Cecil John Rhodes: ‘The Complete Gentleman’ of Imperial Dominance

Abstract

This paper demonstrates how incompleteness engenders an understanding of resilient colonialism epitomised by Cecil Rhodes’ monuments and statues in Southern Africa. The paper makes a case for the building of inclusive, representative, accommodating and accommodated monuments and statues. It draws on Tutuola’s metaphorical ‘The Complete Gentleman’ and the lessons on being and becoming from Tutuola’s skull thereof to remind us that Rhodes’ legacy just like his life still suffers from illusions of completeness and a denial of debt and indebtedness. It concludes that the call for humility and alertness to the sensitivities and sensibilities of the various shades of the imagined dream of a rainbow nation demands that South Africans stop learning the wrong lessons from Rhodes, namely: exclusionary articulations of being, becoming and belonging informed by unequal encounters fuelled by ambitions of superiority and zero-sum games of conquest. The paper challenges the reader to reflect on how stifling frameworks of citizenship and belonging predicated upon hierarchies of humanity and mobility and driven by a burning but elusive quest for completeness can be productively transcended by humility and conviviality inspired by taking incompleteness seriously and positively.

Citation: Nyamnjoh, Francis B. “Cecil John Rhodes: ‘The Complete Gentleman’ of Imperial Dominance.” The Jugaad Project, 23 Feb. 2021, thejugaadproject.pub/rhodes-the-complete-gentleman [date of access]

Photo of author on the left, visiting the Rhodes Memorial, with friends from the USA. Cape Town, 2020. Image by author

Introduction

In South Africa – just like in the UK and much of Europe – there is an ongoing debate on what to do with statues and monuments erected in honour of colonialism and imperialism, the particularly controversial ones especially. This resembles the Black Lives Matter movement in the USA where the statues and monuments in question are linked to the enslavement of African-Americans and the civil war of the confederacy era. Like elsewhere, opinion is divided in South Africa. Some have suggested that they be collected and placed in a public park, in museums, or even at Robben Island. Others want them left where they are currently located, as historical records, stressing the need to have statues and monuments in places where they are visible enough to be critically interrogated on a regular basis. Still others suggest a concerted process of recalibration in the interest of nation-building. This group appeal to accommodation and inclusiveness as a clarion call of sanity with great promise for the future of South Africa. However, for existing colonial statues and monuments to signify anything but oppression, dispossession and painful memories of excruciating torture and dehumanisation of Africans and Asians imported as indentured labour, they would have to be re-articulated, recalibrated and reconfigured into multicultural symbols of reconciliation and a compositeness of being. This calls for humility and alertness to the sensitivities and sensibilities of the various shades of the imagined dream of the rainbow nation that South Africa aspires to be. This paper explores the advantages of approaching the question of statues and monuments with a more accommodating logic informed by incompleteness, recognising debt and indebtedness in the making, unmaking and remaking of history, its achievements, consecrations and choices of what qualifies to be celebrated in a truly inclusive and open-ended manner.

The paper invites the reader to use the reality and idea of incompleteness as a template and prism through which to understand the problem with contested monuments and statues such as those erected in honour of Cecil John Rhodes the prominent anchor and driver of British colonialism and imperialism in Southern Africa. The intent is also to inspire solutions on how we could build monuments and statues that could be more inclusive, representative, accommodating and accommodated. The paper argues that incompleteness is normal and universal, not as a negative attribute of being, but as something to embrace and celebrate, as we, in all humility seek to act and interact with one another, with the things we create to extend ourselves, and with the natural and supernatural worlds relevant to our sense of being and becoming. To recognise and provide for incompleteness is not to plead guilty, inadequate and helplessness vis-à-vis the supposedly complete others. Instead, incompleteness is a disposition that enables us to act in particular ways to achieve our ends in a world or universe of myriad interconnections of sentient incomplete beings and actors, human and non-human, natural and supernatural, amenable and not amenable to perception through our senses.

In a universe of incompleteness, the quest to activate oneself for potency required to fulfil a desire or a need entails motion that brings one into contact and interaction with equally incomplete mobile others. Some move around with the idea of getting by in mutual respect with others that they encounter. They reach out to the others and draw on them in their incompleteness what attributes they need to enhance themselves. Mobility is a constant and universal. Everything and everyone moves, and life would not be possible without mobility. We would be incapable of doing much about our incompleteness if we could not move and encounter other equally incomplete others to interact and mutually activate ourselves.

Throughout history, people have used both their incompleteness and their mobility in different ways. Some think that incompleteness is a negative, something to transcend towards a linear progression to something you might call completeness. They believe that completeness is possible, that it comes from using your mobility, reaching out and encountering others in unequal ways, conquering them and imposing one’s superiority. However, not every mobility has to be animated by such ambitions of conquest, domination or suppression. Others move around, informed by the understanding that if incompleteness is the norm, it is an illusion, and a perilous one at that, to pursue completeness, especially if completeness is defined in zero sum terms as independence or autonomy. Suppose one does not recognise that incompleteness will always be with one even in one’s supposed superiority and autonomy. In that case, one could easily develop the arrogance of not recognising one’s debt and the fact of one’s indebtedness to others.

