Intimacy 2.0: Guru-Disciple Relationship in a Networked World

Citation: Lazar, Yael. “Intimacy 2.0: Guru-Disciple Relationship in a Networked World.” First published in Jugaad: A Material Religions Project, 15 Apr. 2019. Republished in The Jugaad Project, 8 Jul. 2019. thejugaadproject.pub/home/intimacy-20-guru-disciple-relationship-in-a-networked-world [date of access]

Figure 1: Blessings from Sadhguru. Isha USA, email to author, May 2, 2017.

After completing the Inner Engineering program from “Isha Foundation”, I received an email with a handwritten note from Sadhguru—the founder—blessing me on being initiated into his movement and into a close relationship with him (figure 1). “I am with you in all that you are. May you know bliss. Much love and blessings. Sadhguru.”i This kind of relationship with a guru—of love, compassion, and intimacy—is one of the cornerstones of the Indian guru tradition. By being with me in all that I am, Sadhguru declares an existential intimacy that attempts to survive our means of communication (email) and the fact that we never really met, at least not online or in a forum of less than hundreds of people. Although the program I participated in was led by Sadhguru himself, it was conducted at a huge convention center in Tampa, Florida, with an audience of around 1500 people — hardly an intimate encounter. Besides this mega-program, I encountered Sadhguru in a talk he gave to few hundred people in his center in Coimbatore, India. In the digital realm however, we met many times and through various platforms.

In order to attend the completion program in Tampa I had to first take Isha’s flagship Inner Engineering program, which is offered online. Moreover, for the last three years I have been watching Sadhguru’s YouTube videos (which I later discovered to be the entry point to his teachings for many of his followers), hosted several of Isha’s apps on my smartphone, followed their Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram accounts, listened to Isha Music on their SoundCloud profile, and received Sadhguru’s daily Mystic Quotes via email. Although my objectives were mainly scholarly, this passive consumption of Isha’s mediated web aligned with existing forms of being part of Sadhguru’s public. At first sight, this mediated guru-disciple relationship does not seem to embody the traditional existential intimacy which supposed to be at its base. However, once we situate this kind of connection in the context of the contemporary media culture in which Sadhguru operates—and which his followers inhabit—a new form of intimacy emerges that is very different from the tradition but not necessarily less intimate or real.

This article explores how digitally networked media allow the formation of intimacy. As this kind of intimacy—which I term Intimacy 2.0—is formed by the digital culture it belongs to, and the ways its public participates in it, I show why scholars of digital religion should examine digital religious practices not only in light of the tradition from which they emerge, but also via the larger technoculture in which these contemporary manifestations are nestled. Following digital media scholar Larissa Hjorth, I use the term technoculture to highlight the importance of our engagement with media over the technologies themselves. Users’ digital engagement, identity, and intimacies should be understood through what they do with these technologies and the role they take in their lives.ii This article takes our digitally networked mode of being in the world as the main element of today’s technoculture, which is also the reason I use the term digitally networked media to describe the websites, social media, and mobile applications I discuss. Digital networks’ modes of production, distribution, and reception shape the ways people are linked to each other, giving rise to what has been called networked publics.iii Unpacking this term, I suggest understanding Sadhguru’s public as a networked devotional public, illuminating digitally networked forms of devotion, bonding, and intimacy. This conceptual framework can be applied to other digital manifestations of devotion, explicating contemporary forms of bonding to and around the sacred.iv

Under the scholarly radar, Sadhguru has emerged as a global leader with millions of followers around the world. Although he is one of many contemporary gurus, Sadhguru stands out due to his exceptional online presence, global appearances, and the different positions of influence he inhabits. Sadhguru and the Isha foundation promote a non-affiliated, non-religious movement with a universal appeal. Promoting technologies for well-being, Isha offers various programs worldwide, including the Inner Engineering previously mentioned, yoga and meditation programs, and rejuvenation facilities, among others. In addition to his spiritual programs, Sadhguru leads various environmental and social initiatives, participates in global leadership forums like the World Economic Forum, speaks at the world’s top business schools, writes regularly for the Huffington Post, has strong ties with the Indian government, and is the author of a New York Times Best Seller. In all his endeavors, Sadhguru exhibits a profound grasp of his public, which is mainly composed of middle class, urban, and professional audience. With the look of an Indian scholar, charisma of a rock star, online output of a millennial media influencer, and a strong sense of his audience, Sadhguru masterfully entwines diverse online and offline networks and successfully migrates the ancient tradition of gurus to the digital realm.

