins in this assemblage are not traces of ancient Mesopotamia—the majority are Islamic (‘Abbāsid era) coins, alongside a smaller portion of Sasanian coins, all of which were deposited as an assemblage sometime after (tpq) 204 AH/ 819-20 CE (Simon 1977; Heidemann 1998).

Figure 4: The “Babylon Hoard of Arabic Coins” (close-up) at the Bode-Museum, Berlin, Germany; Photo by Sara Ann Knutson, October 2021

Thirdly, the museum text reinforces my suggestions that the “Babylon Hoard” has been intentionally framed as an exotically ancient assemblage. The German text printed on the case (Figure 2) explains that the deposit was “verborgen nach 820” (concealed after 820, my translation and italics). This information identifies the terminus post quem deposition date, but the text interestingly uses the verb verborgen, which best translates to English as “hidden” or “concealed.” Verborgen, however, carries a connotation in German of passively being hidden. Compared to an alternative German word, versteckt, which connotes a more active sense of someone deliberately concealing materials in a deposit, verborgen may imply a more ancient, mystical quality—akin to “lost to the sands of time.” The curation of the “Babylon Hoard” is not neutral—curation never is—and reveals a certain fetishization of this predominantly Islamic coin assemblage.

The “Babylon Hoard” importantly reminds us of the issues at stake in the public display and curation of Islamic coins in Euro-western museums—and the stories we tell about such materials. Many museum visitors do not readily have access to the wide-ranging research and information available on Islamic coins, including those that are uncovered archaeologically. For instance, Islamic coins have contributed to numismatic research that help illuminate economic and social developments in the Islamic Caliphates, to anthropological questions of money and value, and to historical questions about networks of exchange and cross-cultural interactions in the Afro-Eurasian past.[3] But the meanings of museum-based coins are not confined to the values that museum practitioners curate to the public nor to the values that academic researchers ascribe to coinage as material traces of the past. The values of coins are not strictly about the past, but also about the present and future.

In a traditional academic publication, what normally follows now is an “I argue that” statement, but the following argument does not come from my positionality alone; while I acknowledge that my position here as the writer affords me certain power, I also wish to decentre my authorial voice—to the extent possible—and recognize that the following argument emerged from the voices of many stakeholders who culturally self-identify with the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region:

Islamic coins are material traces of the past and yet they are also more. These materials hold important contemporary meanings and values that have been overlooked in traditional academic research and museum settings.

This acknowledgment emerged from a digital survey that I developed and conducted in 2021 as I was writing my doctoral dissertation (Knutson 2022).[4] Available in both English and Arabic, the international survey sought anonymous reported information from individuals (aged 18 and older) who culturally self-identify with the MENA region in some capacity, including individuals who claim Middle Eastern- and North African descent, individuals who culturally identify and have family currently living in the MENA region, and individuals who culturally identify and grew up and/ or currently live in the MENA region. I also surveyed individuals who reported working in/ on/ for the MENA region in the cultural heritage sector or in a related field, like Anthropology or Archaeology.

I developed survey questions that were intended to gather information on how respondents understand their relationship to museums, Islamic materials, intangible cultural practices, and their engagement with cultural heritage.[5] Although I limit my discussion in this article to the survey results regarding the respondents’ cultural values of Islamic coinage, the survey itself also included general questions about their level of engagement with museums and which major museums, if any, in the Middle East and North Africa, Europe, and Central Asia they have visited.