When one provides for incompleteness as a permanent feature and disabuses oneself of ambitions of dominance, one develops a disposition that privileges interconnections, interdependences and the reality of debt and indebtedness. An awareness that a life of incompleteness is ultimately about recognising and providing for debt and indebtedness, of which no one is free. Put differently, we are who we are through a process of interdependence and indebtedness. This recognition facilitates the cultivation of a disposition of humility that enables one to see and provide for interconnections. One is who one is because of others. Even if one does not always service one’s debts, let alone repay them, one is conscious that one is not self-made. At the same time, one is the product of various networks of interconnections, to the production and reproduction of which one actively contributes. The current debate about colonial monuments and statues in South Africa and elsewhere, I posit, could be enriched by the notions of incompleteness and conviviality. I develop this further below.

Amos Tutuola’s Metaphorical ‘The Complete Gentleman’

The late Nigerian writer, Amos Tutuola – author of The Palm-Wine Drinkard, and My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, published respectively in 1952 and 1954 in London by Faber and Faber – was a genius at depicting the universes of incompleteness popular across West and Central Africa. One example from The Palm-Wine Drinkard illustrates the point of this paper superbly. The story revolves around a very dependent, overly materially endowed drunk, who believes that he is independent because of the predictable regularity of service and servitude he receives from his faithful, virtually enslaved, harvester of palm wine. Instead of celebrating the fact of belonging with and because of others, the Drinkard dramatizes his illusions of probed up independence, power and privilege. Then, suddenly, he is made aware of just how dependent he really is, when the palm wine harvester and provider falls from a tall palm tree and dies. During his quest for his palm wine provider who has suddenly dropped dead – a quest best understood as a masterclass of a guided tour on the infinite possibilities of incompleteness by Tutuola –, the Drinkard comes to a town where a beautiful girl has been lured away by the ‘Complete Gentleman’ into the distant bushes inhabited by curious creatures.

It happens that the ‘Complete Gentleman’ is not that complete. There is a lot less to his glitter and sparkle than meets the eye. His charm and handsomeness are less than skin deep. Indeed, almost everything about him belongs to others. He is in every way a composite being – a sort of ubuntu human. He belongs with a community of curious creatures who are reduced to a bare-bones lifestyle, deep in the bushes – they live their lives as skulls. When the wind blows their way rumours of a beautiful young girl in a distant town who repeatedly turns down every suitor, this curious creature reasons that a girl who turns down every man’s hand in marriage must want as husband an otherworldly man. So, he decides to try his luck by embarking on a self-enhancement journey by borrowing body parts from others along the way to the town of the girl with high standards. He borrows all the body parts he needs, as well as a lovely outfit and a horse. As a composite being, he feels genuinely handsome. In Tutuola’s words, the skull turns human thanks to his borrowing, and ultimately becomes ‘The Complete Gentleman’.

As soon as the girl sets eyes on him, she abandons everything and everyone and decides to follow him. Unlike the Drinkard who is oblivious of what makes him who he is, The skull activated into a gentleman is as gentlemanly as he appears to be complete. He warns the girl repeatedly that there is a lot less to him than meets the eye. But the girl insists that she has found what she desires: a truly handsome gentleman – the realisation of her fantasy. Her eyes know what they have seen, and she trusts her feelings. At the crossroads, he warns her for the last time, but when she insists, he branches off and takes the path leading back to his community of skulls deep in the bushes. As junctions of myriad encounters, crossroads in Tutuola’s universe are significant in the way they facilitate creative conversations and challenge regressive logics of exclusionary claims and articulations of identities and achievements. Having acquired the wife he had set out to win, and being the gentleman that he indeed is, the man begins the process of self-deactivation or self-decomposition by returning all the things (material cultural indicators of privilege, wealth and handsomeness) and body parts that he had borrowed for the occasion and paying the agreed price to the lenders. The bride learns too late how deceptive appearances sometimes are. If only ‘The Complete Gentleman’ were not so much of a gentleman as to insist on recognising and paying back the debt of things and body parts he owed others, if only he was more selfish and self-centred as to unfairly dispossess others permanently, he just might have continued to live a lie.

Lessons on Being and Becoming from Tutuola’s Skull

The story of the skull that can activate itself into a complete gentleman to achieve an end, and then reverse itself to being just a skull once again, provides us with a prism through which to make sense of being and becoming, as a permanent work in progress. The story suggests that everything in the world and in life is incomplete: nature is incomplete, the supernatural is incomplete, humans are incomplete, and so are human action and human achievement. Such incompleteness implies that people are not singular and unified in their form and content, even as their appearance might suggest that they are. And so are other creatures and things. Fluidity, compositeness of being and the capacity to be omnipresent in whole or in fragments are core characteristics of the reality and ontology of incompleteness, and the ethic of conviviality and ubuntu that they entail.

It is in recognition of incompleteness that human beings are ever so eager to seek ways of enhancing themselves through relationships with other human beings. In using their creativity and imagination to forge solidarities, they acquire magical objects or technologies that can help improve their relationships with fellow humans. Such objects and technologies also come in handy in dealing with the whims and caprices of natural and supernatural forces and agents.

Being incomplete necessitates and explains mobility and action to pursue activation for individual and collective self-fulfilment. Being and becoming are possible only through endless and flexible mobility in quests for activation, potency and efficacy. Even the predictably constituted can move and reconstitute themselves in familiar and unfamiliar ways. Nothing is ever entirely what it seems. There is always a lot more or a lot less to things than meets the eye.