Figure 2: Isha’s Instagram post, promoting their new Alexa skill. Isha Foundation (@isha.foundation), “We are happy to announce the launch of Sadhguru’s official Alexa Skill,” Instagram photo, June 16, 2018.

In accordance with their global reach and universal teachings, Sadhguru and his foundation have a massive online presence. Isha’s mediated web can be difficult to track and accurately depict; it is remarkably rich, constantly updated, and the digital sphere in which it is nestled is infinite. Isha has numerous websites, ranging from sites devoted to the guru or particular programs to online shopping sites, blogs, regional sites for specific countries, and so on. The same goes for smartphone apps; Isha has several apps on both Android and iOS markets, including a general app on Sadhguru, yoga and meditation apps, and Isha chants. These apps provide smartphone users interminable access to the guru’s wisdom and technologies on their own personal devices. Isha even recently released an official Alexa (a virtual assistant developed by Amazon) skill, with which one can use voice command to access Sadhguru’s talks and practices (figure 2).

With over seven million people initiated to his movement worldwide,v it is hard to imagine the ways Sadhguru produces and maintains a relationship with his followers. The intimate nature of the guru–disciple relationship has been described in many different ways, upholding its essential role in the act of learning from a guru. In the Vedic period, the guru and his disciples had to live together to study the Vedas.vi In the Upanishads—literally the act of sitting down near a guru—the relationship was imagined as a “complete harmony.”vii Psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar compares the guru and the disciple to parent and child. Disciples should accept gurus’ teachings with a pure, unquestioning heart. Gurus, respectively, should love their disciples like children. Kakar cites Muktananda, who explains that when you surrender to a guru, “The guru begins to manifest in you; his energy begins to flow into you.”viii Through all its articulations, a sense of an existential intimacy remains, one which affirms, maintains, and relates to one’s existence—through living together, devotion and surrender, or the parental and psychoanalytic functions of the guru. What happens to this existential intimacy when it has to be maintained with millions of followers who are globally spread? How does Sadhguru achieve being with all of them in all that they are?

Contemporary technoculture is characterized by the massive penetration and almost inescapability of digital networks, platforms, and devices. No one can deny that, nowadays, digital media plays an integral role in their users’ lives. Scholars have argued we live in a society in which social and media networks are becoming a single reality through growing integration.ix In this “era of layered presence,”x digitally networked media penetrate all spheres of life, reconfiguring our relation to place, time, culture, other people, and ourselves.xi The most important thing to acknowledge is that media are not mere technologies; media are cultural systems, composed of the technology itself, modes of production and reception, and the larger social practices and relationships in which they operate.xii The technology itself matters, but its larger technoculture—the ways people appropriate it, interact with it, and the meanings and experiences it generates—is what determines media’s imprints on our social lives and webs.

Scholarship defines digital media in many ways, of which I highlight a few. Digital technologies operate on digital code and are construed as interactive, hypertextual multimedia.xiii The hypertextual grammar of the digital world generates an interactive interface, giving users more control over the organization of the narrative. People participate in digital networks by organizing and creating their nodes and paths. This participation is immediate and global; Once we initiated a link by a simple ‘click,’ it immediately took us to the desired node, whether it is by creating that node, such as a Facebook post we write, or by visiting an existing one. This interactivity does not only characterize media consumption but typifies its production. Termed in the mid-2000s, Web 2.0 marks the second stage of the World Wide Web—the stage in which we currently operate.xiv Though a contested term, as there is no clear transition point between stage one and two,xv scholars and industry analysts have come to terms with Web 2.0’s major characteristics. The defining features of Web 2.0 are social-networking sites (popularly called social media) and user-created content.xvi If the first stage of the World Wide Web was more of a passive consumption of information, Web 2.0 is all about interactivity, collaboration, and users’ production of content. Today, in order to be a media producer, one only needs a computer or a smartphone and internet connection. People record their own videos and upload them to YouTube, share the news of current events from their smartphone cameras, and influence public opinion through their Instagram stories. Thus, producers and consumers do not occupy separate roles anymore; they are “participants who interact with each other according to a new set of rules.”xvii

