Not Writing as Not Seeing, Not Recording: Embodied Racism in Indonesia -- Reflections on Fieldwork since 1974

Citation: Rodgers, Susan. “Not Writing as Not Seeing, Not Recording: Embodied Racism in Indonesia -- Reflections on Fieldwork since 1974.” The Jugaad Project, 15 Jul. 2020, thejugaadproject.pub/home/not-writing-as-not-seeing [date of access]

In guest curating an exhibition called “Power and Gold” in 1983 and 1984 for the Asia Society Gallery in New York City, I travelled to Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines for four months of fieldwork interviews with local museum staffs and with owners, users, and crafters of the types of ritual ornaments that we displayed to international visitors in the show. From these conversations and from the archival record, it became clear to me that many of Indonesia’s 200-plus ethnic societies had interacted in sometimes politically compromising ways with the Netherlands East Indies colonial state. At times, local chieftains and traditional nobles had forged self-serving alliances with agents of the colonial state after having been granted favors, or money payments, or gold coins for their collaboration with empire. In Eastern Indonesian islands, the gold coins were sometimes converted into new, shiny versions of old decorative ornaments that had once been made of more modest materials such as shells, rattan, or feathers. For instance, in Nage society in the island of Flores, high nobles had once announced their high status to their local publics by wearing tall crowns (called lado) made of feathers. After contact with the colonial state (which expanded beyond Bali, eastward, in the 19th and early 20th centuries) Nage aristocrats started to wear magnificent gold frontals. These took the form of the older feather crowns yet now used that classic symbol of exalted social position: lustrous gold. The Nage gold frontal was an arresting image – a truly stunning piece of jewelry. Not surprisingly, the “Power and Gold” exhibition, its publications, its wall texts, and the first image that museum visitors saw as they entered the exhibition all employed a sharp color photograph of this Nage precious metal crown. As the guest curator of the exhibition, I was happy with these museum installation and printed materials decisions. After all, the gold crown caught visitors’ and readers’ attention right away and was, indeed, an aesthetically lovely object. The crown even graces the cover of the book I wrote for the exhibition (1985, Power and Gold: Jewelry from Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, Musee Barbier-Mueller and, in later editions, Prestel).

Lado wea or gold frontal, Nage area, Central Flores, Indonesia. 1983, Photograph by Musee Barbier-Mueller, from S. Rodgers, Power and Gold, 1985. Image credit: Susan Rodgers.

But, I never hesitated to go beyond aesthetics to write about and lecture about the ways that this crown (hardly just an ‘indigenous ornament’) embodied morally murky political interactions between Nage elites and Dutch colonial administrators and their colonial business partners. This sort of political analysis of material culture, grounded in colonial histories, has always been something I pride myself in doing, in all my work with Indonesian arts in museum exhibitions and in print.