It is thus essential to factor into our perception and analysis the reality of social action informed by the constancy of mobility occasioned by the permanence of incompleteness. Whatever the claims made to the contrary, our perception and analysis of reality are impoverished whenever we lose sight that everything moves – people, things and ideas – in predictable and unpredictable ways. The circulation of things, ideas and people is not the monopoly of any particular group, community or society. Mobility and circulation lead to encounters of various forms, encounters that are (re)defining in myriad ways. If people, their possessions and ideas circulate, it follows that their identities, personal or collective, move as well. And through encounters with others, mobile people constantly have to navigate, negotiate, accommodate or reject difference (in things, ideas, practices and relations) in a manner that makes of them a permanent work in progress. No mobility or interaction with others leaves anyone, anything or any idea indifferent, even if such interactions are not always equal and do not always result in immediate, palpable or tangible change. No encounter in mobility results in uncontested domination or total passivity. Even as some may wilt in the face of domination, some resist it fervently. Others can navigate and negotiate the tensions and contradictions brought about by the reality of domination in complex, creative and innovative ways. Sometimes this holds the potential for new and more convivial forms of identity.

Mobility is a permanence because incompleteness is an enduring condition. The quest for extensions to repair one’s state of incompleteness only makes one realise one’s incompleteness when confronted with all manner of extensions that one has not mastered. Moreover, extensions tend to work only partly, and only some of the time—and some of them do undermine the degree of completion one thought one had achieved. The fact that the pursuit of completeness is elusive and illusory, (and can only unleash sterile ambitions of conquest and zero-sum games of superiority), is an invitation to explore, contemplate and provide for a world of infinite interconnections, fluidities and conviviality. It is an invitation to a world in which no one has the monopoly of power or powerlessness, in which humans and things complement each other and double as one another. Power is fluid, and so is weakness. We are self-consciously incomplete beings, constantly in need of activation, potency, and enhancement through conviviality and ubuntu relationships with incomplete others.

In light of the ubiquity of incompleteness, Ubuntu as a social organising principle encourages a life of mutuality, obligation and reciprocity. Ubuntu emphasises a continuous act of sharing (giving) to maintain a balance of reciprocity between oneself and others. Only through continuous circulation of relationships and things can one guarantee activation, potency and efficacy for competing and complementary incompleteness that account for our flexible compositeness of being. Ubuntu and conviviality insist on interconnections and interdependencies. They suggest a perception and an approach to life, sociality, encounters and relationships mindful of the importance and centrality of charging, discharging and recharging. One can only stay permanently charged if one is in splendid isolation, disconnected, aloof and inactive. Even then, one’s charge risks leaking or wasting away (draining itself out unproductively for lack of interactivity). With that, one’s life eventually also drains away with little to bequeath to society and the world, which has given so generously to one. To be social and in relationship and interaction with others requires and simultaneously makes possible actively charging, discharging and recharging oneself and the others involved. Discharging within relationships is not a wasteful exercise as it entails charging others (energy expended is not necessarily energy depleted). Just as recharging entails drawing from the charge of (or being energized by) others. Symbiotic relationships and sociality are full of charge, discharge and recharge. When one loses one’s charge to others in a social relationship, that cannot be considered as sterile leakage or wastefulness, as long as recharge or reactivation is possible. Ultimately, being human is all about debt and indebtedness. It is about the need to recognise and provide that life is all about the circulation of debt. It is crucial to recognise the reality of one’s eternal indebtedness to others – be these fellow human beings, the natural environment and its resources, or the supernatural forces and one’s ancestors.

Rhodes and the Illusions of Completeness

Cecil John Rhodes, who lived from 1853 to 1902, was no different from Tutuola’s skull before, during and at the end of his African treasure-hunting adventure of self enhancement through the things and bodies of others. There is little in his life that speaks to the image of the self-made man that we have grown used to from reading of him in history books. Many carefully choreographed public relations publications have served to prop him up as a larger-than-life messiah of the British Empire. According to Brown, many of Rhodes’ myths, including ‘the myth of Rhodes the Colossus, the Founder, the Immense and Brooding Spirit’, were created after his death (2015: 236).

De-headed statue of Rhodes at the memorial. Cape Town, 2020. Photo by author.

Rhodes Grave at the Matopos Hills. Photo by Janet Mate.

Put differently, and although after he died in 1902, Rhodes was reduced to a mere skull in a grave at the Matopos Hills of Matabeleland in Zimbabwe, it has continued to be activated and reactivated to achieve the ends of the fading empire he left behind. And especially to continue with his conquest and dominance ambitions, following his last words, ‘So little done, so much to do’ (Brown 2015: 22; see also Baker 1934: 123-125). The empire needed a complete gentleman’s permanent status to embody its ideals of racial superiority and dreams of conquest. Rhodes’s journeys, encounters and life, coincided with such imperial aspirations, which he assumed and has continued to serve even when reduced to a skull. Thanks to such coincidence of ambition and trajectory, Rhodes became ‘the embodiment of the imperial ideal; a personification of all the glories of the British Empire’ (Roberts 1987: 2-3). ‘As his fortune and political influence grew, as the arid earth and the high savannah produced a cornucopia of diamonds and gold beyond imagining, Rhodes began to feel he had been put on this earth for some greater purpose. He would expand the English-speaking sphere of influence until it was so powerful that no nation would dare oppose it, and war would be a thing of the past…’ (Brown 2015: 18).