Digital networks push us to rethink concepts like audience, consumers, and users. The participatory nature Web 2.0 generates a more engaged stance, which is foregrounded in the notion of the public. Although Jurgen Habermas and Michael Warner—two of the most influential scholars of publics—present different understandings of the idea of a (or the) public, I identify traces of both approaches in today’s digitally networked publics. Habermas identifies the rise of the public sphere in early eighteenth-century bourgeois spaces in which rational and critical debate had developed. These discursive sites became the public sphere—a cornerstone in constructing modern democracy. Warner is more interested in a heterogeneous and dynamic notion of publics. For him, a public “comes into being only in relation to texts and their circulation.”xviii If Habermas’ public—as a discursive site—is constituted through engaged participation, Warner’s public—as a social imaginary—unites strangers through attention to a specific discourse.xix Networked publics are created both through engagement and participation in the production of a mediated discourse, as well as through reception of these discourses. The global, accessible, and open end-to-end and many-to-many characteristics of digital networks allow people to engage “in shared culture and knowledge through discourse and social exchange, as well as through acts of media reception.”xx This engaged and pervasive use of digital platforms and devices weaves its publics into a global network like no previous medium has managed to do.xxi There is no more unilateral distribution of content, allowing digital networks to be catalyzers or facilitators of contemporary social movements and upheavals.xxii Mobile phones exemplify the accessibility of networking infrastructure. “[U]sers rely on handheld devices to maintain an always-on relation to information and personal networks, as well as utilizing them as ready-at-hand digital production devices for snapping photos and crafting text messages.”xxiii Digital networks allow individuals to connect with those they are close to, or with complete strangers, from wherever they are.

Following the idea of a networked public, I suggest understanding Sadhguru’s public as a networked devotional public. I argue that this public is not only assembled by virtue of the web, but also has a major role in producing it. Nonetheless, this public includes various degrees of participation, for which the experience of Sadhguru differs. For a major part of Isha’s networked public, participation comes in the form of attention to the foundation’s discourse, echoing Warner’s idea of a public.xxiv Some also participate in its programs and digitally mediated practices. For a lot of them, it ends there; However, many others embody a more Habermasian sense of the public, becoming part of the organization by volunteering. Isha declares to be an almost entirely volunteer-run organization;xxv In fact, Isha’s networked publics are responsible for the production of the foundation’s discourse and Sadhguru’s image online and offline. As they bring skills from other networks and cultures into this production—termed by Isha as skill-based volunteeringxxvi—they facilitate Sadhguru’s mastery of the various cultures and networks he navigates. This segment of the Isha public is clearly devotional, as they break through a digitally mediated relationship, finding their way to surrender to it. Nonetheless, I argue that also the rest of Isha’s public maintains a sense of relationship with the guru, albeit through digitally mediated networks.

