Transformations on the Margin: Jack Smith’s Vital and Difficult Art

Abstract

Jack Smith was a visionary American filmmaker, photographer and avant-garde performance artist who was born in 1932 and died of a HIV/Aids related illness in 1989. His immense courage, self-assurance and the strength of his uncompromising vision are truly remarkable. He employed discarded film stock in making his movies, enlisted amateur, often first-time performers and transformed them into underground superstars. And in making his idiosyncratic art, the entire process of assembling the filmic scenes, getting actors dressed and made up took on the compelling elements of a ritual, the journey enshrined in the process itself became thoroughly ritualized and ultimately transformative. Part of Smith’s power as an artist, which is frequently akin to the inexplicable appeal of cult leaders, is in being able to get his co-travelers to believe in the transformative dimensions of his singular art events. Devoid of crass materialism and virtually no form of mainstream support, the journey and experience were essentially edifying and often life changing. The fact that an artist can adopt lowly, discarded film materials, in other words trash, marginal people and seemingly marginal subjects, operate in marginal and disavowed contexts obviously provide the grounds for transmogrification, indeed the conditions through which an alchemist such as Smith might prove his mettle, and which he did with aplomb and almost incredible results.

Citation: Osha, Sanya “Transformations on the Margin: Jack Smith’s Vital and Difficult Art.” The Jugaad Project, 2 June 2021, thejugaadproject.pub/jack-smith [date of access]

“The world that he [Smith] lived in had great appeal, and it also had a terrifying lack of boundaries. Within his hermetic realm, it was utterly logical, and everything he did made perfect sense. Outside that magical kingdom, he was quite mad, and though his madness was essentially benign, it could wear you out.”[1]

As Jack Smith the visionary American filmmaker, photographer and avant-garde performance artist lay dying in 1989 at New York’s Beth Israel Hospital, he was still as irascible as ever. Performance artist, Penny Arcade, and poet and filmmaker, Ira Cohen, were two of the remaining figures from New York bohemia who still possessed the stomach to endure Smith’s impossibly ornery disposition. When Allen Ginsberg, the American poet and writer, visited him, Smith derisively called him “a walking career”[2], a derogatory term for an artist who sold out or for upholding the apparently despicable values of careerism. Irving Rosenthal, author of the countercultural novel, Sheeper, issued by Grove Press in 1967, was labeled “a control freak” by Smith when he attempted to visit him in hospital. Rosenthal, a major culture catalyst and facilitator, acted as a bridge between the avant-garde world and mainstream culture. He wanted to preserve Smith’s filmic work in a vault in faraway California but the latter wasn’t enthused with the idea. As this essay explores, the rejection of Rosenthal’s suggestion was in keeping with Smith’s character and fit into a way of living, and adherence to values that alienated him from the recognition that he, ironically, desired.

Lack and Invention

Jack Smith was born in 1932 and died of a HIV/Aids related illness in 1989. His immense courage, self-assurance and the strength of his uncompromising vision were truly remarkable. He employed discarded film stock in making his movies, enlisted amateur, often first-time performers, and transformed them into underground superstars. And in making his idiosyncratic art, the entire process of assembling the filmic scenes, getting actors dressed and all made up took on the compelling elements of a ritual, the journey enshrined in the process itself became thoroughly ritualized and ultimately transformative. Smith’s art was about seeking a rare transformative moment of experience that abolishes the unbearable profanity of the mundane. As a child, Smith, like some (e.g. Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Jean Jenet) other gifted artistic personalities, felt unloved and unwanted by his mother. He even blamed her for prompting his homosexuality. And so he retreated into the enclosed world of his fertile imagination. But unlike so many other emotionally aggrieved people, he resolved bring to life the contents of his imagination without even having the wherewithal to do so. Using the endowment of sheer belief, he transformed himself into a filmmaker without formal training. Employing the powers of vision and charisma, he was able to convince ‘nobodies’ that they could become film stars and finally, using low grade and discarded film stock, he created masterpieces of underground cinema. Each plateau of progress in his existence had been attained through feats of radical transformation from aggrieved boy to transcendental artist, abandoned film stock to underground filmic masterpiece, everyday nobodies transformed to underground superstars via rigorous processes of ritual and hard-earned transcendence. In this vital sense, nothing can become something.

Still from Flaming Creatures, 1962-63. Film by Jack Smith. 16 mm film, black and white, sound.