Beyond the myths of a superman, genius, visionary and absolute completeness, the story of Rhodes’ life, just like the story of Tutuola’s skull, is that of a man who struggled with different dimensions of incompleteness. A man who was born incomplete, he lived seeking after the elusive completeness, and died an incomplete man. It was up to those who shared his ambitions of dominance, to continue the task of corrupting, and deliberately ignoring the facts of his life, to perpetuate the illusions of him as a self-made man, ‘The Complete Gentleman’. My book, #RhodesMustFall: Nibbling at Resilient Colonialism in South Africa (2016), is replete with accounts of Rhodes’ ordinariness of being, and catalogues his incompleteness, which should not have generated the depictions of him as the larger-than-life figure if those doing the representations cared about the facts of his existence. ‘Because Rhodes the individual human being is as scarce as a rare diamond (e.g. “the South African Star”), Rhodes the stereotype, the caricature and the figment of the imagination lends himself easily to prototyping and rationalising, and as an excuse or a scapegoat’ (Nyamnjoh 2016: 38).

Rhodes did not arrive with power and privilege in his briefcase in his tropical treasure-hunter adventures, but acquired both through his interactions with others in what today constitutes Southern Africa, which proved to be a happy hunting ground for him and other Europeans. Like Tutuola’s skull and every other nimble-footed stranger, or anyone, who, conscious of their incompleteness, seeks encounters with the hope of activating their potential to fulfil themselves, Rhodes needed the opportunities of the land of his adventures, to activate whatever capacity for fortune, power and privilege. Compared to some present-day nimble-footed Africans whose mobility is heavily policed but who refuse to yield to victimhood, Rhodes arrived with fewer credentials in his briefcase, except for ‘£2000 of capital loaned to him by Aunt Sophia and an allowance from his father with which to work his colonist’s grant of fifty acres and the additional land he intended to buy’ (Flint 1974: 13). He arrived without a university degree – something many a present day nimble-footed African flowing into South Africa possess – , and as a sickly seventeen-year-old whom few believed would live long enough to threaten or be threatened by those he encountered (Roberts 1987: 1-14). As John Flint puts it, ‘physically weak and prone to sickness’, Rhodes was a most ‘unlikely vehicle for greatness’. Indeed, Rhodes may have been ‘shrewd’ and ‘calculating’, but he was far from ‘highly intelligent’ and ‘his mind lacked power, thrust and originality’. If anything, he ‘remained locked in the fantasies of a schoolboy’, often ‘suspicious, lonely, [and] isolated’ (Flint 1974: xiv-xv). (p.8-9).

However, when history and science are co-opted by ideologies of dominance as is the case with every unequal encounter, the truth is hardly allowed to stand in the way of a good story. The good story is what Britain and Europe have wanted to tell themselves through insistence on justifying as genius, visionary and benevolence the racialised aggression and indignities that they inflicted upon others in the course of dispossessing them of their land, humanity and capacity to self-determine. They have preferred and perpetuated such an empirically baseless tale instead of calling their excesses and impunities out for what they were: the pursuit of illusions of completeness through unfounded theories of superiority, by borrowing without acknowledging, and systematically turning a blind eye on their debt and indebtedness to other peoples, other geographies, other ideas of being, personhood, agency, creativity, innovation and the symbolisation of achievements. Put differently, the myth of Rhodes as the self-made man would not be sustainable, without the myth of racial supremacy serving to justify his aggressive pursuit of material wealth and national glory with ruthless and reckless abandon. All of these, with callous disregard for the humanity of perceived lesser others (Plomer 1984 [1933]: 72).

Many spaces and places have been named after Rhodes in South Africa, honouring his public image and status as ‘The Complete Gentleman’ of imperial dominance. As a crowning glory of his achievements, and in recognition of his generous donation of some of ‘his’ land – the Groote Schuur Estate19 – and ‘his’ wealth to the University of Cape Town (UCT) (Phillips 1993: 2, 136, 145-148, 220-221; Baker 1934: 37-55), where several places, spaces, buildings and things are named after him and his fellow European disciples (old and new, dead and alive), a most provocatively imposing blot-on-the-landscape statue was erected in Rhodes’s honour at the very heart of the campus. Before its removal following student protests in 2015, there sat his bronzed likeness, overlooking the city and seemingly yearning for the lands beyond.

Statue being taken down. Cape Town, 2015. Photo by Wandile Goozen Kasibe.

Njabulo Ndebele, former VC of UCT, describes Rhodes’s ubiquitous godlike presence, symbolised by the statue sculpted by Marion Walgate and unveiled in 1934, as evoking strong emotions:

He is either praised or denounced, admired or mocked. Enduring controversy around him has assured him an indelible place in history. Whichever way you turn, you will encounter him, whether on campus, or elsewhere in South Africa; or beyond, in Zimbabwe. His name, Cecil John Rhodes, echoes from Cape to Cairo, the span of continental distance by which he expressed the extent of his vision.

You may not see him clearly in the iconic wide-angle view of UCT. Yet he is decidedly there. Perhaps it is just as well that his visual presence is not more prominent. He is part of campus history, not the whole of it.

Rhodes is memorialised on campus by a bronze statue of him, now weathered green by time. On a closer look you will make him out, the hippo on the surface of UCT’s river of time, defying casual embarrassment and willed inclinations to have it submerge, perhaps forever. Its broad back defiantly in view, it is never to be recalled without thoughts and feelings that take away peace of mind.

