Timur Merah Project: A Pilgrimage of Narrative, Memory, and Historical Legacy

Abstract

Balinese artist Citra Sasmita writes about her ongoing project “Timur Merah” and its interest in probing the important role of women in the Indonesian literary and artistic canon. She notes that historical archives, classical paintings, and ancient manuscripts in the archipelago (Nusantara) that carefully discuss the role of women are very difficult to access and not well distributed. Sasmita maps stereotypical depictions of women in canonic texts, and in a counter reading of women as leaders and resistors, emphasises heroes such as I Dewa Istri Kanya, Queen of the 19th c. Klungkung kingdom. In the second half of the essay, Sasmita tracks the effects of the indigenous male gaze on women, art and the island of Bali, as it transforms into the Dutch colonial gaze, determining what is “authenticity” and privileging what/who should be deemed valuable in shaping Balinese artistic heritage.

Citation: Sasmita, Citra. “Timur Merah Project: A Pilgrimage of Narrative, Memory, and Historical Legacy” The Jugaad Project, 3 September 2022, www.thejugaadproject.pub/timur-merah [date of access]

Canonical Texts and Narratives of Women in Nusantara

If history was written by ‘hero(es)’ and, by implication, not by women, it sets the stage for a lack of writing in the canonical text(1) about the important role of women, and establishes a patriarchal mentality and perspective. This invisibility of (heroic) women has been taken for granted without question in what is known as the Malay-Indonesian archipelago.

Historical archives, traditional classical paintings, or ancient manuscripts in Nusantara(2) are very difficult to access. Not to mention finding one that carefully discusses the role of women. Knowledge about the stories of women is also unevenly distributed. To find such treasure is like looking for an oasis in the middle of the desert. Thus far, women have always been ornaments or romantic narratives in stories, a badge of glory in kings’ and princes' reigns. As a source of social and cultural history of Indic kingdoms in the archipelago, Kakawin (ancient Javanese poetry) helps us consider (the lack of) a critical approach to gender in analysing themes of war, love, and marriage (Creese 2004). This gap, in turn, shapes what or who is considered valuable in “heritage”.

This reflection is the main reason for the Timur Merah Project that I started 3 years ago, in 2019. Timur Merah, meaning “The East is Red”, is a long-term art project that seeks to trace and reread the history and narratives that exist in the archipelago, especially in Bali. I found that too many canonical texts about historical and cultural inheritance were written by men. Especially by those who had an interest in investing authority and power within the aristocracy and palace elite. These texts have been passed down as legacy in Nusantara since the 14th century, and the women in these texts are limited to a procreative role and/or heavily sexualized (Creese 2004).

In my initial research for the Timur Merah Project, there were limitations of access and comprehension in reading manuscripts written in Ancient Javanese and Balinese. Therefore, I gained an understanding of narrative in two ways. First, by conducting interviews with priests and elders who have inherited this knowledge. Second, through wayang narration(3). Some wayang narratives can be interpreted through Kamasan painting, a painting style or genre developed in Klungkung, Bali, from the 15th century until now. However, Balinese culture practices the Wangsa or caste system, where only the Brahmins have access to reading lontar (palm leaf) texts and literary works in ancient languages. By contrast, the knowledge of Kamasan paintings is accessed more readily and in different way. Kamasan painters who live near the center of the Klungkung royal government are required to depict the pakem (cultural code)(4) of the wayang and its composition in the painting. Just as a puppeteer composes an image based on the storyline, these drawing experts of Klungkung have inherited and will pass on a practice of narrative as the ability to ‘read’ texts from generation to generation. Thus, even as these paintings relate to/invoke canonical texts, they influence a broader cultural understanding of what counts as ‘text’, and the aesthetics and experience of reading.