The entirety of US or in fact global counterculture was quite small and throughout his life, Smith was fortunate to meet such catalysts of transition, the first of whom was Jonas Mekas, filmmaker, culture critic, activist and archivist. Mekas established the Anthology of Film Archives and the Filmmaker’s Cooperative for the purpose of showcasing and preserving films produced by the counterculture. In 1963, Smith had directed the landmark, Flaming Creatures, which broke all rules of traditional cinematography. There is nudity aplenty, a graphic rape scene and elaborate ritualized performativity in addition to a strict non-reliance on storyboards and ‘normal’ narrative structure. The film, when released, could only be shown after midnight and not in normal daytime theaters. It fell upon Mekas to promote the film which was awarded a prize by his periodical, Film Culture. The journal also became the vehicle through which Smith developed his ideas on film in essays such as “The Perfect Filmic Appositeness of Maria Montez” and “Belated Appreciation of JVS (Josef von Sternberg).” Through such writings, his influential remarks on trash were disseminated; “Trash in the material of creations. It exists whether one approves or not.”[3][4]

Still from Flaming Creatures, 1962-63. Film by Jack Smith. 16 mm film, black and white, sound.

As soon as Flaming Creatures was initially exhibited in the United States, the censorship battles commenced. Prints of the movie were confiscated by police working on behalf of censorship boards. Mekas, on the other hand, served as a judge of an underground film festival in Knokke-le-Zoute, Belgium and fought to see the film was shown at the event but was prevented. In protest, Mekas resigned as a judge and exhibited the film in his hotel room before an audience comprising film luminaries Agnes Varda, Roman Polanski and Jean-Luc Goddard.

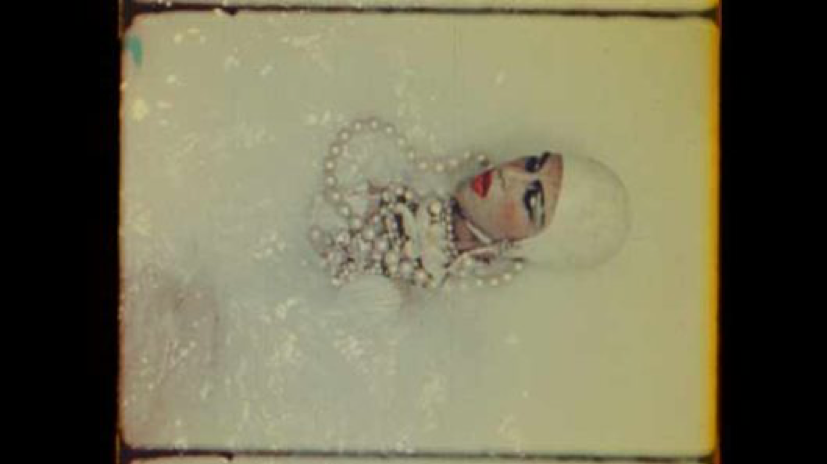

Still from Normal Love, film by Jack Smith, 1963-65, 16 mm film, color and sound.

Smith crossed paths with another major cultural figure, Andy Warhol. Warhol claimed Smith was the only movie artist he could ever imitate and had indeed learnt much of his filmic practice from the former especially whilst Smith was shooting Normal Love in the mid nineteen sixties. During the period, Warhol had absorbed the significance of improvisational skills in filmmaking and the Smithian credo that the performance invariably supersedes the character.

Still from No President, 1967-70. Film by Jack Smith. 16 mm film, black and white, sound.

After the difficult circumstances surrounding Flaming Creatures’ release, Smith’s practice was further radicalized and he chose never to formally complete another movie. His subsequent works, Normal Love and No President remain uncompleted as at each showing of both films, he was constantly re-editing them, adding new scenes and deleting some others, most probably in an attempt to elude the intrusive power of the censors and other authorities.

This approach conflicted with ideas in the underground movie scene in which a sacrosanct, in other words, complete and finished work is required. Perhaps due to the hostility and resistance faced by the practitioners of underground film, it was necessary to define and establish the rules and parameters of their practice to distinguish insiders from outsiders. Naturally, due to unsympathetic conditions they faced, they would have had to demarcate the borders of their genre and so their shared understanding of completeness, in this light, would be probable. On this score, he parted ways with his benefactor, Mekas who thought Smith was simply being crazy.[5] Through Smith’s approach, film and performativity, where language can function as a form of social action and have the effect of change, were hurled into a state of flux which made improvisation and experience the key elements of the film.

Part of Smith’s power as an artist (akin to the often inexplicable appeal of cult leaders) was in being able to get his co-travelers to believe in the transformative dimensions of his singular art events. Devoid of crass materialism and virtually no form of mainstream support, the journey and experience were essentially edifying and often life changing. The fact that he could adopt lowly, discarded film material, in other words trash, whether conceived as objects, marginal people or seemingly marginal subjects, meant that Smith operated in marginal and disavowed contexts. This provided the grounds for transmogrification, indeed the conditions through which an alchemist such as Smith might prove his mettle, and which he did with aplomb and almost incredible results.

