The Classics in Soap: An Interview with Meekyoung Shin

Meekyoung Shin was born in Cheong-Ju, Korea in 1967. She trained in Korea before moving to London in 1995 to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, and she now works between London and Seoul. Sculpted primarily in soap, her work often uses Greco-Roman imagery to explore themes of translation, transience, and the movement of people and artefacts across cultural boundaries. Her recent solo exhibitions include ‘The Abyss of Time’ held at the Arko Art Center in Seoul in 2018, and the 2020 ‘Weather’ at Barakat Gallery in London.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Figure 1. Screencapture from the artist’s Instagram of her 2014 show at the National Centre for Craft and Design. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

JH. Meekyoung Shin, thank you for talking to me for this special issue of The Jugaad Project. There are so many ways that your work resonates with our theme of translocality, but in this interview we’re going to focus on your experiences as an artist working between Korea and the UK, and your interactions with classical Greek and Roman sculpture. Can I start by asking when you first came into contact with ancient Greek and Roman art?

MYS. Well, I went to Greece on my way to Britain in 1995. But I’d already encountered Greek sculpture in Korea when I was quite young. I went to Art High School, which is a specialised school for talented young people. That was the practical side of sculpture, but I did also look at some art history books at that time. It was Western art history rather than Eastern art history that we studied. We had to draw Greek or Roman busts, or model them in clay, and that’s how we learned art. We worked with classical portrait busts made out of plaster, and for me, the classical felt very contemporary, very ‘present’. However, when I came here to London, no one was really interested in it. It was seen as old, and dated.

JH. Did you also study sculptures from the Korean tradition, when you were in art school in Korea?

MYS. That’s the funny thing: in art school at that time you studied far more Western Classical art, rather than Korean (although it’s a little tricky to divide Western and Eastern very clearly). I don’t know why – I’m still wondering about that. But in Korea, the way of life was very Westernised already. And back then, I didn’t think “well, that’s Western, and we’re Eastern.” I didn’t think that the world was divided like that until I came to London. Then when I arrived here, I thought – “Oh I’m Asian, and the things I study are Western things.” That was the first time I realised that there was a divide. When I came to live here in London, I realised that I come from a very different background. The language, the culture – this was much different from what I imagined before.

JH. How did you imagine London, before you arrived here?

MYS. I didn’t have too many expectations or pre-formed ideas, apart from the usual things like red double-decker buses, or Buckingham Palace, which I’d seen on television. I didn’t know more than any ordinary tourist. But when I actually got to London, I started thinking “I’m a different creature. This is why my art should be different.” So then I started looking to my past. Then, after I arrived in London I went to the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum, and saw the things that I’d previously seen only in pictures, in the plates of art history books, or in the form of plaster copies.

JH. Had you visited museums when you were growing up and studying in Korea?

MYS. Yes, my mum is a painter, so I visited galleries and museums from a very young age. Nowadays there are countless museums in Korea, but thirty years ago there weren’t many contemporary art museums at all. The contemporary art that I saw at that time was mostly Korean painting, and it was often the work of my mum's colleagues. I visited foreign art shows when I could, but these were pretty rare.

Figure 2. Meekyoung Shin’s ‘Kouros series’ (2009), part of her ongoing ‘Translations’ project. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

JH. So when you left Korea and travelled to Greece and the UK, how did it feel to see the ‘original’ marble sculptures that you’d always previously seen as photographs in books, or as plaster copies?

MYS. Well, it was funny to see the Parthenon in Athens and then go to see the Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum. To me it looked a bit like taxidermy, because I knew that originally these sculptures had been standing in the open air, in the dust and noise. In the museum they seemed like dead animals – things that were not alive or moving any more.

The fact that the Parthenon sculptures had been moved to London – that made me think about issues of origin and authenticity, and what happens when we move things somewhere else. In a way, they become completely different objects. Context changes things. It’s the same with me. I started out in Korea, and then moved here to London, and all of a sudden, I was very different. Like a Parthenon sculpture or pillar moving to Britain and into the British Museum, all of a sudden, I had a very different context.

JH. And did you carry on working with classical sculpture when you first got to the Slade?

MYS. Actually no. At that time, I was trying to do something more abstract, and to forget about classical things.

Figure 3. Photographs of an early work from Meekyoung Shin’s first year at the Slade (1996). Materials: wax, concrete, human hair, heating element. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

JH. Can you tell us more about that early period of work? What was it like?