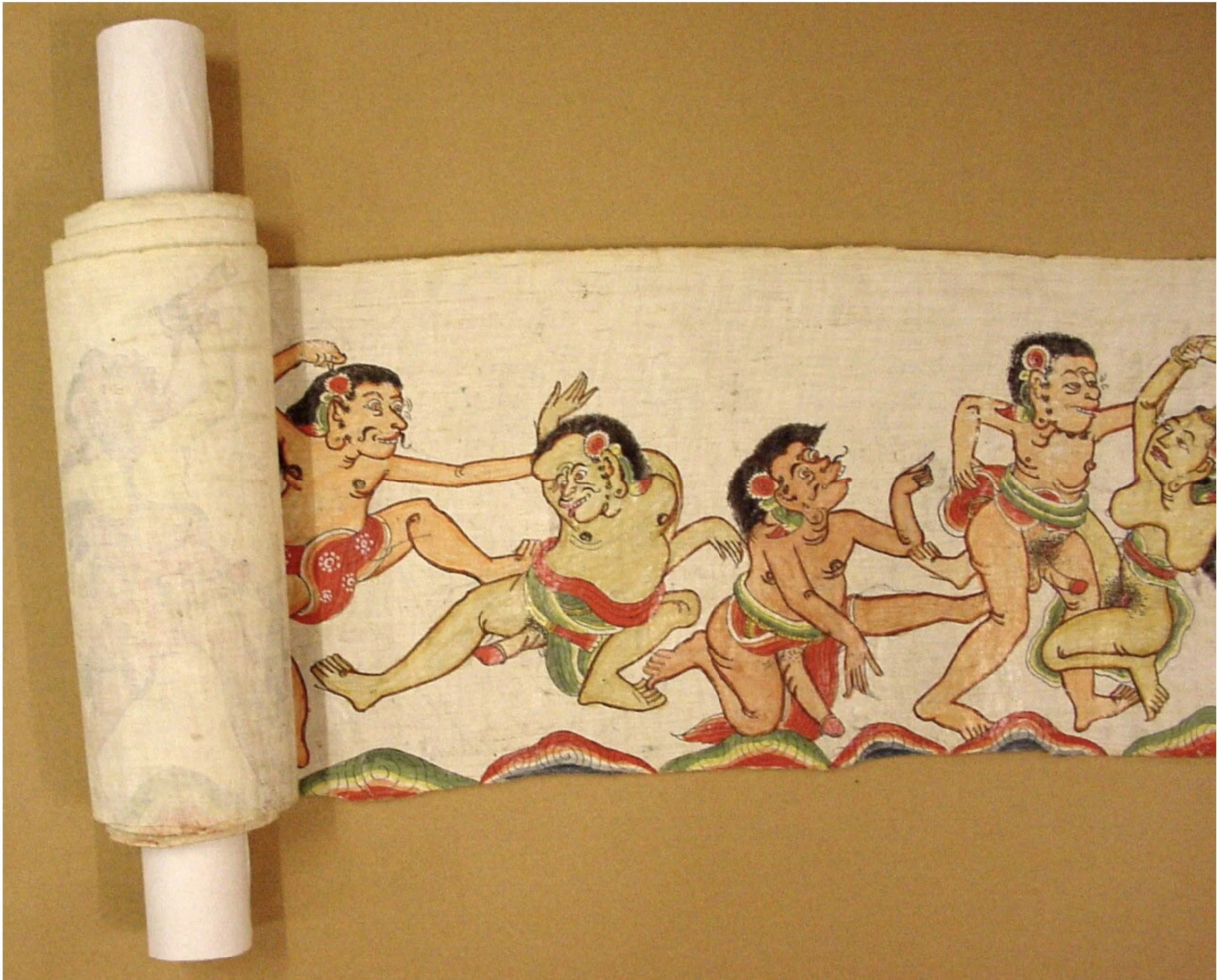

The story of Panji, a hero’s journey of the princes of Kahuripan in East Java, is one of the canonized scripts that was written out in great detail in the 12th century. The story tells of the princes’ embarkation on an expedition and military invasion to expand their royal territory as well as their marriages with princesses and beautiful women of the lands--trophies from the lands they invaded. In addition, erotic visuals are often used to illustrate the story of Panji and its gendered attitude towards women wherein the princes of Kahuripan were known to collect wives. Women’s bodies are thus depicted as sensual entities personified as nature, such as ripe fruits and exotic scenery, and seduced and dominated by forces of masculinity.

Image 1. Anonymous, Kamasan, Bali, 23.5 X 397cm, 1961. A historical depiction of Panji Malat, the kings of Kahuripan and Kediri arrived at Gegelang and entered the abode of the princes with the king of Gegelang. Permanent link to this image.

