The Cultural Hybrid in Colonial Java and Pekalongan Buketan (Bouquet) Batik

Abstract in Bahasa Indonesia: Buketan berasal dari kata bahasa Perancis Bouquet yang berarti rangkaian bunga (floral motif), merupakan motif batik Belanda yang dibuat oleh wanita Indo-Eropa di Hindia Belanda pada akhir abad 19. Hingga kini, kelompok-kelompok non-Indo, seperti masyarakat Peranakan Tionghoa dan pribumi, kemudian membuat dan memadukan motif buketan dengan berbagai elemen kebudayaan mereka masing-masing. Maka motif buketan menunjukkan bentuk-bentuk dari hibrida kebudayaan yang kemudian menjadi batik khas Pekalongan.

Permasalahan dalam penelitian ini adalah bagaimana membaca dinamika identitas sosial masyarakat di Pekalongan melalui pembuatan batik motif buketan. Lebih lanjut dikembangkan pada kajian bentuk negosiasi budaya antara lokal dan pengaruh asing yang tampak pada motif buketan.

Produksi dan reproduksi batik motif buketan merupakan proses pembentukan taste, yang dapat dipahami sebagai konsumsi budaya dan dapat dipertukarkan oleh modal simboliknya. Terbentuknya standar-standar baru penciptaan motif buketan melalui mekanisme produksi massal dan modern, berimbas pada pengaruh publik dan merebut wilayah proses artistik pembuatan batik. Menggunakan motode etnografi penelitian ini mengamati pengalaman budaya membatik, khususnya motif buketan pada komunitas yang beragam di Pekalongan. Pembuatan motif buketan dengan demikian menunjukkan kontestasi masyarakat di Pekalongan dalam mengapropriasi dan mengimajinasikan identitas sosialnya.

Abstract: ‘Buketan’, originally from the French word meaning ‘bouquet’ refers to a batik motif which formed the essence of Dutch Batik (Batik Belanda) developed and produced by Europeans of mixed-blood or ‘Indo-European’ women in the Netherland East Indies at the end of the 19th century. Till today, non-Indo societies, such as Peranakan or Indo-Chinese and indigenous people have created and combined buketan motifs with their own cultural elements. As a consequence, buketan represents forms of cultural hybridity that then become a representation of Pekalongan Batik in Central Java, Indonesia.

The subject matter of this article is how to understand the dynamic of social identity in 19th century Pekalongan society through the creation of buketan batik. Furthermore, this research perspective is expanded by a study about forms of cultural negotiation from local to foreign or outsider influence as shown in the buketan.

The production and reproduction of buketan batik motifs are processes of forming ‘taste’ which can be exchanged by its symbolic mode. The emergence of new standards of creating buketan motifs, either through technical or motif innovation via mass- and modern-production mechanisms affected and occupied the artistic process of creating batik. The research for this article uses an ethnographic method by observing cultural experiences in creating batik, especially buketan, by numerous communities in Pekalongan, Java. This article proposes that the creation of buketan shows social contestation in Pekalongan in appropriating and imagining social identities.

Citation: Melati, Karina Rima. “The Cultural Hybrid in Colonial Java and Pekalongan Buketan (Bouquet) Batik.” The Jugaad Project, 20 Sept. 2019, thejugaadproject.pub/the-cultural-hybrid-in-colonial-java-and-pekalongan-buketan-bouquet-batik [date of access]

‘Buketan’, which originally comes from the French or Dutch word meaning ‘bouquets’, refers to the batik motif which was an essence of Batik Belanda or Dutch Batik developed and produced by Indo-European women in the Dutch East Indies (or East Indies) at the end of the 19th century. Accentuating beauty and softness in its decoration, the motif quickly enticed customers. Afterwards, neighbouring societies such as Chinese and indigenous people created and combined buketan motifs with their own cultural elements. As a consequence, the buket motif represented forms of cultural hybridity in Pekalongan, a community well-known for its batik artistry in Indonesia Batik. In time, this motif as it was produced and developed in an assortment of forms and clothing variants became exclusively known as Pekalongan batik.

The objective of my research is to understand the social identity dynamics of Pekalongan society through the creation of batik buketan motifs (floral motifs). This article discusses how the production of buketan batik in industrial system and modern institutions has shifted the mechanism of traditional batik production in Java. Previously, Javanese women only made batik for their own consumption. Butekan batik also holds a special symbolic meaning of honorable Javanese culture, demonstrated by its display in the Javanese Palace. The buketan can also be interpreted as an example of a western idiom for an object of desire during the colonial era (1890 - 1940). Therefore, the buketan motif presents opportunities to study the forms of cultural negotiation between the local and foreign.