The survey ran over six months in 2021 and when it closed, the survey contained approximately 130 responses. I chose the online survey method to engage stakeholders firstly out of global health considerations (this research took place during the COVID-19 pandemic) and secondly, in attempt to reach a wider range and number of people with different perspectives and positionalities around the MENA region and the world, beyond what I can capture with limited structured interviews with individuals in a limited number of locales. I also intended the survey to reach a wider scope of perspectives beyond individuals connected to my personal and professional networks, which, as with any individual, will inevitably contain biases and limitations. The survey was circulated online through identified listservs and newsletters, such as from relevant professional organizations and cultural institutions. However, the survey was primarily circulated (and reached its largest audiences) through social media posts, particularly in relevant Facebook groups oriented around cultural identity in the MENA region and abroad or around local urban communities in the MENA region. Finally, I should make clear that the results of this survey are not generalizable—I am not suggesting that these responses are in any way representative of the vast number of people who culturally identify with the MENA region, nor any other stakeholders connected to this region.

In terms of the survey response demographics, over half of reporting individuals in this survey self-identified as growing up and/or currently living in the MENA region (see Figure 5). A quarter of respondents identified their connection to the MENA region as individuals of Middle Eastern- and North African descent. Finally, slightly less than a quarter of respondents reported their connection to the MENA region as individuals who work in the cultural heritage sector or in a related field. Slightly over half (53%) of the survey respondents identified their religious identity as Muslim while the other half of respondents reported a non-Muslim religious identity or chose not to disclose this information (see Figure 6). Finally, the survey reached and appealed to individuals from a wide range of educational backgrounds, ranging from secondary school education up to a doctoral degree (see Figure 7). That said, taken as a whole, over half of respondents (55%) held advanced graduate degrees (masters or professional degree or a doctoral degree). It is therefore worth pointing out that there are biases to be expected in this survey data, as in all data, in regard to the demographics represented in this survey.

Figure 5: Reported Demographics of the (2021) Survey Respondents; Image by Sara Ann Knutson

Figure 6: Reported Religious Identity of the (2021) Survey Respondents; Image by Sara Ann Knutson

Figure 7: Reported Highest Educational Level of the (2021) Survey Respondents; Image by Sara Ann Knutson

The survey contained a variety of questions that ask respondents about their values and ascribed meanings to issues of museums, heritage, the past, and the present. Given that I wrote and developed these survey questions, this survey contains its own forms of curation and biases, shaped by my own positionality and research goals, and this observation too must be kept in mind. The respondents who participated in this survey also posed many important issues and valuable contributions beyond what can be discussed within the scope of a single article; these are part of ongoing conversations that will be shared in future venues. For our purposes here, I will discuss a survey question to which the responses have forever shaped the way I approach the research design of my work on Islamic coins and museum-based materials.

In the survey, I asked respondents: do you see ‘Abbāsid (Islamic) coins that are housed in European museum collection as part of your cultural heritage? Admittedly, this question may have been off-putting to some respondents who identified as individuals of white European descent, but this question was intentionally aimed to see the range of values and perspectives across stakeholders of various backgrounds. For the purposes of this article, I will focus on the responses of individuals who culturally identify with the MENA region, for whom the overwhelming response to this survey question was “yes.” To help understand the role of intersectional identities, I sorted the responses to this question by respondents who claimed Middle Eastern- and North African descent and/or who culturally identify and have family currently living in the MENA region and those who reported culturally identifying and growing up and/or currently living in the MENA region.

Among respondents who claimed Middle Eastern- and North African descent and/ or who have family living in the MENA region, 79% responded yes, they do understand Islamic coins housed in European museums as part of their heritage (see Figure 8). One respondent described that they identified with Islamic coins as a Muslim and that these materials therefore help them to understand Islam and its wider historical articulations in culture, architecture, and politics. Some respondents wrote that the coins connected them to their ancestors (“نعم، لان اسلافي عاشوا في الدولة العباسية” / “yes, because my ancestors lived in the ‘Abbāsid state”). Another respondent explained that “‘Abbāsid coins…belong to the political, socio-economic, and cultural environment in which they were created. I belong to this environment, thus I believe that these coins are part of my cultural heritage.” Some respondents selected “no” and explained that ‘Abbāsid coins are less meaningful to their cultural heritage than other materials: “They only represent one particular historical government.” Another individual selected no and explained that they felt no connection to Islamic coins because they had never seen one; this statement raises important questions about stakeholders’ accessibility to materials like Islamic coins, particularly those housed in Euro-western museums.