MYS. In those early works at the Slade, I often found myself imagining what happened to the body during the transition from life to death. And I was very interested in the concept of ‘residue’. When someone is alive, the body is very figurative and vertical. When they die, it becomes abstract, and horizontal. I made this piece [see above] using wax, which I thought looked just like human flesh. It incorporated my own hair, and the face was modelled on my boyfriend at the time. This was a performance piece, which used a heating element to melt the wax. It took 45 minutes to melt.

Figure 4. Photographs of an early work from Meekyoung Shin’s first year at the Slade (1996). Materials: wax, fabric, tinted water. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

Another early piece comprised a white vest, cast in wax from my own body. This was akin to a container, which I filled with red water, like blood. There were tiny, needle-sized holes in the vest, and I let it bleed over the course of a few days. This piece was about exploring feelings of emotional hurt through a physical ‘happening’. I’ve always liked the idea of the sculpture itself performing, or acting.

JH. What was the reaction of your Slade tutors to the work you were doing at this early point? Were they interested in your cultural background?

MYS. Yes, they were very interested and supportive. I think that I was the first student that the Slade had ever had from Korea. The environment there was completely different to what I’d been used to. Back home, I had already done two solo shows, and I basically been working on my own for three years. Nobody was really interested in what I was doing. I think that many people assumed that I would get married soon, and leave the art world. There weren’t many women colleagues there, either. But when I came to London, the tutors read my work, and it was super-interesting to interact with them. They didn’t know me well, but we still managed to communicate.

JH. Looking at these early works, you can definitely perceive some of the themes from your later work already appearing here – such as the passing of time, and bodily decay, which you explore so powerfully in your soap sculptures. In your later work, though, these themes of ‘time’ and ‘body’ are also intertwined with ideas of cultural exchange and ‘translation’ (to cite the title of one of your longest series of soap sculptures). When did these latter themes start taking shape?

MYS. I started focussing on these issues quite naturally, because as soon as I arrived at the Slade I started running into problems with my English. And it wasn’t just the language issue – there were just so many cultural differences. I’d grown up in a single-culture society, where everyone understood me, but suddenly I needed to explain even the simplest things. It was a completely new experience for me, because I had graduated from a very prestigious high school and university, and I had never needed to explain myself from scratch.

It was quite challenging, but in a positive way as well as a negative one, because suddenly nothing was ‘normal’, and it gave me the opportunity to start completely at the beginning again. When I was a young artist in Korea, I wanted to produce work that engaged with the theme of identity, but I didn’t really know how to, at that point. When I started my MA at the Slade School, I thought “Where can I start? How can I communicate to these people? They don’t know me at all, and I don’t know them either.” I tried to show, tried to…confess where I come from, and how I am different.

Figure 5. Screenshot from the artist’s Instagram showing her performance in 2003 at the British Museum. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

JH. So when did you start working with classical Greek and Roman models again?

MYS. Well, another thing that struck me at this time was the similarity between art and language. I started to think about how we learn classical art in Korea, and how it’s similar to learning a Western language. When we learn a language, we often just copy rather than re-articulate things. And it’s the same with sculpture, too. But when I came here, I realised that I could use the classical tradition to say something new. And so I started to become interested again in the classical stuff.

Visiting the London museums, the thing that I really noticed about the classical sculptures was that they looked a lot like soap. That itself could have been a foreigner’s perspective, because the marble in Korea is very different from European marble. It’s very rough, and very, very strong. And it’s not easily carved like Italian or classical sculpture here. I’d always wondered how they carved the drapery effect on classical sculptures, but when I saw the real material I realised “Ah, that’s how!” And then I had the idea of re-creating these sculptures in soap.

JH. Had you ever worked with soap as a sculptural material before that point?

MYS. In Korea, when you are at primary school, every twelve-year old student starts to make sculpture with soap, because soap is easy to carve. I think almost every child learns how to carve with soap. That’s my own very strong memory. It’s a very domesticated material.

Figure 6. Meekyoung Shin, Translation – L’Innocenza Perduta by Emilio Santarelli (1962) (1998, restored 2009). 80 x 60 x 227cm. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

JH. Once you’d rediscovered soap as a sculptural material at the Slade, what was the first work you made?

MYS. I’ve lost the very first sculpture I did, which was a Greek goddess figure. I’d made it from a piece of soap that I found at the Slade, which was the size of a pebble, and slightly pink. After some more small-size pieces, I then considered making a version of Rodin’s Kiss. I’d read an article about how its display in Lewes [in 1914] had been controversial, because it was considered too sexual as an image. And I thought that I could make the same piece out of soap.