I argue that the production and reproduction of batik with buketan motifs are processes of forming "taste", drawing from Pierre Bourdieu's ideas of cultural consumption as a type of exchange through symbolic modes. Exchanges are in the form of modernity and exclusive symbols enclosed in the craftsmanship and exotica of buketan motifs. Meanwhile, the emergence of new standards of creating buketan motifs also created an accompanying cultural industry (Walter Benjamin 1936). Through its process of mass production in Java, batik became a fundamental part of popular culture while overriding the traditional values it represented. My research included ethnographic methods and the observation of cultural experiences in batik production, especially buketan motifs made by numerous communities in Pekalongan on the coast of North Java.

Figure I: Buketan batik motif made by local entrepreneur in Pekalongan (Source: Private documentation)

Through my research I propose that the creation of the buketan motif demonstrates not only how new motifs are created but how societies contend with, and contest, issues of aesthetics, materials and labor in appropriating and imagining their socio-cultural identities. This process of contestation allowed Pekalongan society to negotiate between consumers/markets and their relation to the formation of “taste” as a social habitus (Bourdieu 1977). As a result, the “taste formation” of buketan motifs revealed that there was a dynamic, performative history and process behind the creation of this batik style.

The History of Buketan Motifs

The existence of batik in Indonesia is increasingly confirmed through the material culture of the Mataram kingdom in the 16th century in the form of fabrics with geometrical motifs that became manifestations of the royal symbols of Javanese courts and cultures. However, each batik region in Java, Indonesia, has a motif that became its specialty. The batik motif was developed based on the characteristics of regional traditions, beliefs, understanding, the development of Pekalongan people's contestation, social life and even attests to the “euphoria” of the Indonesian batik industry that took place in that area.

At the same time, batik motifs outside the palace, referred to as north coastal batik motif or passisir, were developed dynamically by its society. Motifs were drawn from daily life and the environment in which they lived. Pekalongan, for example, is one of the northern coast regions of Java that developed its own coastal motifs. At first, Pekalongan batik motifs were not much different from the batik motifs of the palaces in Jogjakarta and Solo. This is because historically Pekalongan was 'discovered' when the great sultan of the Mataram kingdom came to power (Pepin van Roojen, 2001: 19). But then the motif developed more organically, inspired by nature, activities and immigration, resulting in non-geometrical designs by local people.

The period of batik as a commercial industry in the Javanese coastal region started from the latter half of the 19th century until the 20th century. At that time a new group of batik makers emerged, mainly from migrant groups such as Indo-European or European mixed blood and Indo-Chinese, who are known as Peranakan Chinese. The term Peranakan Chinese refers to an ethnic group descended from Chinese settlers from the southern provinces who came to the Malay archipelago and Indonesia. Initiated by the Indo-European group, Pekalongan became the center of development of the batik industry. In their batik business, ‘Indos’ as they were called, made motifs by displaying European idioms which were later referred to as "Batik Belanda" or Dutch Batik (figure II).

Figure II: Batik Belanda motif (Source: Harmen Veldhuisen “Batik Belanda 1840-1940 Pengaruh Belanda pada Batik dari Jawa Sejarah dan Kisah-kisah di Sekitarnya”)

One of the motifs that became the essence of Batik Belanda is the 'buketan’ motif or floral motifs in the form of flower arrangements that also have a variety of decorative figures such as birds, butterflies, peacocks and swans. The use of decorative styles of flowers is a stylization of naturalist forms associated with the Art Nouveau movement that developed in Europe from 1890-1930. This style refers to the penchant for collecting plants as one of the hobbies in Europe, so that artistic illustrations relating to plants were also developed. Since the 17th century, flower arrangements have become the attribute of gifting and exchange between diplomats and missionaries to the Eastern region.