Smith’s Flaming Creatures addresses the then taboo themes of androgyny, de-gendered and de-centered sexualities (an exposed phallus in unable to act as one and remains resolute in its flaccidity, or perhaps its value is no more than an ornament for an enchanted circle of odalisques), transvestitism and nudity and undercuts any suggested attempt at populism. In addition, there was something dark and mysterious about the manner in which Smith chose to interrogate those themes which was a far cry from the New Age philosophies of flower-bedecked children of sunny California that were prevalent at that time among his contemporaries. Within that small and off-beat ambience, Smith painstakingly fabricated a striking universe of make-belief out of inferior film stock, trash and social cast-offs all magnificently shrouded in garish lights. Smith’s work seems to advance the view that through a sleight of osmosis, smut and garbage could alchemically become art. Many insightful critics claim that Flaming Creatures is an extraordinary feat of the imagination, courage and innovation made on no-budget.

According to Mekas, “Jack Smith has just finished a great movie…[But] Flaming Creatures will not be shown theatrically because our social-moral etc. guides are sick…This movie will be called pornographic, degenerate, homosexual, trite, disgusting etc. It is all of that, and it is also much more than that. I tell you, the American movie audiences today are being deprived of the best of the new cinema, and it’s not doing any good to the souls of the people”.[6]

Incompleteness or Silence

When it became too financially prohibitive to continue to make films, Smith turned to performance art of which he has been called “the daddy” by Charles Ludlam[7], founder of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company. His practice of performance art went on to be exceedingly influential with its DIY origins, inexpensive yet sturdily imaginative make-shift sets and its shifting and protean creativity. In spite of its charmingly rudimentary or minimalist nature, and ceaseless interrogation of the links between art and life, its creative basis remained decidedly Smithian; somewhat odd, self-contained and free.

As a performance artist, Smith evolved a practice that abolished the distinction between art and life. Part ritual, part rehearsal, part formal performance, part stretches of ennui, Smith courageously deployed this fusion of elements that totally destroyed received opinions regarding traditional theater. He sought to attain the magical through a conscious transmogrification of the self, and by extension, the collective, which in this case, meant the audience. However, this transmogrification, akin to an intense spiritual experience, came at a steep price; it entailed the expulsion of “the scum of Baghdad” [8] as Smith labeled those deemed unworthy of the communal experience due to their impatience, lack of rigor and stamina. As for the price of admittance for the chosen, it came as a crucible of endurance, the patient awaiting of the moment when the transformative dimension unexpectedly appeared. Indeed, within the Smithian canon, the manifestation of art encompasses an almost epiphanic element.

This exclusivity would contradict Smith’s view of art as constituting a leitmotif of the social fabric thereby creating tensions between visions of an elitist art and a populist art. This conflict extended to Smith’s distrust of capitalism in relation to socialism since he often had problems making his rent. In his view, nothing was more predatory than the omnipresent figure of landlord in our predominantly capitalist world. In Mary Jordan’s fascinating documentary, Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis, Smith continuously rails against the commercialization of art, which in his view, has led to its devaluation. According to him, capitalism equals the “mutilation” of art when it ought to be advancing its dissemination and establishing its centrality in everyday life. In addition, “by internally re-imagining tenant-landlord and gay-straight struggles, Smith destroyed home-workplace, script-production and audience-audience dichotomies exemplifying how content, media, art and life overlap one another”.[9]

Smith sometimes contradicts himself but the ideological thrust of his approach is clear enough. His art is about embarking on an arduous experiential journey in which the ordeal of systematic elimination is a constant reality. With this being the case, the experience of gaining ultimate satisfaction from his art can only be at best limited. This characteristic of incompleteness remains definitive in his singular art.

The other definitive feature of his work is its inevitable confinement to the counterculture. His art, variously described as “baroque and broke”[10] represents a direct opposition to pop culture as exemplified by Andy Warhol. Where Warhol embraced and celebrated the capitalist ethic, espousing the features of mass production, instant advertising, glamour and celebrity, Smith went for trash, incompleteness and de-commodification. Whereas Warhol learnt from him and utilized his concepts, Smith could gain nothing in return. Eventually, Smith also shunned the likes of Mekas, Ginsberg and Rosenthal, veritable facilitators and supporters of the counterculture. Ginsberg was responsible for much the media furor that engulfed the Beats as a movement and also helped establish the ‘Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics’ at what is now Naropa University (then Institute) in Boulder, Colorado. Rosenthal co-founded the ‘Kaliflower Commune’ with George Harris, and from this transgressive scene another agent of transformation emerged in the form of the ‘Cockettes’, a gender-blending performance troupe that blithely mixed deliberate gaucheness, trash, cheap glitter and transsexual tropes.[11] Smith had access to this artistically incestuous scene but he wound up alienating most of its players.