Among respondents who identified growing up and/ or currently living in the MENA region, 70% respondent affirmed that they see Islamic coins housed in European collections as part of their heritage (see Figure 9)—a similar statistic to the previously discussed group of respondents. A number of people described feeling connected to Islamic coins through their Arab ethnic identity. Some respondents associated these materials with a Muslim identity and that they “identify with [Islamic coins] regardless of where they are located.” One respondent explained that the coins bear witness to the historical relations between their country and the Arab countries, therefore associating Islamic coins to a heritage based on transnational connections (“هي تشهد على العلاقات التاريخية بين وطني والبلاد العربية” / “It bears witness to the historical relations between my country and the Arab countries”). Some respondents in this group selected “no,” explaining that the ‘Abbāsid association with these Islamic coins instead evoked a history of invasion and exploitation. One respondent wrote “yes” and expressed frustration that Islamic materials are displayed in countries where Islamophobia remains a problem. This understanding of the hypocrisy of Euro-western museums and countries who benefit from the display of Islamic materials but meanwhile do nothing to address harmful biases towards Muslims is a powerful point that resonates widely among stakeholders connected to the MENA region but is too often missing from many conversations in academic research and in the museum sector.

Figure 8: Survey response among respondents who claimed Middle Eastern- and North African descent/ who culturally identify and have family living in the MENA region; Image by Sara Ann Knutson

Figure 9: Survey response among respondents who identify growing up and/or living in the MENA region; Image by Sara Ann Knutson

The responses from this survey question alone, and the wider issues that the respondents’ comments raised, reveal multifaceted perspectives. The respondents also identified some complex ways in which their relationships to museum-housed Islamic coins inform the construction of cultural heritage or in some cases, where these materials may not hold meaning for some individuals, sometimes for reasons that are fundamentally the consequence of the enduring legacies of colonialism. These important stakeholder values reveal, not least, the wide range of identities and meanings that such museum-based materials evoke. These coins undoubtedly do not hold the same meanings to everyone, and they certainly do not need to. Some stakeholders understand these materials more narrowly, as traces of the ‘Abbāsid Caliphate as a past political entity, while other stakeholders understand these materials as encompassing a range of religious and ethnic identities and perspectives that are still relevant to the MENA region and the wider Muslim community.

The provided feedback at the end of the survey was overwhelmingly positive, encouraging, and constructive. Respondents took on average 20 to 30 minutes to complete the survey and share their thoughts and experiences and I am deeply, enduringly grateful to each individual who contributed their time, perspectives, and values to this research. The survey respondents, as well as stakeholders beyond the survey, are helping me to consider important, timely issues and the implications of the research I engage in. To each of these individuals: thank you, for taking time to teach me and allowing me to listen.

In discussing some stakeholder feedback that I received from the survey, I have shared a part of how I have begun the enduring task of incorporating stakeholder values into my research. I also intend this piece as a small contribution to existing conversations, rather than as a model of what museum-oriented research must necessarily look like in every local context. The point of the survey was to identify community values regarding museums, intangible cultural practices, and museum-based materials. The survey revealed, not least, that many stakeholders claim Islamic coins as valuable to their heritage—a point that very few researchers and Euro-western museums have thought to raise. I should note that the survey did not ask respondents about their impressions about any specific museum or museum display, although this would be a compelling area for future research that would align with a large body of scholarship on museum visitor experiences and interactions.[6]

Outside of research on Islamic coinage, academics have also become more aware in recent years that materials housed in Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums (sometimes called GLAM institutions) indeed offer important opportunities for material evidence, such as coinage, to contribute to current societal debates. Practitioners within the discipline of Archaeology, for example, are engaging important questions of how “GLAM”-based evidence can be used to decolonize and democratize Archaeology and expand the impact of research to benefit local communities and in consultation with community values.