Indeed, Rhodes, the donor of the land on which the University of Cape Town was built, exerts a presence on campus which often prompts a desire for his absence. But, like Moby Dick the whale, he will blow.[1]

For a snippet of why many find it hard to reconcile with, let alone praise or admire Rhodes, here is a window into how he activated himself by wasting away the lives and humanity of the people he encountered in the course of his Southern African adventures. Rhodes used ‘a harsh racially-determined labour system’ to create ‘a supply of landless labourers’ (Hyam 1976: 298). ‘Desperate for labor as the mines grew deeper, he used blacks ruthlessly, penning them up in compounds, destroying their family and tribal life, and giving them wages that made them little better than slaves, so creating the economic base of apartheid’ (Flint 1974: xv).

Rhodes Deactivated by Debt and Indebtedness

What happens when we stubbornly insist on the pursuit of zero-sum games of superiority in the interest of elusive and illusory ambitions of completeness? What happens when we are blinded to the reality that we are who we are thanks to the labour, material resources (natural and human), ideas and others’ generosity? Put differently, what happens if we systematically borrow without acknowledging, and refuse to recognise the reality of our debt and indebtedness to others? In other words, what happens when we ignore with impunity, the truth and humility of incompleteness, in how we relate with one another, be these human beings as individuals and collectivities, or between humans and objects and non-human? What are the consequences of repeated failure to see and provide for interconnections or fusions that provide for presence in absence and absence in presence in a manner that complicates our tendency to indulge in subject-object distinctions? The answer is simple: One can only get away with murder for so long. Sooner or later our impunities and excesses are bound to meet with fierce resistance – eruptions even – that we must reckon with willy-nilly. The #RhodesMustFall (RMF) movement of 2015 and 2016 in South Africa, was all about taking on such impunities. I have dwelled abundantly on this (Nyamnjoh 2016). Students at the University of Cape Town and other university campuses in South Africa, could no longer stomach the arrogance and racialised insensitivities that Rhodes’ imperial presence in the form of monuments and names of public spaces had come to represent despite the purported democratisation of post-apartheid South Africa.

De-nosed statue of Rhodes. Cape Town, 2020. Photo by author.

The RMF protest began on 9 March 2015 on UCT’s Upper Campus. Chumani Maxwele, a student, threw a bucket of human excrement at Cecil John Rhodes’ statue, which Njabulo Ndebele so eloquently describes above. Maxwele justified his action in these terms: ‘We want white people to know how we live. We live in poo. I am from a poor family; we are using portaloos. Are you happy with that?’.... ‘I have to give Cecil John Rhodes a poo shower and whites will have to see it’.[2] Following nearly a month of protests and meetings, the university senate voted in favour of moving Rhodes’s statue. A special meeting of the UCT Convocation on 7 April 2015 endorsed the decision. On 8 April 2015, the University Council unanimously resolved that the statue be removed. It directed that it be temporarily housed in an unnamed storeroom approved by the Western Cape Heritage Resources Council, pending a formal application to that council to permanently remove the statute, per the National Heritage Resources Act (Nyamnjoh 2016:145).

Was the removal and relocation the last of Rhodes as the epitome of ambitions of dominance, superiority and completeness on campus? Not exactly. Robert Mugabe seems to have been somewhat too optimistic when he thought he was doing Rhodes a favour by deciding to allow what he termed this ‘strange and mischievous man’, who had the habit of crossing borders without passports and disturbing the social systems of those he encountered, have his final resting place in the country once named after him. Responding to journalists during a state visit in Pretoria, amid the RMF protests, Mugabe declared: ‘We have his corpse and you have his statue’, adding, ‘We cannot tell you what to do with the statue but we and my people feel we need to leave him down there.’[3] It was never Rhodes’ intention to be deactivated by death. The reason why he fell in love with the Matopos Hills in 1896, was the inspiring words of King Mozelikatze who reportedly ‘asked to be buried in a sitting position’ at the Matopos Hills, ‘the highest point in his kingdom, so that even in death he could look at the magnificent vista before him’. Upon hearing the story, Rhodes had exclaimed, ‘What a poet’, and given instructions to be buried there as well (Maurois 1953: 137). Rhodes and his enthusiasts have refused to ‘leave him down there’. They have worked actively to defy death, by forging and maintaining links between the physically absent Rhodes and his fans and friends in present day South Africa, Zimbabwe, the UK and the rest of the world, many of whom have used him as their trump card. Put differently, his potency has not diminished with death. If Rhodes, like Tutuola’s skull, has continued to be activated and reactivated despite phenomenal contestations since his death in 1902, what reason is there to give the movement of 2015 and 2016 the last laugh in a zero-sum game of power and the illusions of completeness? If anything, the unnamed storeroom that temporarily houses Rhodes’ statue is more like the community of skulls in Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard. They continuously seek opportunities to activate themselves with new ambitions of conquest and the outsourcing of debt and indebtedness in a world warped by a logic of impatience with the reality of incompleteness and the humbling messiness of mutuality it proffers a template for conviviality.