Image 2. Anonymous, Kamasan, Bali, 84.3 X 84,3cm, 1984. Erotic illustration from the Panji epic. Permanent link to this image.

In my understanding of eastern erotica, sexuality is not only described as a procreative agenda for the survival of humankind but lingga (penis) and yoni (vagina) are interpreted as spiritual forces. In some of the rituals, these symbols serve to protect humans from unwanted energies. Hindu rituals, such as Nyegara Gunung,(5) in Bali, are still anchored in this gendered cosmology.

Image 3. Anonymous, Kamasan, Bali, 925 x 28 cm, 1940, Ider-ider (long painting) depicting mythological and erotic scenes. This painting is usually installed around the ceiling of Balinese architectural buildings/pavilions. It consists of several sequential scenes which are separated from each other by a diagonal line of mountains and visuals of clouds. The left half of the canvas illustrates male and female figures who seem to be talking to each other. At the end of the story, one of the women is taking revenge by conquering demons with her genitals. Collected by Georg Tillmann. Permanent link to this image .

The Panji epic is legendary and was once a big commodity, commissioned by kingdoms in Bali. In addition to the function of decoration for royal and temple architecture, paintings of the Panji epic also played an important role in education, especially in creating military strategies and training the royal troops for combat.

Another viewpoint regarding women in the wayang narrative of Kamasan paintings is the figure of a monster with evil powers. Knowledgable women are associated with magical powers that can spread the plague, terror, and catastrophic death, as is known in the famous 12 century Calonarang story. It is said that Calonarang was a widow and powerful in black magic. She worshiped Goddess Durga, sakti(6) of the Lord Shiva. She and her followers often harassed the farmers, spreading terrible diseases that caused sudden deaths. Calonarang was defeated after her spell book was stolen by her son-in-law, Bahula. He was a student of Mpu Baradah who was sent by King Airlangga to stop the terrors created by Calonarang. Binary opposition in the Calonarang story places women solely as antagonists while men are the heroes.

If we delve into the narrative, the concept of sakti in the Calonarang text is one of the crucial markers of the divine in feminine nature. Sakti stands as a spiritual resource and power that supports the deity’s life partner. Sakti symbolizes the power dynamic of a heavenly mother, i.e. the guardian of the universe and the caretaker of life rather than a destructive force as is usually depicted.

Image 4. Anonymous, Kamasan, Bali, 136 x 171 cm, 1915. A scene of Calonarang and her followers transformed into cruel figures with her magical force. Permanent link to this image .

By interpreting these findings, I am aware that I take part in the broader discourse of narratives that we have inherited in Nusantara. As an artist, I make women central characters and protagonists in my paintings to challenge the fixed, single way of reading and interpreting narratives about women. I often transform masculine deities or mythological figures with supernatural powers, commonly found in old Kamasan paintings, to female figures. In work, “Timur Merah Project I; The Embrace of My Motherland” (2019), (Image 5) I interpreted the story of a famous chronicle in Nusantara, depicting the creation narrative and the genealogy of kings in Java. I depicted God, prophets and the early humans as female figures. This depiction serves as a negotiation exercise for me, as an artist, with the people of the Nusantara community and/or people who appreciate art to simultaneously consider history, canon texts, and a cultural heritage that pre-dates colonialism. What if those texts had featured the important roles of women? Would discrimination toward women continue to this day? “Timur Merah Project I” presented this narrative at the Biennale Jogja 2019, in Yogyakarta.

Image 5. Timur Merah Project I; The Embrace of My Motherland, 5 panel traditional Kamasan canvas, 90 x 400 cm, the text on the floor was painted using turmeric powder.

My other work, “Timur Merah Project V; The Verge of Mortal Ground” (2021), was a painting installation (Image 6) I created during the pandemic. The work was exhibited at ARTJOG Resilience 2019, an annual art event in Yogyakarta. The theme was of the endurance of artists working during the pandemic and I responded to my reading of Calonarang. Calonarang recounts the tense situation of an outbreak and spread of a mysterious disease that caused everyone to lock themselves at home—what we know today as kuncitara (lockdown). The artwork was hung in the middle of a room and installed in a circular formation. The installation intended to entice the audience to step inside the painting's circle and reflect on a series of visual stories where the epidemic spread with no cure to be found, thereby causing human mobility to come to a halt. It is to be noted that at the same time as the Calonarang story, texts on medicine and/or medicinal plants (usadha) were also widespread, a situation that reminds us of how solutions for modern human problems could be derived from Eastern knowledge and wisdom.