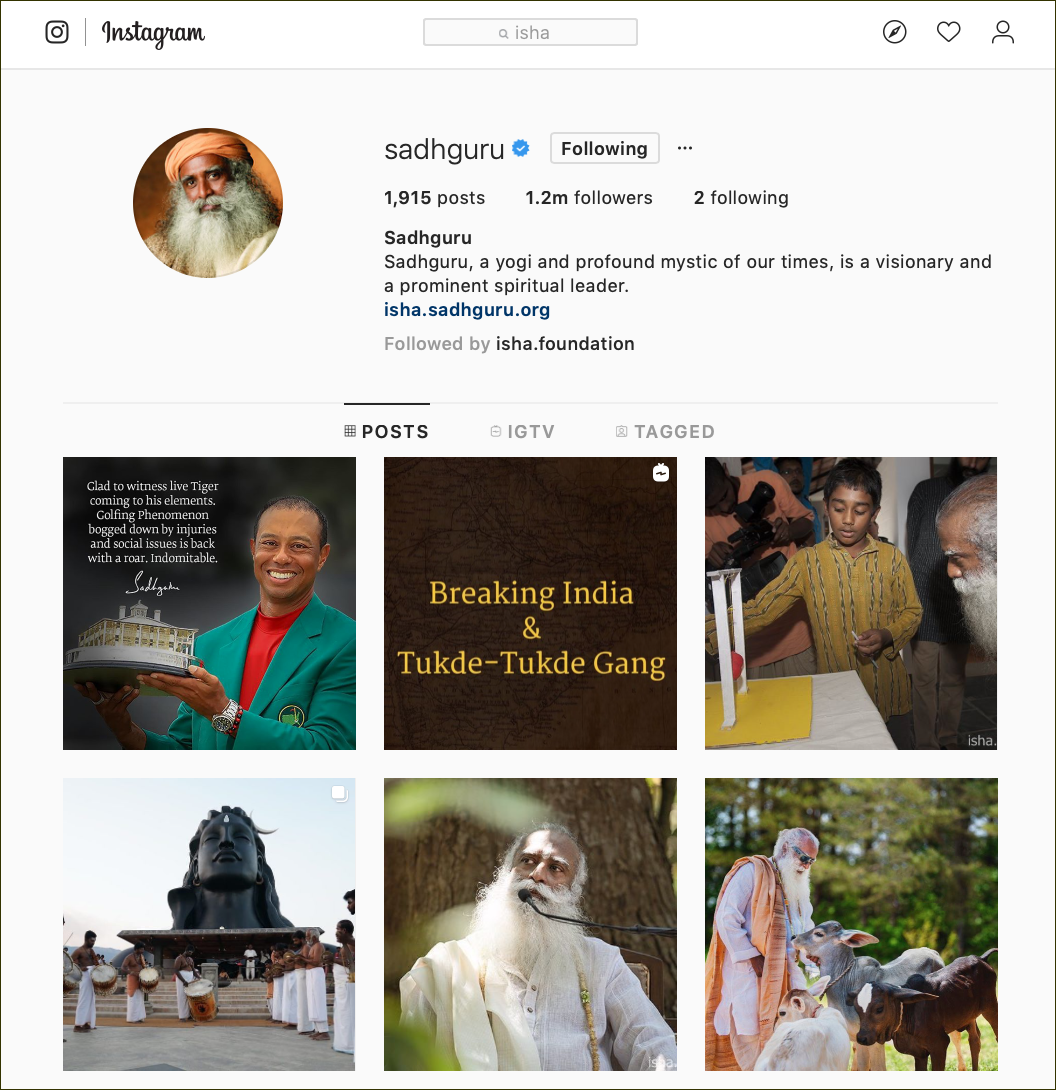

Isha’s Instagram page. Screen capture. April 2019.

Long ago, Marshall McLuhan argued that media function as prostheses.xxvii This statement could not be truer today, when we are constantly in arm’s reach of our smartphones—or even wear smartwatches around our wrist—creating an intimate bodily connection with the digital. But this intimate connection goes way beyond the corporeal; it is our engagement with digital platforms and devices that matters for the creation of close relationships with and through digitally networked media. Hjorth explains that, in the participatory culture of Web 2.0, social media is a common and prevalent method for self-representation. Web 2.0’s technoculture strengthen the now prevalent view that these virtual settings are in no way less real, but are part of users’ everyday existence, and that offline and online spaces are simply different aspects of it. Digital networks are even perceived by scholarship to be our immediate surroundings; their encompassing nature shapes the way we know and interact with our social circles, as we share and conduct our most intimate relationships and moments over social media. Using social media, users develop a feeling of knowing others through ‘ambient awareness.’ These ways of knowing are ambient as they are produced by the “background presence of ubiquitous media environments”xxviii and our peripheral awareness of them. This awareness also results in a unique kind of co-presence. Though all communication technologies strive to create a sense of co-presence from a distance—like letters and telephones—contemporary digitally networked media create an ‘ambient co-presence’ as “the peripheral, yet intense awareness of distant others made possible through the affordances of ubiquitous media environments.”xxix Media sociologist Ichiyo Habuchi expands this co-presence with the idea of the telecocoon as a “zone of intimacy in which people can continuously maintain their relationships with others who they have already encountered without being restricted by geography and time.”xxx