But then I saw a nineteenth-century neoclassical sculpture in the corridor of the Slade: L’Innocenza Perduta by Emilio Santarelli. One day I saw a restorer cleaning this sculpture, very carefully, and at that moment I realised that the meaning of an artwork is something that is created over time. So I made a soap sculpture of L’Innocenza Perduta. It had a flesh-coloured body, evoking the nudity of Rodin’s figures too.

JH. The colour question is really important, isn’t it? Classical art historians and museum professionals are now making more effort to explain how classical sculpture was originally colourful, not like the pale, monochrome sculptures we have today. Can you talk a bit more about colour, in relation to your work?

Figure 7. L’Innocenza Perduta, work in progress. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

MYS. Colour is really important. With Innocenza Perduta, I made a flesh-coloured body, then the transparent dress on top. I was trying to make the sculpture really light, and more life-like – something which is alive, as well as a reference to older sculpture. I chose a pink colour, which resembles skin, in a general sense. It’s funny, in Korea they used to sell a colour of soap called ‘skin colour’, which probably isn’t politically correct. But when I was young, there were zero foreigners living in Korea.

This was all tied up with the other sensory qualities, like smell. Because both the colour and the fragrant smell of my sculptures confuse people’s ideas about what sculpture is meant to be. When you look at Greek art in the museum, you no longer have the original colour, or the smells, or even the sound of an environment like the Parthenon in Athens. All these things are vacuumed out in the museum. I really want to make my work appeal to more than just the sense of sight. Nowadays, lots of artworks are only seen in images, photographs online – and we think we know them. But when we see a real piece of sculpture, we realise that there was something missing in the photographs. So I always try to explain to people that if they don’t see my work in person, then they are missing out, and they don’t get a full understanding of it.

JH. Did you know at that time that ancient Greek and Roman sculptures were originally painted with different colours?

MYS. Yes, I learned that from my personal tutor at the Slade, Edward Allington, who had a great knowledge of Greek sculpture, and of almost everything else. Before that, I’d always believed that the sculpture was originally white. But that isn’t true. One of my hobbies at that time was trying to find traces of colour on the statues in the British Museum.

JH. As well as its colour and scent, another of soap’s qualities is how quickly it can erode. In the preface to your exhibition catalogue Translations, you write about the importance of ephemerality and decay intrinsic in the medium, saying “Soap has the ability to show the passage of time and the mundane. As a common, everyday material, it can exhibit a temporal flow in a compressed way because of its trait of easily wearing out” [1].

Figure 8. An early work by the artist. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

MYS. Yes, that’s another reason why I choose to work in soap. Ancient marble sculptures like those in the British Museum marbles are eroded by time, and they make us question the possibility of permanence. I try to make a connection with that idea with my soap sculptures. My work is about materiality, but it’s also about time – how we express time, and how we play with it. For example, in my Written in Soap project, I recreated a monumental equestrian statue of the Duke of Cumberland which had once stood on the same spot [in Cavendish Square, London]. Statues like this were commissioned by Roman emperors and others rulers, and they wanted them to be there forever. As an artist, I am subverting that by making the statue disappear. It’s almost the opposite of their original function.

It’s the same with the Toilet Project, which is a long, ongoing project of mine. It’s all about exploring how artefacts ‘come into being’ over time. In this case, I put soap sculptures in bathrooms, and people erode them by washing their hands, after which the sculptures are moved to a gallery, where they become artefacts. I don’t ‘make’ artefacts, but they come into being from people using them, over time and through history. With the soap sculptures in the Toilet Project, I cast them in a series to look all the same, but every single one comes back looking different. It’s a strange way of making uniqueness and authenticity.

Figure 9. Screenshot from the artist’s Instagram of the Toilet Project (2004-on going). Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

JH. There have been some quite strong reactions to the Toilet Project, particularly around the Buddha soap statues, is that right?

MYS. Yes, that’s right. Buddhist don’t like these images, but then Christians don’t either. Nobody likes them! Christians don’t want to see them – they cut the heads off and throw into the sink. Buddhists don’t like them either, because they think that images like this shouldn’t be in the toilet. For many people, it was the religious aspect of these images that was at stake, even though that wasn’t my intention. That has been very intriguing to me. I am simply working with iconic images, which in this case includes the Buddha statue, alongside the classical images.