Image 6. Timur Merah Project V; The Verge of Mortal Ground, 60 x 580 cm, traditional Kamasan canvas, 2021 ARTJOG Resilience 2020, Yogyakarta.

From the Canonic Male Gaze to the Colonial Gaze: Creating a Counter-narrative and Reading of Balinese History

Image 7. Timur Merah Project VII; Divine Comedia, 90 x 600 cm, traditional Kamasan canvas, 2 antique pillars, 2021, ARTJOG Time To Wonder, Yogyakarta.

“Divine Comedia” (2021) (Image 7) is a continuation of “Timur Merah Project VII”. It focuses on the reinterpretation of the Bhima Swarga script, which is an archetype of the same story as the epic poem La Divina Commedia (1320 CE) by Dante Alighieri. Bhima Swarga tells the story of Bhima's journey to the underworld to save Pandu and his wife from the torments of hell and guide them to the upper world. In this quest, Bhima witnessed spirits being tortured and punished for their karma (destiny) during their lifetime.

The Bhima Swarga manuscript was painted on a ceiling of the Kertha Gosa (Hall of Justice, Image 8) in Klungkung. Now a museum, Kertha Gosa was once the place where kings conducted trials and judgments against criminals. The kings sentenced thieves, people in debt, or outlaws based on their interpretation of the ceiling paintings. Some were sentenced to death and exiled to Nusa Penida. But the most common conviction was enslavement.

Image 8. Ceiling of the Kertha Gosa (Hall of Justice) in Klungkung, Bali. Photo by author.

These historical facts have broadened my hypothesis regarding the complex problems of patriarchy and social injustice towards women in Bali. Bhima Swarga's painting led me to explore the history and excesses of colonial remains in Bali. These colonial remains influenced the religious rituals, arts, and everyday life in Bali. The impact is apparent to date as the dark side of Balinese tourism, an outcome of Balinization or Baliseering, an “ethical politics” constructed by the Dutch in 1920.(7)

The enforcement of unilateral policies by the Dutch in the 19th century encouraged native resistance efforts. The Dutch colonial mission was to control Balinese ports for their economic interest. At that time, the most prosperous Badung kingdom (1788-1906 CE) ruled over three port areas, namely Sanur, Benoa, and Kuta in southern Bali. These areas attracted many foreign traders as well. The Badung kingdom had a trade arrangement with the Dutch that gave them access to ports in return for weapons, platinum, and gunpowder supply to strengthen their military base. This lasted until the Dutch broke this agreement by smuggling slaves from Bali, one of the many reasons for the kingdoms in Bali to organize a resistance movement. The Klungkung rulers led as junjungan/sesuhunan (Bahasa Indonesia: the head) of the Balinese kingdoms who chose to fight together to the end.

An influential resistor was I Dewa Agung Istri Kanya, a Queen from the Klungkung kingdom (1814-1878 CE). She is the only female author to be found in ancient literary records since their circulation in Nusantara in the 9th century. Dewa Istri Kanya translated ancient Javanese poetry into ancient Balinese as a propaganda medium for the Balinese people, and literature and culture under her formed part of the resistance. One of her poems, Prelambang Bhasa Wewatekan, was considered erotic because it uses tantric arthalamkara (symbolization) which is actually a record of events, war strategies and memoirs about the behavior of the Dutch in Bali (Naryana 1987) and tantrism, an ancient belief before Hinduism and Buddhism, greatly influenced the nuances of eroticism in her poetry.