By the term Intimacy 2.0xxxi, I attempt to describe the ways Web 2.0 and its ambient qualities bring new ways of forming intimate relationships, illuminating the spiritual and existential intimacy of the guru–disciple relationship as produced by Sadhguru’s mediated networks. I do not attempt to portray a different kind of intimacy but new methods of its production and maintenance, which are determined by contemporary circumstances. Media scholar Shaka McGlotten refers to screen-mediated intimacies as “virtual intimacies,” but their virtual aspect does not make them less real.xxxii Instead of looking at these intimacies as of lower quality, they allow us to question the nature of intimacy itself. Although there is not one definition of the term, intimacy is commonly understood to be founded on self-disclosure and “familiarity resulting from close association.”xxxiii As social media profiles revolve around self-disclosure of both public and personal aspects of life, its encompassing nature can lead to a feeling of closeness that is referred to as “ambient intimacy.” This kind of intimacy can occur in mediated relationships with a stranger or a celebrity, but it can also assist in maintaining existing relationships,xxxiv like in the case of the telecocoon. Although based on the notion of “ambient intimacy,” intimacy 2.0 is slightly different as it takes into account the interactive and participatory elements of the medium and its culture—in other words, as it is based on networked publics’ engagement, expression, and identity formed through Web 2.0. The feeling of ambient co-presence can lead to that sense of closeness that is seen as the basis of intimacy. Nonetheless, in the guru–disciple relationship, the intimacy is not necessarily based on co-presence or on self-disclosure, at least not in the informative way. By entering into a relationship with a guru, the disciple does not necessarily disclose much about herself, but she does agree to surrender the self.

It might be easier to detect this kind of surrender in Isha’s volunteering structure. However, by showing the digital ways in which Isha generates ambient co-presence and awareness of Sadhguru—producing the intimate sphere of the telecocoon—I argue that Isha manages to establish a sense of closeness and intimacy with the guru even in the segments of its public that mostly participate through attention. The guru’s videos in social media and in Isha’s programs assume a special role in this attempt, producing the sense of a one-on-one relationship with the guru. Religious studies scholar Joanne Waghorne refers to the videos and web streams used by Isha as creating “a mediated sense of intimacy between the guru and the students that defies space and even time.”xxxv Most people I talked to at the completion program came there after stumbling upon Sadhguru’s videos on YouTube. Moreover, few of them said that although being in the presence of the guru in Tampa, they felt that hosting the guru in their private space—while taking the online program through their personal devices—was more effective in producing an intimate relationship with him. An Isha volunteer, with whom I had several friendly conversations, reiterates this through her own experience.

“For me starting out, the videos were foundational to establish that relationship with him [Sadhguru] and feel comfortable with who he is and to develop that trust in someone, to figure out who someone is . . . I think that without the videos I may have never even been willing to try it, unless I met him in person. xxxvi”

This volunteer points to the crucial role of the videos in her involvement with Isha and the ways they replaced an in-person encounter, binding her to the guru. Now, she does not need the videos to feel this sense of intimacy. She feels it when she is doing her practices or volunteers for Isha — her form of surrender. Nevertheless, she still watches a video of Sadhguru at least once a day. Both in the online program and on YouTube, Sadhguru’s videos cultivate a personal bond with the guru through simulating a one-on-one encounter. Imitating the traditional guru setting, the videos allow for an intimate relationship to emerge, afterward maintained by an ambient co-presence of the guru.