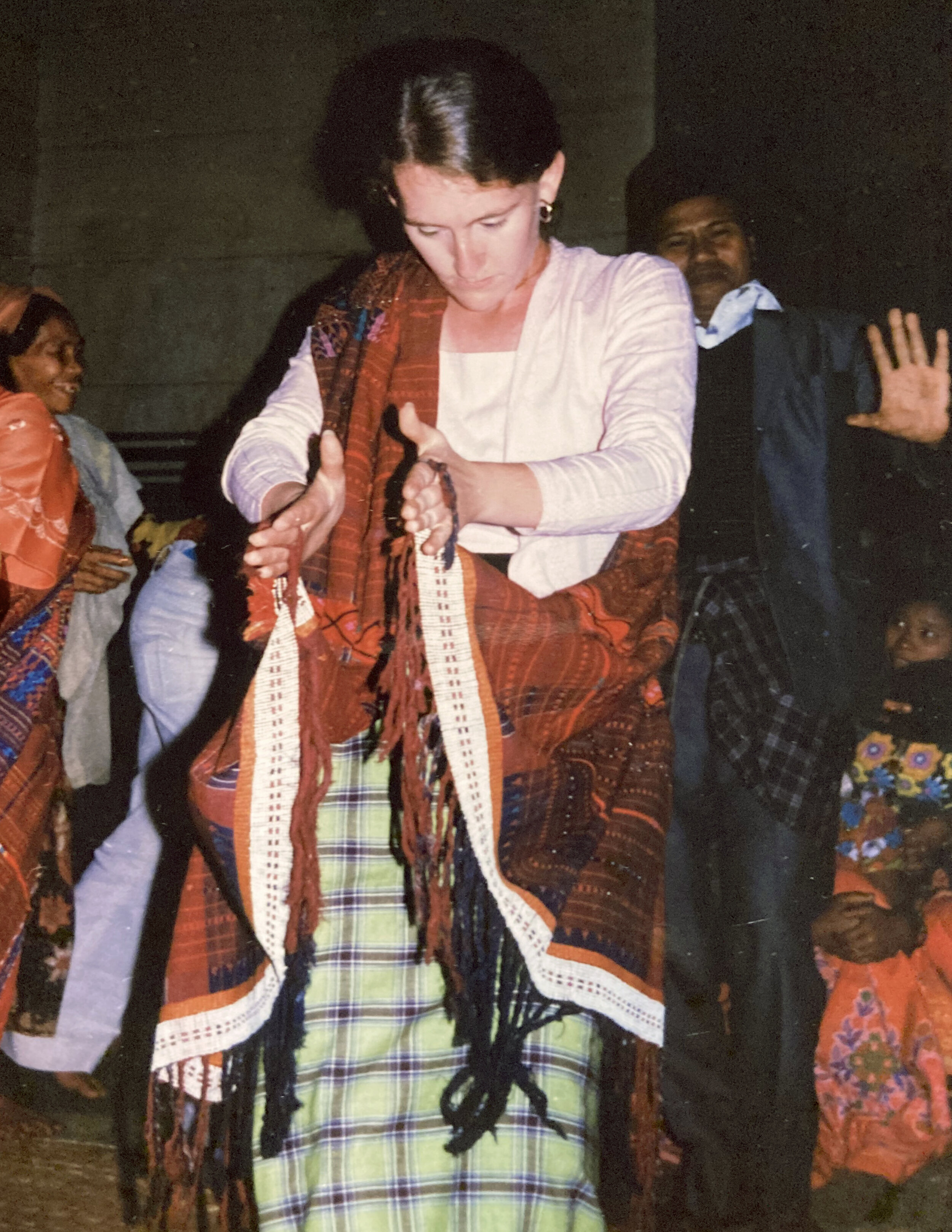

The author doing a tortor dance at a Sipirok-area horja ceremonial feast, 1976. Image credit: Susan Rodgers.

However, I regret to say, this forthright willingness to comment upon and deconstruct some of the political underpinnings of Indonesian “local” arts stands in marked contrast to my muteness over the years in never writing about body and race in contemporary Indonesia, specifically as those complex ideological and behavioral issues relate to the ethnic Chinese in the nation. This community is sometimes referred to as Chinese Indonesians or Indonesian Chinese. Some of these individuals and families have lived in Indonesian islands for over 200 years; some Dutch colonial business owners, with government support, favored the ethnic Chinese as intermediaries between the Europeans and the bumi putra, the sons-of-the-land, the members of ‘indigenous Indonesian ethnic societies.’ Other Indonesian Chinese immigrated to places like Sumatra much later, in the 1920s and 1930s, in search of jobs in manual labor, the transportation sector, and petty commerce (as fruit sellers or peddlers, for instance). In national times after the 1945-1949 Indonesian revolution, Indonesian Chinese thus have occupied a wide variety of positions along the Indonesian economic spectrum, as wealthy business people but also as struggling families in marginal trades. But, when I first arrived in North Sumatra in 1974 as a 25 year old doctoral student in anthropology, eager to begin my dissertation fieldwork about Angkola Batak[1] oral and print literatures in a little mountain town in Tapanuli, North Sumatra, I quickly discovered that the “halak Cino”, the Cino people (that is, the Indonesian Chinese, a few of whom were resident in the larger Tapanuli towns) were hotly resented and publicly reviled as (supposedly) greedy, sneaky, conniving, uniformly “very rich” people who only cared about themselves and plotted constantly to take economic and social advantage of the good people – that is, the bumi putra. These comments were racist slurs and I was being fed them by Angkola Batak friends, teachers, and landlords with whom I was becoming increasingly close as my two and a half years of initial fieldwork in Tapanuli unfolded.