In several fragments of the Prelambang Bhasa Wewatekan, I Dewa Istri Kanya writes about her resistance to Dutch colonialism, reversing the gaze as it were to “read” the men in power, as for instance, in the following poem:

Byatitan sang aneng Bahtawi greha mangaran Gubernur Jendral Open,

Hindrik Huskus Jakupman maka muka hiniring Hendralas den kinonkon,

Wāgmeng cestottameng inggitakara nguniweh solah ing rāja gostiya,

Tan manman bhaktiya nāthā ticaya jaya jayeng çatru deniyopayasih

Miwang sope rotya saprang wipatisa pinangan Sangwan ing mārgā sangkep,

Tingkahning rāja konkon sama rasuk irasuk purna ring angga mulya,

Mungtab kapyah rinenggeng emas ataputapung tejan ing kwas ri bahwa,

Wwanten tan çuciya yar ton waja putih abekil uçwasabo wigāndha

Translation:

We miss (the above and told) the person who was in the palace in Betawi named Governor General Open,

As a leader is Hendrik Huskus Jakupman and followed by Hendralus,

Clever in speech manners and with hand gestures, especially when talking to the king,

Do not hesitate to respect the king and have defeated the enemy by the trickery of friendship,

(Naryana, 1987, 113)

Image 9. Photo of Balinese and Papuan Slaves from the rulers of the Buleleng kingdom, source probably by I van Kinsbergen, 1865. Permanent link to image.

The association between Bali and the Netherlands started with the first Dutch ship landing in Kuta in the mid-16th century. Since then, the political relationship between the Dutch colonials and the Balinese kings developed through commodity practices such as the slave trade. From 17-19th century Bali was the biggest shipper of slaves. About 2,000 Balinese were shipped every year to Batavia (the capital of Dutch East Indies, now Jakarta), South Africa, and the islands of the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Balinese women were famous for their beauty, work skills, mastery of playing musical instruments, and expertise in traditional medicine. The low castes, widows, and orphans were the most vulnerable groups and targets of the slave trade (Tisna 1935).

Another important historical event was the Puputan war in the Buleleng kingdom in the 19th century. It was an uneven battle wherein the Dutch killed the Balinese with guns and cannons while the Balinese formations and their kings fought with keris (daggers) and bamboo spears, ultimately ending their own lives in a mass suicidal event. This resulted in political victory but moral defeat for the Dutch colonizer. The end of the Puputan war in Klungkung (1908) was the turning point for Dutch colonialism. The Dutch turned their military aggression into the ethical politics of Baliseering, a strategy of cultural diplomacy to repress the rise of the nationalists and the Islamic groups in the Java peninsula (1908-1928 CE). The momentum of the movement reached its peak with the founding of Sumpah Pemuda (1928).