Figure 3: Wake Up to Wisdom: Mystic Quote. Sadhguru, December 9, 2018.

The guru’s massive digital presence in his public’s lives positions him in a new mode of intimacy with his followers. From guided meditation and yoga to videos of the guru, Sadhguru’s teachings are easily accessible to his networked public, on their most intimate and personal devices. Isha’s mailing lists serve as a good example. Once registered at one of Isha’s websites or to a specific program, followers start receiving daily mails with quotes of the guru, called “Wake up to Wisdom: Mystic Quote.” These emails are sent every day at the same time and always include a Sadhguru quote and image (figure 3). In lieu of the traditional cohabitation with the guru, Isha meditators wake up to his image and teachings in their digital habitat—their personal inbox—fostering a digital co-presence with him.

In conclusion, as social anthropologists Jacob Copeman and Aya Ikegame suggest, “Cautious manipulation of media forms makes it possible to have an intimate one-on-one relationship with a guru who might otherwise seem distant and inaccessible.”xxxvii Making himself available to his followers, Sadhguru masters the various social media platforms. Whether it is Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, SoundCloud, Pinterest, or YouTube, Sadhguru and Isha are there and posting, always utilizing the most current features of the networks. In this way, Isha generates the same ambient awareness and co-presence its followers are familiar with from their other social relationships, as well as extending the understanding of self-surrender to the guru. Members can be in constant connection with the guru, his activities, teachings, and whereabouts as part of the background presence of these media environments in their lives. Members can choose the preferred social network on which to be in constant touch with the guru.xxxviii They do not necessarily need to actively look for it, since it is already there in their peripheral awareness. Although this utilization of social media does not exactly count for self-disclosure, it is possible to say that Sadhguru puts himself and his ideas out there for his followers to devour as part of their online existence. Sadhguru’s digital availability allow him to become part of his disciples’ existence, which is constantly surrounded by digitally networked media, in the new intimate space of the telecocoon. Producing an intimate and emotional connection with a global following via digitally networked media, Sadhguru gathers around him a networked devotional public, linked to him and to each other while remaining in their respective locales.

Endnotes

i Isha USA, “Blessings from Sadhguru.” Italics added.

ii Larissa Hjorth, “Web U2: Emerging Online Communities and Gendered Intimacy in the Asia-Pacific Region,” Knowledge, Technology & Policy 22, no. 2 (2009): 118.

iii This term, which I elaborate on shortly, is borrowed from the eye-opening work of the Networked Publics Research Group, the Annenberg Center for Communication at the University of Southern Florida, as published in Kazys Varnelis, ed., Networked Publics (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008).

iv Although Sadhguru does not conceive himself as a divine figure—nor his movement as a religion—I contend that his followers do exhibit devotion, especially as Sadhguru and his teachings emerge from a long and established tradition of devotional guru-disciple relationship.

v “Volunteer at Isha,” Isha Foundation, accessed March 28, 2019.

Here it is mentioned that Isha is supported by seven million volunteers. In order to volunteer one has to be initiated to the movement, meaning that at least this amount of people had been initiated to the movement.

vi M. K. Raina, “Guru-Shishya Relationship in Indian Culture: The Possibility of a Creative Resilient Framework,” Psychology and Developing Societies 14, no. 1 (2002): 173.

vii Raina, “Guru-Shishya Relationship in Indian Culture,” 181-182.

viii Sudhir Kakar, “The Irresistible Charm of Godmen,” India Today, April 29, 2011,

ix Van Dijk, The Network Society; Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, 2nd ed. (New York: Wiley Blackwell, 2011).

x Mizuko Ito, “Introduction,” in Networked Publics, ed. Kazys Varnelis (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008), 6.

xi Not for nothing, claims have also been made against this always-on, constantly networked mode of being in the world and its possible side effects. For an example see Franco Berardi’s idea of the anthropological cognitive mutation produced by the acceleration of the Infosphere. Franco Berardi, “The Paradox of Media Activism: The Net is Not a Tool, It’s an Environment,” Ibraaz-Contemporary Visual Culture in North Africa and the Middle East, November 2, 2012.