Learning the Wrong Lessons from Rhodes

Little has changed since the 2015 and 2016 student protests. Rhodes is still firmly around even in his purported absence. Visible or not, Rhodes is amenable to activation and activating those who have kept his memory alive to enable their pursuit of potency for efficacy in their ambitions of dominance. It can be argued that little will change unless both those who praise or denounce, admire or mock Cecil John Rhodes are ready to disabuse themselves of the zero-sum games of superiority, conquest and delusions of grandeur that made him possible, and that have continued to activate and reactivate him even from beyond the grave. Simply put, one cannot beat Rhodes, his disciples and supporters through the winner-takes-all logic. That would entail a sort of unravelling and decomposition akin to that of the skull in Amos Tutuola’s story. Since such deactivation, if radically pursued amounts to the death of sociality, it is more productive to explore forms of conviviality informed by the recognition of incompleteness and provision for the humility that it inspires. Only in this sense that Rhodes and his legacy, be this in the form of statues, monuments, material and consumer culture or institutions, can be recalibrated to speak meaningfully to a sentiment expressed by former President Jacob Zuma during the #RhodesMustFall protests. For Jacob Zuma, although colonial symbols are not the most welcome sights, they constitute an essential part of South Africa’s history which cannot be obliterated, however painful: ‘When you read a history book and you come across a painful page, you do not just rip it out.’[4]

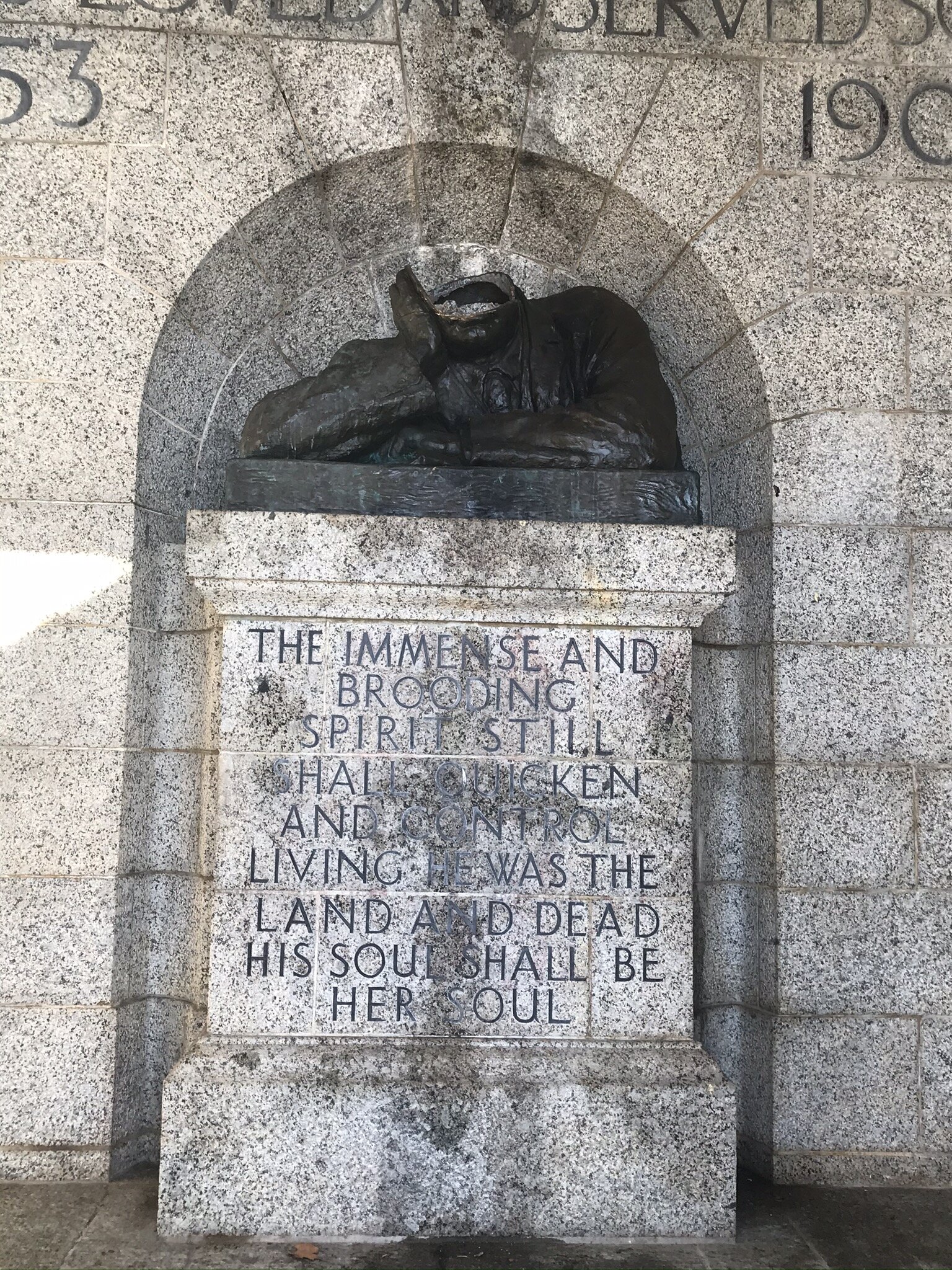

Until incompleteness is recognised and provided for in policy, public and private action, and the idea of conviviality and ubuntu embraced beyond token references and platitudes, experiences of counter violence on symbols of despicable impunities seeking to undo historic violence and violations inflected in the name of conquest, supremacy and their purported achievements would persist and grow. Occasional outbursts and symbolic acts of violence and vandalism by disgusted individuals and groups (identifiable or not), such as the cutting off of the nose in September 2015, the beheading or chopping off of the head in July 2020 of Cecil Rhodes from a bust at a memorial monument in his honour on the slopes of Table Mountain in Cape Town, would be commonplace, however great the investments in policing are. The symbolism of debt collectors angered by the skull had he like Cecil Rhodes decided to hang on to the body parts he had borrowed to activate himself and his ambitions is a potent one. Designed by Sir Herbert Baker and Sir Francis Macey[5] and completed in 1912, the ‘Rhodes Memorial consists of massive granite steps, flanked by bronze lions, and a rider astride a bronze horse at the beginning of the steps which leads to the top where the bust is situated’[6] Inscribed above the bust are the words:

TO THE SPIRIT AND LIFEWORK OF CECIL

RHODES WHO LOVED AND SERVED SOUTH AFRICA

1853 - 1902

Engraved beneath are the words:

THE IMMENSE AND

BROODING

SPIRIT STILL

SHALL QUICKEN

AND CONTROL

LIVING HE WAS THE

LAND AND DEAD

HIS SOUL SHALL BE

HER SOUL[7]

Statue freshly re-headed. Cape Town, 2020. Photo by author.

Statue weathered green after re-heading. Cape Town, 2020. Photo by author.

The Friends of Rhodes Memorial came to the rescue of the bust. They worked hard to ensure that the statue’s head was reattached and fortified in time for Heritage Day. They released a statement which read, inter alia: ‘In addition to restoring the head, all the sculptures at Rhodes Memorial have been 3D scanned and full-size replicas have been made as a replacement to counter any damage until the vandals are caught.’ The anti-vandalism measures installed included ‘the filling of industrial cement and iron in the statue as well as the installation of a GPS tracker and other electronic alarm systems.’ It hoped that such modern technologies of self-extension would not only protect Rhodes Memorial, itself a technology of extension of the good old days of the might of the British Empire and it global resonance, but combine forces to give alive such probed up superiority in the face of the growing questioning of imperial excesses and white supremacy by movements such as Black Lives Matter and in calls for reparations and the repatriation of artefacts and things of the colonies on display in museums and in other places and spaces in Europe especially, the foremost colonising continent.

Notwithstanding this obviously commendable rescue mission to those who praise and admire Rhodes for his accomplishments, no amount of re-heading and securitisation of the bust can effectively compensate for the call of incompleteness and conviviality. It is in recognition of this, perhaps, that Gabriel Brown, chairman of the Friends of Rhodes Memorial, was both pleased and realistic to have Rhodes’ head reinstated and fortified: ‘We are very pleased that the Friends of Rhodes Memorial Membership has grown tremendously’. He explained that each year hundreds of thousands of international and local visitors of all walks of life, races and religions, visit the monument. ‘They are all brought together by a sense of peace, harmony and nation-building,’ he affirmed. He was pleased that ‘Rhodes Memorial … one of the finest monuments in the world, … is here in Cape Town.’ Conscious of the controversy around the monument, he added: ‘Perhaps we could have two plaques on either side of the bust, the good and bad side of Rhodes.’[8]

Rhodes Grave at the Matopos Hills. Photo by Janet Mate.

Conclusion

I would like to begin my conclusion with sharing with you an email reaction by Jean-Pierre Warnier, a friend, teacher and mentor through the years, as food for thought, when I shared with him this paper. In an email to me on February 8, 2021, he wrote:

Dear Francis,

Thanks a lot for the impressive text.

I have been invited to Kirghizstan as a prof several years in a row, a former colony of the Tzars and of the USSR. I admired the way they dealt with the statues and symbols of both. For example, on Chuy Prospect, the immense avenue where the military Stalinian parades took place in the capital town of Bishkek, there was a monumental statue of Lenin lecturing the crowds. After 1990 and the collapse of Soviet Union, they did not destroy it. They replaced it by a statue of Freedom and moved it to the other side of the National Museum, just in front of the vacant seat of the now defunct Communist Party.

Now, when a consortium of American Universities (from the USA) decided to establish an “American University in Central Asia” (AUCA) the government offered the huge Stalinien building of the Communist Party to the new University with the obligation to keep the facade with hammer and sickle, flags carved in stones on both sides, a couple of Proletarian holding them, a mast and the red star on top. The AUCA was allowed to write in huge golden letters on the facade “American University in Central Asia”. The result is that the monumental statue of Lenin lecturing the crowds is now lecturing the AUCA in the seat of the defunct Communist Party with all its paraphernalia. Mind you, most Kirghiz are nostalgic of the Soviet Empire from which they benefited to a large extent, and they fear and loath the Chinese neighbor.

This is a rare but brilliant case of recycling various symbols with scorching irony. There must be many instances of that kind of piling up together of different kinds of references. One of them comes to mind. It is that of the “Marseillaise”, the French national anthem. The text was written by Rouget de Lille, a Captain in the French army, and a amateur poet. It was written and immediately published in April 1792 as the French Revolution was well under way, in the context of the war against Austria. The tune was that of the Catholic anthem Tantum ergo... in praise of the Eucharist, that was sung in all the churches all over the country. There was not a single French man or woman who didn’t know the tune. The text was printed in thousands of copies and people who knew how to read could sing the new Marseillaise straight away on the tune of the Tantum ergo. Instead of abolishing the Catholic religion, you use it to promote the cult of the Nation and the homeland. Clever indeed.