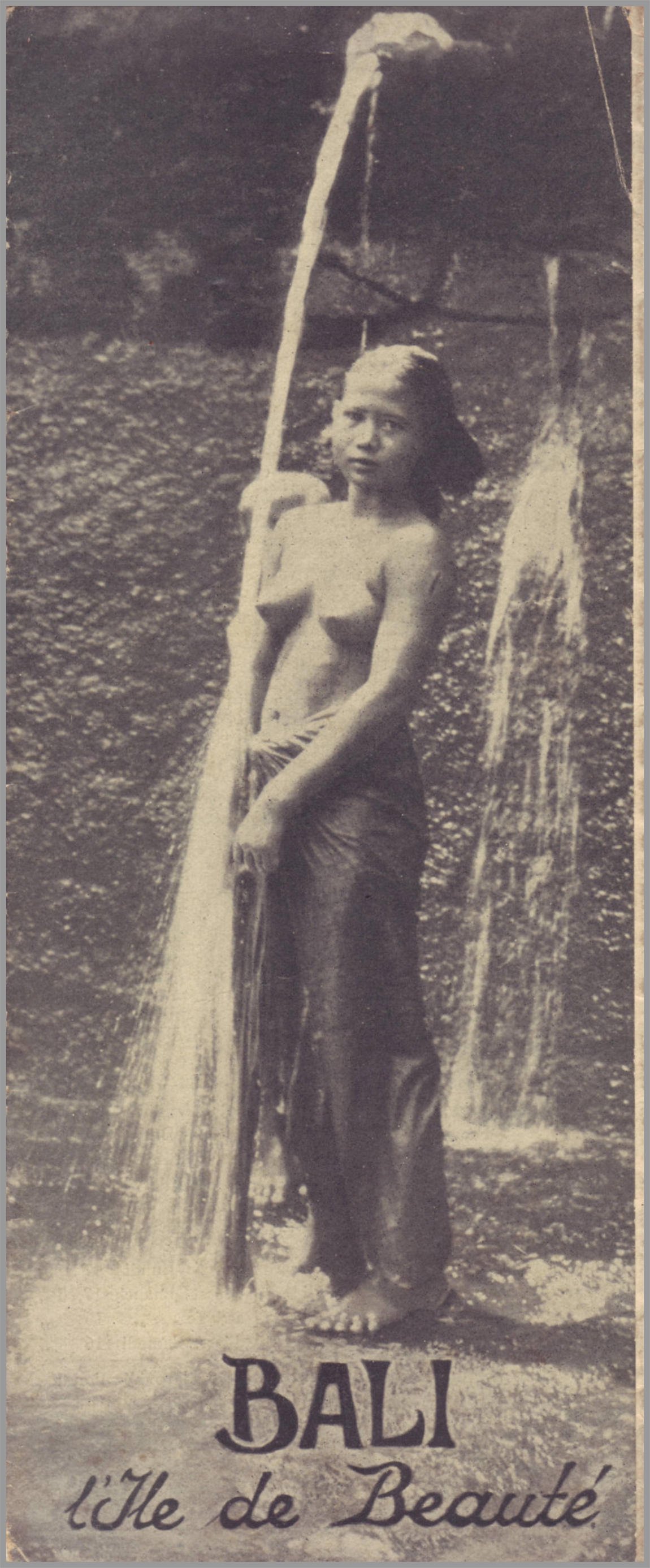

Image 9. Bali Tourism Brochure Cover 1929-1930. Permanent link to this object.

Baliseering politics began to be implemented in Bali (1920) after Puputan Badung (1906) and Puputan Klungkung (1908) through new practices including art, anthropology, photography and film-making. Europeans and Americans visited the island and recorded the natural landscapes and lives of the Balinese people from an exotic and romantic point of view, obscuring in the process, Dutch atrocity against the Balinese. Some European artists who came to Bali were, and still are, lauded as major contributors to the development of modern art in Indonesia and Bali including Walter Spies from Germany, and Rudolf Bonnet and Arie Smith from the Netherlands.

Baliseering's mission was to establish an ‘authentic’ Bali in terms of culture, religious rituals, identity and social class (caste), a feudal and traditional control system that occupied Balinese society from modernity. Educated Javanese nationalists argued that the Dutch wanted to keep Bali as a “living museum”, and remodel Balinese culture in a romantic image that appealed to outsiders, but not to Balinese interested in self-determination (Robinson, 2018: 48). In education policy, Baliseering focused on visual art, traditional dance, sculpture, music, traditional Balinese languages, eliminating other knowledge such as world history, mathematics, and foreign languages (Malay, Dutch and English).

This perspective can be traced to the way the Dutch centralised art in Ubud and passed on Western perspectives and techniques to Balinese artists, changing the paradigm of art in Bali from communal activities, making offerings and decorating religious rituals to becoming more individualistic and commercial. Through this “ethical politics”, the Dutch implied a dichotomy in the classification of high art and low art. The ‘high’ art was the Pitamaha, a group of artists under the shadow of the Dutch. The ‘low’ art refered to those artforms/artists connected with rituals and narrative heritage. This division of high and low could be seen in several other colonised parts of the world, even as an ostensibly ‘static’ authenticity demarcated the real Bali and served to delineate and emphasise the dynamism and originality of modern art. Through Baliseering the Dutch shaped Bali as an exotic tourist center in the world with portraits/posters of topless Balinese women(8). Simultaneously, Balinese were framed as uncivilized islanders (Hanna 2004: 23).

One of the fragments of “Timur Merah Project I” (Image 10) interprets the traumatic experience of Balinese ancestors from the arrival/invasion of Europeans in Nusantara in the 15th century. Two centuries before, in the 13th century, the Geguritan Kebo Iwa text enclosed the prediction of their arrival. Patih Kebo Iwa from the Bedulu Kingdom in Bali cursed Patih Gajah Mada from the Majapahit kingdom when his kingdom was defeated. He said that the mission of expanding Nusantara by overthrowing many kingdoms would fall apart when the white people came. I would say that old manuscripts cannot simply be considered fictitious or only poetic. Prophecies and historical facts can also be a way to read omens although elites politicise it for their own benefit.