In addition, since the mid-19th century the study of botany became a popular recreational activity in Europe and influenced the development of batik belanda. With the existence of the Art Nouveau movement in the early 20th century, the Dutch government, (which at that time also had colonies in the Indies) encouraged Dutch students to write about batik with references to naturalist-style batik as part of the art movement (Pepin van Roojen, 2001: 22-23). The Dutch were fairly supportive of the batik industry, and even exported the cloth to Europe in modest quantities. Their interest increased in the early 20th century, facilitating an exchange of ideas between batik makers in Java and the proponents of a Dutch brand of Art Nouveau, the new and revolutionary decorative style of the period in Europe. Dutch scholars were also responsible for a number of important publications on batik, which remain among the most valuable reference works in this craft. The emergence of bouquet designs on batik motifs in the Indies began since the Indo-European and Peranakan (mixed-race) communities produced batik that was free of symbolic Javanese batik motifs, such that the European motifs, including buketan, became a form of a “free style” statement. Buketan motifs were made for the Indo-European community, especially from various sources such as magazine illustrations, European planting books, Art Deco-style wallpapers (Harmen Veldhuisen and Kahlenberg in Robyn Maxwell, 1993: 385)

The bouquet motif was originally illustrated with flower arrangements that flourished in the Netherlands or Europe, such as roses and lilies, including flora that were not, or rarely, found in the Indies such as tulips, grapes and chrysanthemums. The making of the buketan motif was first carried out by the Indo-European woman, Mrs. L. Metzelaar, who opened her batik business in Pekalongan in 1880. (Indo-European women such as Metzelaar initiated the next step in entrepreneurial batik production in Java and were followed by other batik entrepreneurs who supervised a group of female batiksters (batik makers), hired to draw wax patterns in the backyard of their compounds.) The bouquet motif was originally in the form of a simple flower arrangement (figure V) which was arranged repeatedly on the sarong body (Herman Veldhuisen, 1993: 79). The next bouquet motif was made and imitated by other Indo-European women as part of the Batik Belanda trend. The buketan motif was met with popularity when produced by Elizabeth Charlotta van Zuylen (known as Eliza van Zuylen), and was commonly identified as a combination of autumn and spring flowers. Her design, repeated buketan in kepala (head or edge of sarong or hip wrapper) and badan (body of the sarong) (figure IV), is still known today as batik Pansellen and was copied by Chinese batiksters and became part of a distinct Nyonya-style sarong (figure III), nyonya referring to the honorific title attached to a foreign married lady.

Figure III: Nyonya Saroong with buketan batik motif with encim kebaya (Source: private documentation from Peranakan Museum, Singapore)

The Chinese Peranakan community were also involved in the batik business after many had become traders of batik and batik-making materials. Around 1910 the issuance of a new regulation by the Dutch government named Gelijkgesteld which meant "equality" for Chinese groups or Peranakans with the upper class European groups (Inger McCabe Elliott, 2004: 120) spurred further change in adapting Indo-European batik motifs of the buketan variety. The flowers drawn began to show the distinctiveness of Chinese culture such as lotuses, chrysanthemums and tulips. In some batik, people began using decorative items that fit Chinese mythology such as Phoenix birds and banji (swastika) decorations. Furthermore, the motif of the typical Chinese Peranakan bouquet was also applied to a background filled with cocohan or dotted shaped ornament such as a grain of rice.

Figure IV: Nyonya Saroong with buketan batik motif with encim kebaya (Source: private documentation from Museum Textile, Jakarta)

Subsequently, the buketan motif proved increasingly popular and flexible, and adapted to various floral motifs. The motif that was originally in the form of a flower arrangement was then "broken" into smaller sequences or just indicated as flowers and leaves. The new derivative motifs may not even appear as a flower arrangement or buketan. Some of them are occasionally only used as a complement to other batik motifs. In addition, various changes were made in the 1970s when, following government regulations to meet high demand, buketan motifs were simply printed to long fabrics or skirts (sarongs) for fashion as clothes that were sewn and ready-to-wear. These ‘fake batiks’ included shirts or blouses, dresses, t-shirts or long dresses, jackets, skirts, negligees and so on. The buketan motif was then applied based on contemporary forms when the batik was made. In addition to fashion, buketan motifs are also inspiration for decorations on household items such as sheets, bed covers, tablecloths, napkins, etc., and even in interior products, handicraft items, and accessories, including materials other than cloth.

Cultural Hybridity and the Making of ‘Taste’

The production and reproduction of buketan by Indo-European women was followed by Chinese and indigenous Peranakan communities, demonstrating the existence of these motifs as part of a form of cultural hybridity between local and foreign influences. Pekalongan in this case became a 'field' or space where subjective relations created a system where social positions were interconnected with one another. This system of inter-subjective relations in turn shaped the buketan batik motif as a symbolic system.