xii For a discussion on the different aspects of media see Mark B. N. Hansen and W. J. T. Mitchell, “Introduction,” in Critical Terms for Media Studies, eds. Mark B. N. Hansen and W. J. T. Mitchell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), vii-xxii.

xiii José Luis Orihuela, “eCommunication: The 10 Paradigms of Media in the Digital Age,” in Towards New Media Paradigms: Content, Producers, Organisations and Audiences, eds. Ramon Salaverría and Charo Sádaba (Pamplona: Ediciones Eunate, 2004), 129-35; Van Dijk, The Network Society, 9.

xiv Internet analysts and scholars attest that we are on the verge of the third stage, web 3.0, but it is yet to come.

xv Mary Madden and Susannah Fox, “Riding the Waves of ‘Web 2.0’,” Pew Internet & American Life Project (2006): 1-6.

xvi Hjorth, “Web U2,” 117-18.

xvii I Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 3.

xviii Michael Warner, “Publics and Counterpublics,” Public culture 14, no. 1 (2002): 50.

xix For an elaborate discussion on the idea of publics according to these thinkers see Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry Into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans.Thomas Burger with the assistance of Frederick Lawrence (Cambridge: The MIT press, 1991); Warner, “Publics and Counterpublics.”

xx Ito, “Introduction,” 3.

xxi Although Marshal McLuhan already talked on the global village in 1964, I do not think he could have anticipated the levels and scope this phenomenon will reach.

xxii Negar Mottahedeh, #iranelection: Hashtag Solidarity and the Transformation of Online Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015).

xxiii Ito, “Introduction,” 6.

xxiv Michael Warner, “Publics and Counterpublics,” 60-2.

xxv Isha Foundation, “Volunteer at Isha.”

xxvi “Skill Based Volunteering,” Isha Foundation, accessed September 30, 2018

xxvii Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

xxviii Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

[1] Mirca Madianou, “Ambient Co-Presence: Transnational Family Practices in Polymedia Environments.” Global Networks 16, no. 2 (2016): 183.

xxix Madianou, “Ambient Co-Presence.”

xxx Ichiyo Habuchi, “Accelerating Reflexivity,” in Personal, Portable, Pedestrian: Mobile Phones in Japanese life, eds. Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe, and Misa Matsud (Cambridge: MIT press, 2005), 167.

xxxi Computer scientist Kieron O’Hara uses this term slightly different, referring to the loss of privacy that comes with contemporary social media use culture. Kieron O’Hara, “Intimacy 2.0: Privacy Rights and Privacy Responsibilities on the World Wide Web,” Web Science Conference 2010.

xxxii Shaka McGlotten, “Virtual Intimacies: Love, Addiction, and Identity @The Matrix,” in Queer Online: Media Technology & Sexuality, eds. Kate O’Riordan and David J. Phillips (New York: Peter Lang, 2007), 125-26.

xxxiii Lynn Jamieson, “Intimacy,” In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, G. Ritzer, ed., 2007. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosi071.

xxxiv Ruoyun Lin, Ana Levordashka, and Sonja Utz, “Ambient Intimacy on Twitter,” Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 10, no. 1 (2016). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2016-1-6.

xxxv Joanne Punzo Waghorne, “Engineering an Artful Practice: On Jaggi Vasudev’s Isha Yoga and Sri Sri Ravishankar’s Art of Living,” in Gurus of Modern Yoga, eds. Mark Singleton and Ellen Goldberg (New York: Oxford University Press: 2013), 294.

xxxvi Isha volunteer, conversation with author, October 22, 2017.

xxxvii Jacob Copeman and Aya Ikegame, “Guru logics,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2, no. 1 (2012): 311.

xxxviii As each follower regularly uses different platforms, the number of followers Sadhguru and Isha have in each platform varies. For illustration, on October 1, 2018 Sadhguru had 4 million followers on Facebook, almost 2 million on Twitter, and a bit more than half a million on Instagram.