Image 10. Timur Merah Project I fragments; The Embrace of My Motherland.

The Timur Merah Project is an embodiment of my resistance to a Balinese cultural heritage that is heavily influenced by colonialism and, now, globalization. The Balinese landscape is described and represented as exotic and noble, and continues to be the background for various writings and readings of history, art, and culture. This depiction is also used to glorify foreign painters and artists who live in Bali with great entitlement and privilege. Foreign painters, artists and scholars hold important positions in Balinese culture instead of Balinese artists and people. This is a form of exploitation that justifies itself by holding the Western world, its values and ideals as the standard. Indeed, counter-narratives to colonial inheritances and the neo-colonial gaze are urgently demanded. My art and research are an effort to make such contributions and demonstrate the possibilities of counter-discourses.

Notes

1. Canonical text refers to texts that are passed down from generation to generation and become authoritative sources of standards.

2. Nusantara is literally translated as the archipelago. Nusantara does not mean Java or Indonesia. In the geopolitical context, the Republic of Indonesia existed after independence. Thus, the archipelago refers to the mapping of the distribution of texts in the trade routes that connect Bali and Java with other regions in Southeast Asia.

3. The wayang narrative, apart from developing into a shadow puppet show, is also part of oral tradition and illustration of Balinese traditional painting.

4. Pakem refers to a cultural code that is omnipresent in various forms of everyday life. In this context, pakem is how wayang should be presented and depicted ideally so that the essence can be transferred properly into the painting. This process plays a role in the repetition of narrative that can be taken for granted. This idealization is naturalized and creates complex tension in cultural practice.

5. Nyegara Gunung is one of the cremation ritual processions in Bali. Nyegara means “the sea” and symbolises the yoni, and Gunung means “mountain”, symbolizing the lingga. Processions to both sea and mountain are considered paths for ancestral spirits to enter the unseen world.

6. Sakti refers to life partner in Sanskrit as well as a form of power. Sakti is a balancing partner, like the merge of two magnet poles.

7. The Dutch began their first invasion in 1846 in Buleleng after the Balinese Kings rejected the trade agreement and rejected the abolition of the law "Tawan Karang" (the law enforced in ancient Balinese kingdoms in seizing boats and ships stranded in Bali) which was considered detrimental to Dutch trade (1841-1845). The Dutch invaded Bali for 102 years and ended in Puputan Klungkung (1908)

8. See Mohan (2019). “Rock, Cloth and Scissors” https://www.thejugaadproject.pub/home/citra-sasmita

References

Creese, Helen. 2004. Woman of the Kakawin World: Marriage and Sexuality in the Indic Courts of Java and Bali. Bali: Pustaka Larasan.

Hanna, Willard A. 2004. Bali Chronicles: Fascinating People and Events in Balinese History. Hongkong: Periplus Edition.

Mohan, Urmila. 2019. “Rock, Cloth and Scissors - Archetypal forms by Balinese Artist Citra Sasmita.” The Jugaad Project, thejugaadproject.pub/citra-sasmita, accessed 28 August 2022.

Naryana, Ida Bagus Udara. 1987. Terjemahan dan Kajian Nilai Pralambang Bhasa Wewatekan Karya Dewa Agung Istri Kanya. Bali: Proyek Penelitian dan Pengkajian Kebudayaan Bali Direktorat Jendral Kebudayaan Departement Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

Noorwatha, I Kadek Dwi. 2019. Naranatha-kanya: Jejak Sejarah Dewa Agung Istri Kanya dan Kebangkitan Seni Kerajaan Klungkung Abad ke-19. Jakarta: Direktorat Sejarah Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

Robinson, Geoffrey. 2018. The Dark Side of Paradise: Political Violence in Bali. New York: Cornell University Press.

Tisna, Anak Agung Panji. 1975. Ni Rawit Ceti Penjual Orang. Bali: Lembaga Seniman Indonesia.

Wijaya, Nyoman. 2013. Puri Kesiman: Saksi Sejarah Kejayaan Kerajaan Badung. Jurnal Kajian Bali Volume 03, Nomor 01.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dayu Ajeng Anggrahita for translation assistance and Urmila Mohan for editing this essay.