I suggest that the process of forming ‘taste’ with the buketan motif is better understood through the analysis of cultural consumption. Batik buketan motif represents the taste of Pekalongan community that has an association with certain cultural products, which is a cultural hybrid. This according to Pierre Bourdieu (1977) can be explained through its habitus, meaning that people from certain groups express their taste for motifs by making, using, or even collecting the batik buketan. To cite one example, symbolic value permeated the buketan motif via the exclusivity of the maker’s craftsmanship and stamp such as Van Zuylen. This value derived its prestige as a mark of sophistication by being associated with the skill and brand of an ‘Indo’ producer and simultaneously legitimated the creation of a corresponding taste in society. This can be understood as the ‘object of desire’ which created a common consensus as to what was to be the character of Pekalongan batik. So much so that in Pekalongan, especially in the area of Kedungwuni, the term ‘Buket’ has come to stand for the drawing of any batik motif, not necessarily the buketan motif.

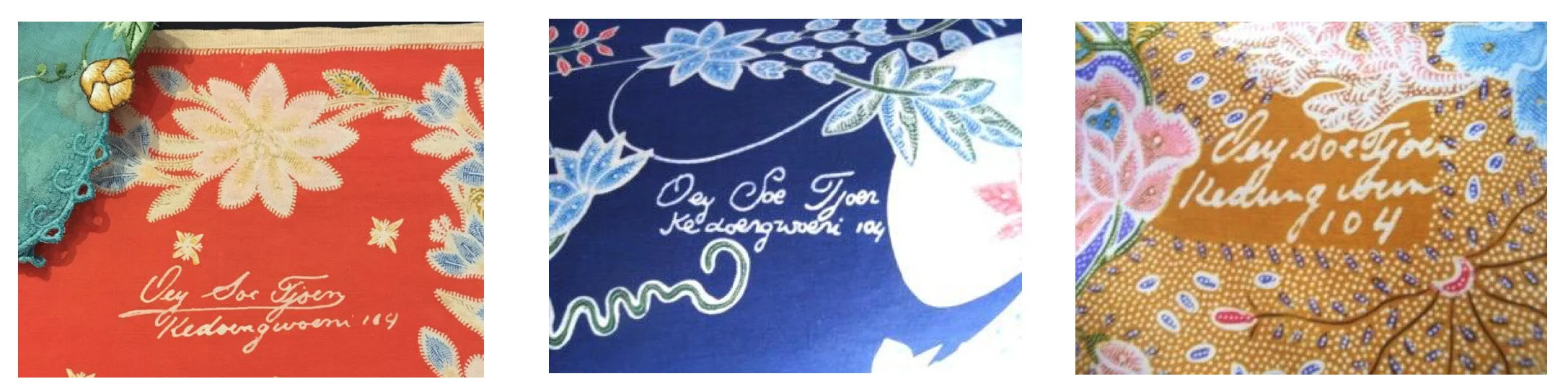

Figure V: Buketan batik motif in sarong (above) and long cloth or kain panjang ‘pagi-sore’ arrangement (Source: private documentation Oei Soe Tjoen Batik, Kedungwuni, Pekalongan, Central Java)

To fully understand the society in which batik makers like Van Zuylen became prestigious, we have to also consider the social hierarchy of the time. The initiators of Batik Belanda or Dutch Batik were Indo-women or mestizo who came from mixed marriages and were stratified in the lowest layer in European society in the Indies. This group’s major social dilemma was gaining acceptance with the local European community. At the same time, they had the desire for recognition as part of the Indies community who were active in local indigenous culture without submitting to the establishment (court and associated values) of traditional Javanese batik. In other words, the Indo community showed at least two dynamics that complemented each other: the existence of possible democratization in existing power relations between mestizo and Europeans and an inequality of taste with traditional batik or other coastal batik regions. Therefore, Batik Belanda could be said to have developed an agenda to break the regime of traditional Javanese batik and its association with the traditional courts.

In the colonial context, the creation of buketan shows the collapse of dichotomy between colonizers and colonized; or between indigenous and non-indigenous culture. Batik, which was previously associated with traditional Javanese culture and the power of the sultans’ courts, could no longer be maintained as an exclusive, static entity because popular culture moved the art form in a hybrid direction born out of negotiation of power and roles. Indo women who were included in the framework of batik’s ‘exoticism’ were not directly involved in the process of making batik. Instead they ‘only’ initiated the design and recruited local residents to do batik in their homes as laborers. Those Indo-European women who became owners or entrepreneurs perpetuated batik motifs with European visual forms that were far from the batik maker’s own imagination. In running the business, they imposed a division of labor that emphasized the ‘capitalization’ of batik culture. It also shows an ambivalence towards the notion of a cultural identity for batik, i.e. as a skilled art born out of certain socio-cultural conditions, because the resulting commodification of batik decreased the authenticity of ‘batik culture’ and left it purely to the logic of the market. The concept of hybridity in the representation of colonial identity thus reveals an active moment, when people were involved in the negotiation of cultural identity through commerce and creativity.