I knew that these opinions about the so-called halak Cino were vicious and factually untrue. I well understood that the word “Cino” has a slur-like quality. The anti-Indonesian Chinese drumbeat of criticism by my Batak friends also had a bodily element to it. Batak older people would sometimes praise me as being “pretty” and they would make it clear that a key element of that happy situation was my amazingly white skin. This made me squirm, needless to say. Going farther along this logic of Batak colorism, Batak families would sometimes line up their children for photographs they had asked me to take, all the while commenting that the darker skinned children were the ugly ones and the lighter toned youngsters were more comely. They were evidently joking but there seemed to be an element of aesthetic conviction there as well (colorism prejudices are found in numerous Indonesian societies). But, I thought to myself: many Indonesian Chinese who lived an hour’s bus ride away in the administrative town of Padangsidimpuan had light skin, yet my Batak acquaintances considered them peculiar-looking, in negative ways. This was puzzling. Apparently, the presumed underlying corrupt character of the “Cino” devalued their whiteness.

I knew all of this on a daily basis during my fieldwork: I was living in the midst of a swirl of racist opprobrium, among Batak adults and elders I loved and admired. Years later when I broadened out the geographical scope of my fieldwork and lived for six months in the West Sumatran town of Bukittinggi, studying the social history of heritage textiles there, I encountered embodied anti-Indonesian Chinese racism once again. For instance, an adolescent daughter of an Indonesian Chinese business owning family told an American undergraduate student I was mentoring that she (the Indonesian Chinese girl) was often harangued and yelled at on the street as she walked along. I have never written about this. Yet, all throughout my career I have often written about the politics of arts such as the Nage gold crown and the Angkola Batak-language novel.

By the 2000s and especially after 2005, writers in the more serious Indonesian-language newspapers were dissecting and even condemning this nation’s history of anti-Indonesian Chinese racism. By then, international and Indonesian scholars were writing the histories and political economy of this ideology (see, for instance, Jemma Purdy, 2006, Anti-Chinese Violence in Indonesia 1996-1999. ASAA Southeast Asia Publications. When former Indonesian President Soeharto’s decades’ long grip on power broke in May 1998 and his regime collapsed, Indonesian Chinese in some large cities were physically and sexually attacked in mob violence. This has drawn recent scholarly attention). But, in my own writings and museum exhibitions – all purportedly such political texts – I myself have said nothing until now about the frank racism of my Tapanuli companions of the 1970s and 1980s. Why this silence? A fieldworker’s reticence to criticize people who have been so friendly and helpful to us? Or, an ethical cowardice on my part? A fault line in American anthropology of that pre-1998 era? Perhaps all of these are causes.

Racialized ideologies and their corrosive, real-world consequences for persons such as Indonesian Chinese individuals sometimes stayed hidden from scholarship during the long Soeharto-era decades (if not from this fieldworker’s own experiences and knowledge). More acknowledgment and analysis of uncomfortable social facts like these are needed. In my own work, in a book manuscript in progress now called “Learning Batak: Encounters with the Angkola Batak Language in Soeharto-Era Indonesia.” I am at last confronting these oversights.

Endnotes

[1] One of the sub-ethnic groups comprising the Batak peoples in North Sumatra.