These kinds of conversations are beginning to take seriously that instead of only asking what academic research and museums can offer local communities, we need to modify the premise of this question. We must identify specific ways to create space for local community members to be actively involved in research and museum narratives from the beginning, not simply the end. This means creating space where community values inform research design and important stakeholders are properly recognized for their own unique sets of intellectual expertise, rather than remaining simply the recipients of research outcomes and narratives. I am not alone in these conversations on how to practice ethical community involvement, collaboration, and partnership and these practices take on different forms in different local contexts.

For my part, I hope to contribute a greater understanding of the ways in which museum-based materials, like those Islamic coins on display in the Bode-Museum, so often carry contemporary values—they are not simply traces of the past. Museums must bear this ethical consideration in mind. The “Babylon Hoard” offers a reminder that the decisions that inform the representation of museum-based materials are never neutral and they carry implicit assumptions—assumptions that can have profound implications for living communities. The work towards more ethical museum displays begins with museum practitioners and researchers reflecting on their positionalities, questioning their assumptions, asking the question of who the important stakeholders are, and involving those stakeholders and their values from the start of the process. This work can make the difference between a museum display that exoticizes “ancient” assemblages—and therefore, inappropriately exoticizes the spaces and communities from whom these assemblages emerged—and a display that honours the community values that heritage materials point to. This is not to suggest that contemporary values are homogenous or without factions or competing meanings. The survey results revealed that heritage contains complex identities and a plurality of meanings that museum institutions and stakeholders alike must hold. In my own learning journey, this work has also meant committing to questioning why certain academic or museum conventions exist and who these conventions serve, destabilizing the presumed division between academia and the “public,” identifying the important stakeholders, and listening. Listening far more than I will ever speak—or write.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the two anonymous peer reviewers for their comments and insights that greatly improved this article.

References

Alshehaby, Fatimah. 2020. "Cultural heritage protection in Islamic tradition." International Journal of Cultural Property 27(3): 291-322.

Alzoud, Hassan A. 2017. The Age of Harun Al-Rashid: Through Historical Sources and Coinage. Amman: Jordan Ahli Bank Numismatic Museum. [in Arabic]

Ashtor, Eliyahu. 1976. A Social and Economic History of the Near East in the Middle Ages. London: Collins.

Bacharach, Jere L. 2006. Islamic History Through Coins: An Analysis and Catalogue of Tenth-Century Ikhshidid Coinage. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Black, Graham. 2012. Transforming Museums in the Twenty-first Century. London: Routledge.

Crooke, Elizabeth. 2007. Museums and Community: Ideas, Issues and Challenges. London: Routledge.

Doering, Zahava D. 1999. “Strangers, guests, or clients? Visitor experiences in museums.” Curator: The Museum Journal 42(2): 74-87.

Falk, John H. 2016. Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience. London: Routledge.

Heidemann, Stefan. 1998. “The Merger of Two Currency Zones in Early Islam. The Byzantine and Sasanian Impact on the Circulation in Former Byzantine Syria and Northern Mesopotamia.” Iran 36 (1998): 95-112.

Knutson, Sara Ann. 2022. Pieces of Change: Uncovering the Material Networks that Transformed Ancient Eurasian Interactions. Doctoral Dissertation, University of California-Berkeley. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Koldewey, Robert. 1913. Das wieder erstehende Babylon. Die bisherigen Ergebnisse der deutschen Ausgrabungen. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichssche Buchhandlung.

Kovalev, Roman K. and Alexis C. Kaelin. 2007. “Circulation of Arab Silver in Medieval Afro-Eurasia: Preliminary Observations.” History Compass 5(2): 560–580.

McDowall, Felicity A. 2023. “Lost in temporal translation: a visual and visitor-based evaluation of prehistory displays.” Antiquity 97(393): 707-25.