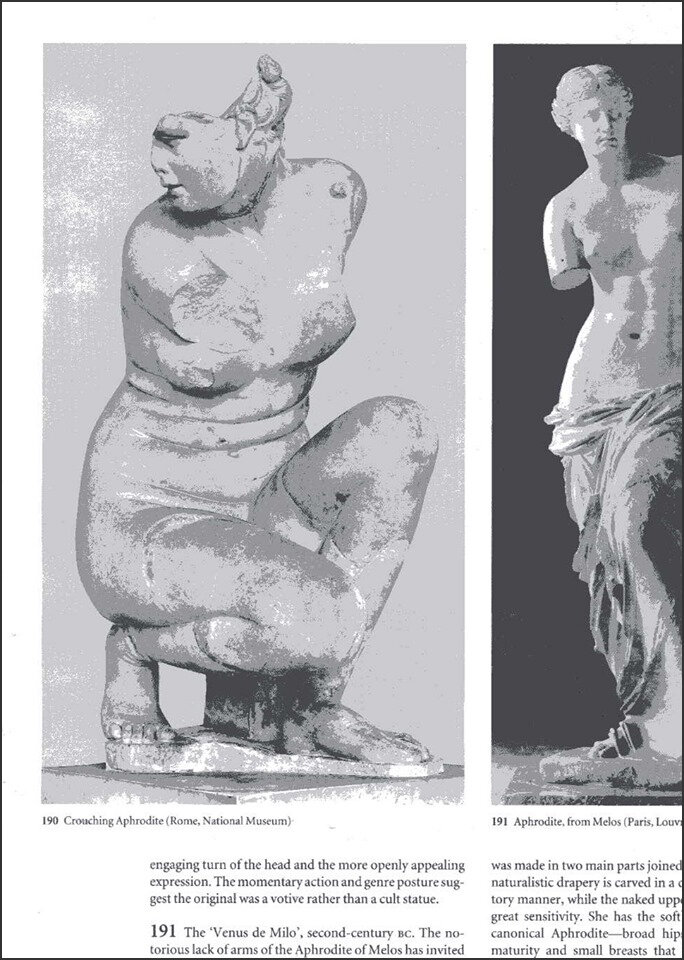

JH. Picking up on this point about the iconic…. It is so significant, isn’t it, that you’ve choose to work with the most familiar and iconic examples of classical Greek and Roman art – things like the Venus De Milo and Crouching Venus, which are instantly recognisable to so many people, and which somehow carry the burden of the whole classical tradition. How does this choice of iconic objects relate to your concerns with translation, and communication across boundaries?

Figure 10. Photograph of bookplate used by Meekyoung Shin during the creation of her ‘Crouching Venus’. Photograph courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

MYS. In my work, I choose images that are so iconic that they are almost banal, and then I play with them, to make something new and different. In the case of the Crouching Venus, I worked entirely from the photographic plates in one of my textbooks about classical art. Most people are introduced to classical art via books. They never see the ‘real’ object, but they still feel like they know the sculpture, even if they haven’t seen it in person. In this case, I looked at the book, then posed as the sculpture myself, and took plaster casts from my own body, then I used those casts as the model for my soap sculpture.

Figure 11. Making the ‘Crouching Venus’. Photographs courtesy of the artist. ©Meekyoung Shin.

And it is fascinating to see people’s reactions to these images. For instance, some Westerners find it strange and uncomfortable that ‘their’ old stuff is being made by somebody from the East. They seem to be thinking “How she can make that so well?”

Then, on the other hand, when I had a solo show in Korea, some of the curators asked me, “Don’t you have any work that’s more Eastern?” So I said to them “How can it be more Korean than this? It’s full of Korean aspects, of ‘Koreanness’”. But they just look at the surface, and since they don’t see any obvious Korean symbols or techniques, they miss the point. Some artists do simply borrow obvious cultural symbols or techniques to state their identity, but the results are often very shallow, if you see what I mean. For me, identity isn’t just embedded in how a work looks, but it’s about the whole approach or attitude towards a work. People need to understand why I’ve made a particular work, not just what it looks like.

JH. Meekyoung Shin, thank you very much.

Endnotes

[1] Meekyoung Shin (2009). ‘The concept of translation’, p. 7, in Translation. Exhibition Catalogue, Kukje Gallery.

Find out more

Instagram for Meekyoung Shin

Citation: Hughes, Jessica. “The Classics in Soap: An Interview With Meekyoung Shin.” The Jugaad Project, 22 Jul. 2020, thejugaadproject.pub/home/meekyoung-shin [date of access]