Toward the ending of Jordan’s documentary, Smith bemoans what appears to be his lack of commercial success; “It’s my fault. I haven’t been organized properly…I was never organized nearly enough. I didn’t know those things.” He didn’t also know how to pander but knew extensively how to offend and alienate people. Basically, by his subject matter and approaches to art, he could only have encountered a degree of appreciation only within counterculture circles. That he never seemed to understand this truth is rather baffling. In a fit of pique and despair, he had instructed Penny Arcade to burn archives of his work in order to deny posterity the privilege of judging him. However, he openly pined for widespread acceptance even as he broke every rule and code leading to that ordinarily treacherous route. Indeed, it is remarkable how such an otherwise visionary artist could be so lacking in insight regarding such a crucial aspect of his own work.

Enrique Vila-Matas, the Spanish author, argues that the contemporary writer—and he may well have been speaking about artists generally- faces three main options regarding her work. First, she could elect to shackle herself to the rules of the market and thus become a “grey, competent writer.”[12] She could also choose to pursue an underground and totally unknown oeuvre; and finally, she could enter the publishing industry and break as many of its rules as possible until her subversive activities are eventually noticed and she is unceremoniously expelled. Obviously, Smith chose to pursue an underground and unknown oeuvre even if he wasn’t always enamored of the results.

Smith had great difficulty in breaking into the mainstream circles of commercial cinema. His mother could not send him to a formal film school even though he obviously had the talent due to financial reasons. And so he embarked on a journey of artistic self-discovery by trial and error, fervent experimentalism and adventurous transformation; transformation, first, of the self, the meaning and purpose of art, and finally, the materials that were utilized in creating art. When he was able to produce his major film opus, Flaming Creatures, he encountered both critical and commercial resistance and this affected him deeply. Without major funding, no established film stars and with discarded film stock, he had been able to create a marvel of the imagination and yet his work was not appreciated. Instead, he was vilified and his work was banned in several US states. After this shattering experience, he resolved never to formally complete another movie. In a way, completion and artistic finality came to signify vulnerability to censorship and artistic mutilation or misrepresentation. And paradoxically, incompleteness, came to imply an index of resistance to the power structures that defined and censored art. Smith’s life and work demonstrate that a condition of absolute lack is not necessarily to be equated with inadequacy, inactivity and ultimately, failure. Instead such a negative condition can actually lead to an unparalleled release of the powers of the imagination and creative energy. Furthermore, such an ostensibly deprived state can in fact be inspiring occasion to reconsider the meaning of art, the role of the artist and the arrangements of our systems of societal values and artistic valuation.

References

Enrique Vila-Matas, “Writers from the old days”, The White Review, July 15, 2015

Mary Jordan Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis, independent release film, 2006.

Irving Rosenthal Sheeper, New York, Grove Press, 1967.

Film Culture, a periodical Jonas Mekas established in 1954 to showcase and critique underground cinema.

Endnotes

[1] https://www.artforum.com/print/199708/gary-indiana-52089

[2] http://pennyarcade.tv/friends/the-last-days-and-moments-of-jack-smith/

[3] Jack Smith, “The Perfect Filmic Appositeness of Maria Montez”, Film Culture, Winter 1962/63.

[4] Ibid.

[5] This idea was truly revolutionary but the infrastructure through which it could be explored and developed was lacking. Not even an important culture facilitator such as Mekas was willing to provide a welcoming platform.

[6] Jonas Mekas, cited by Amy Taubin in “Jonas Mekas’s Movie Journal”, Artforum, April, 2017.

[7] Consult, Mary Jordan’s documentary, Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis, 2006.

[8] Consult, Mary Jordan’s documentary, Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis, 2006.

[9] Mark Block, “Jack Smith: Art Crust of Spiritual Oasis” The Brooklyn Rail, Jul-Aug, 2018.

[10] Consult, Mary Jordan’s documentary, Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis, 2006.

[11] Henceforth, Rosenthal’s work entailed a subversion of the capitalist ethos via a rigorous ethic of self-sufficiency, fastidious Indian mysticism and counterculture outsiderness. Indeed his notion of ‘dropping out’ incorporated an almost spiritual component that reached deeper than the more popular view promoted by the existential adventurists and flower children of the sixties.

[12] See Enrique Vila-Matas, “Writers from the old days”, The White Review, July 15, 2015.