Mulder, Stephennie. 2021. "Expanding the ‘Islamic’ in Islamic heritage." Archaeological Dialogues 28(2): 125- 127.

Noonan, T.S. 1984. “Why Dirhams First Reached Russia: The role of Arab-Khazar relations in the development of the earliest Islamic trade with Eastern Europe.” Archivum Eurosiae Medii Aevi 4: 151-282.

Peutz, Nathalie. 2017. "Heritage in (the) Ruins." International Journal of Middle East Studies 49(4): 721-728.

Rico, Trinidad. 2017. “The Making of Islamic Heritages: An Overview of Disciplinary Interventions.” The Making of Islamic Heritage: Muslim Pasts and Heritage Presents: 1-11.

Rogers, Robert W. 1915. A History of Babylonia and Assyria. Vol 1. 6th ed. New York: The Abingdon Press.

Simon, Hermann. 1977. “Die sāsānidischen Münzen des Fundes von Babylon, ein Teil des bei Koldeweys Ausgrabung im Jahr 1900 gefundenen Münzschatzes.” In Textes et Mémoires. Vol. 5. Varia 1976. Acta Iranica 1977: 149-337.

Smith, Laurajane. 2021. Emotional Heritage: Visitor Engagement at Museums and Heritage Sites. Oxon: Routledge.

Van Alfen, Peter G. 2000. “The ‘Owls from the 1973 Iraq Hoard.” American Journal of Numismatics 12(2000): 9-58.

Wakefield, Sarina (ed). 2021. Museums of the Arabian Peninsula: Historical Developments and Contemporary Discourses. London: Routledge.

Further Resources

Al Quntar, Salam. 2017. "Repatriation and the Legacy of Colonialism in the Middle East." Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 5(1): 19-26.

Atalay, Sonya. 2012. Community-based archaeology: Research with, by, and for indigenous and local communities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Erskine-Loftus, Pamela. 2010. "A brief look at the history of museums in the region and wider Middle East." Art & Architecture 13(Winter/ Spring 2010): 18-20.

Hicks, Dan. 2022. “Letter to a Young Archaeologist, December 2022.” Accessed 22 February 2023.

Knutson, Sara Ann. In press. “Interactions of Change: Pursuing Agentive Materials and Intangible Movements along the Silk Road.” In Branka Fanicevic and Marie Nichole Pareja (Eds.), Imperial Horizons of the Silk Roads. Oxford: Archaeopress, 112-135.

Mickel, Allison. 2021. Why those who shovel are silent: a history of local archaeological knowledge and labor. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Rosenzweig, Melissa S. “Confronting the present: archaeology in 2019.” American Anthropologist 122.2 (2020): 284- 305.

Wylie, Alison. 2019. "Crossing a threshold: Collaborative archaeology in global dialogue." Archaeologies 15: 570-587.

Endnotes

1. All quoted German and Arabic translations in this text are my own, unless otherwise noted.

2. Note that this assemblage name is not to be confused with an unrelated coin deposit that was uncovered in 1973, which scholars also sometimes refer to as the “Babylon Hoard,” the “Mesopotamia Hoard,” or the “Iraq Hoard.” For information on the 1973 hoard, see Van Alfen (2000).

3. See, for instance: Alzoud (2017) and bibliography within, p. 201, for citations of published catalogues of Islamic coins; Ashtor (1976); Bacharach (2006); Kovalev and Kaelin (2007); Noonan (1984).

4. This survey received approval from the University of California, Berkeley Committee for Protection and Human Subjects (CPHS) and appropriate guidelines were followed.

5. For scholarly discussions of heritage in Islamic contexts, see: Peutz (2017); Rico (2017); Alshehaby (2020); Mulder (2021).

6. See, for instance: Doering (1999); Crooke (2007); Black (2012); Falk (2016); Smith (2021); Wakefield (2021); McDowall (2023).