In the boom in production of buketan, from 1880 until 1910, there was a pattern of market penetration that shaped the tastes of members of the Indies’ community. In the following years, the buketan batik motif was internalized and reproduced by most coastal batik entrepreneurs from various circles, even long after the Dutch and European occupations ended in the Indies (later Indonesia). After Indo-European women, Chinese Peranakan and local residents continued making buketan batik motifs with the nuances of their respective cultures.

Figure VI: The batik producers put signatures bearing the name of the city of Pekalongan as a form of authentication that catapulted the name of Pekalongan (Source: private documentation from Batik Museum, Jakarta, and Oei Soe Tjoen Batik, Kedungwuni, Pekalongan, Central Java)

The point to be underlined here is that the aesthetic form connoted by buketan is best understood not by defining it as a restricted pattern (i.e. the Javanese batik motif) but as an entity formed through interaction. This development depended on cultural translation through interaction between local and other migrant cultures, which then exchanged and reciprocally developed mutual interpretations of one another. Indo-Europeans broke the hegemony of batik techniques that had been owned by Javanese (especially those associated with the courts) for a long time, while non-European people translated buketan batik motif within their taste-based forms.

Thus, the acceptance of the buketan batik motif in the framework of Javanese batik was through the spirit of interacting, negotiating, and innovating by the agents who processed it. Batik, which even today is associated with the hegemony of Javanese culture, transformed through its encounter with the culture of immigrant communities. Migrants, such as Chinese Peranakan, although a minority, were a well-established community who were willing to participate in utilizing local craftmaking, developed in accordance with their intellect and imaginary.

A study of the history of buketan batik uncovers the ambiguity and dynamism of the development of new forms: first, buketan was about a European motif and yet utilized a Javanese technique. Second, buketan was formed when a type of Javanese culture met another culture (European, colonial, Art Nouveau) formed by Western-European expression. Third, batik buketan was inherently dynamic and ambivalent as it was based on an ‘inequality of taste’ subject neither to the establishment of ‘Javanese batik’ or ‘coastal batik’ (although later it has come to be simplistically classified as coastal or pessisir batik). Lastly, through this interaction, buketan became a symbol of modernity in the Indies and Indonesia. Together these factors could be called a socio-cultural deconstruction of batik buketan culture.

Conclusion

The dynamics of identity of Pekalongan society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was built by the meeting of various tastes which were then commodified by Pekalongan communities. The changes in the form of buketan batik motifs over time are evidence of how aesthetics, formed through the space or context of negotiation, act as a form of cultural hybridity. The process of taste formation in buketan batik shows a change in batik culture both from the aesthetics and the process of making batik. The creation of new meanings of buketan batik motif along with its symbols are best understood as processes that include encounters and exchanges of cultural displays that also adjusted to the market. Buketan batik is now accepted by consumers not only in Pekalongan, but has also spread across Java, Sumatra and as the typical Nyonya sarong of Chinese Peranakan in the Southeast Asia region.

The appropriation of buketan batik motifs by various groups in Pekalongan, Java, is analyzed as the process of merging boundaries to encourage commerce and changes in production of batik. Pekalongan batik entrepreneurs, especially migrants, applied a system of commercialization in batik manufacture: organizing the division of labor, wages, developing batik techniques, coloring and trading. Therefore, the existence of the batik industry in Pekalongan is mainly supported by its craftspeople, modern trading systems, and the innovations of its entrepreneurs.

To conclude, the production and reproduction of buketan batik motif shows how batik production helped Pekalongan people to determine and define themselves and their environment. The creation of the meaning of forms and symbols can be understood as points of meeting and melding of various cultures that occurs continuously in life but is crystalized in forms such as buketan.

Bibliography

Harmen C. Veldhuisen. 1993. Batik Belanda 1830-1940, Dutch Influence in Batik from Java History and Stories. Jakarta: Gaya Favorit.

Inger McCabe Elliot. 2004. Batik Fabled Cloth of Java. Singapore: Periplus.

Pierre Bourdieu. 1977. Outline of Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Pepin van Roojen. 2001. Batik Design. Netherlands: The Pepin Press.

Robyn Maxwell. 2003. Textiles of Southeast Asia, Tradition, Trade and Transformation. Australia: Australian National Library

Walter Benjamin. 1999. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” In Visual Culture the Reader, Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall (eds.) London: Sage Publication.