Warm regards,

JP

L (top and bottom) - The vacant seat of the Kirghiz Communist Party, handed over to the American University in Central Asia (AUCA) around 2000. The AUCA has added its name to all the emblems and paraphernalia of the Communist Party. R (top) - Lenin faces the University, to the other side of the street. R (bottom) - A tall column at the centre of the large plazza, with Chuy Prospect avenue in the foreground and the national flag in the background to the left, two soldiers mounting guard by the mast. On top of the column there is a statue of freedom (or Liberty) that replaced a statue of Lenin, removed after the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The column stands in front of the National Museum, a white cubic building at the background. Bichkek, Kirghizstan, October 2005. Photos by Jean-Pierre Warnier.

The Kirghiz example of recircled symbols is an acknowledgement that we inhabit a dynamic world of creative diversity and interests in which no one, society, culture or civilisation has the monopoly of ingenuity, power, privilege and right to life and dignity, and that turning the tables on one another is most productive when disabused of the temptation, however fleetingly or spur-of-the-momently compelling and justifiable, of throwing the baby out with the bathwater of oppression, suppression and repression. Just as we must disabuse ourselves of all ambitions of dominance that are driven by illusions and delusions of completeness.

Yet, much as accommodation and inclusiveness are the clarion call of sanity with great promise for the future of South Africa, for existing colonial statues and monuments to signify anything but oppression and dispossession, they would have to be actively and consciously re-articulated, recalibrated and reconfigured into multicultural and dynamic symbols of truth and reconciliation. This calls for humility and alertness to the sensitivities and sensibilities of the various shades of the imagined dream of a rainbow nation. It may be up to every South African to be the change for which they aspire, by demonstrating the extent to which they are willing to embrace incompleteness, recognise the place of debt and indebtedness in being and becoming, and disabuse themselves of the violence and illusions in ambitions of completeness as a zero-sum pursuit.

In terms of race relations, change can come about only if whites and whiteness as epitomes of privilege and supremacy in South Africa move from quibbles and rhetoric to real gestures of inclusivity through significant recirculation of the wealth and resources amassed because of the injustices and inequalities of colonialism and apartheid. Rhodes and his contemporaries were forerunners of these. The case for restitution and reparations or redistribution has never been more urgent.

Those who harness their intellect, art, skills, efforts and time to foster greater social and cultural integration with selflessness and commitment to a common humanity, and who are recognised and encouraged for doing so, point to a future that is neither trapped in delusions of superiority nor in the celebration of victimhood. However, the failure to enforce greater integration beyond elite circles combines with ignorance and arrogance to guarantee continuation for racism and prejudices. Apartheid might have died officially, but slow socio-economic transformation and slow reconfiguration of attitudes, beliefs and relationships favouring greater mutual recognition and accommodation have meant its continued reproduction in less obvious and more insidious ways. It is through recognition of the capacity of all and sundry in South Africa to act on others as well as to bear the actions of others in time and space that an appropriate citizenship inspired by the universality of incompleteness, mobility, debt and indebtedness actualises beyond the pages of a generous constitution. Such citizenship is far from possible in contexts where the myth of self-cultivation, self-activation and self-management is uncritically internalised and reproduced in abstraction with effortless abundance. There is promise in a citizenship inspired by the imperatives of the universality of incompleteness not as a negative condition that must be transcended, but as a reality and disposition with enormous potential for efficacy in action and interaction among a myriad of incomplete sentient beings.

References

Baker, H., (1934), Cecil Rhodes, London: Oxford University Press.

Brown, R., (2015), The Secret Society: Cecil John Rhodes’s Plan for a New World Order, Cape Town: Books (Penguin Random House South Africa).

Flint, J., (1974), Cecil Rhodes, Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Hyam, R., (1976), Britain’s Imperial Century 1815-1914: A Study of Empire and Expansion, London: B.T. Batsford.

Maurois, A., (1953), Cecil Rhodes, London: Collins.

Nyamnjoh, F.B., (2016), #RhodesMustFall: Nibbling at Resilient Colonialism in South Africa, Bamenda: Langaa RPCIG.

Phillips, H., (1993), The University of Cape Town 1918-1968: The Formative Years, Cape Town: UCT in association with the UCT Press.

Plomer, W., (1984 [1933]), Cecil Rhodes, Cape Town: David Philip.

Roberts, B., (1987), Cecil Rhodes: Flawed Colossus, London: Hamish Hamilton.

Tutuola, A., (1952), The Palm-Wine Drinkard, London: Faber and Faber.

Tutuola, A., (1954), My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, London: Faber and Faber.

Endnotes

[1] Njabulo Ndebele, ‘Reflections on Rhodes: A story of time’, http://www.uct.ac.za/dailynews/?id=9038, accessed 6 October 2015.

[2] See Steven Robins, http://www.iol.co.za/news/back-to-the-poo-that-started-it-all-1.1842443#.VlvZRb-3ud8, accessed 30 November 2015.

[3] See http://www.bdlive.co.za/national/2015/04/09/zimbabwe-will-let-rhodes-lie-says-mugabe , accessed 17 September 2015.

[4] http://www.news24.com/Archives/City-Press/Zuma-tackles-colonial-statues-xenophobic-attacks-20150429; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=draGELk8grU , accessed 6 October 2015.

[5] ‘The day Cecil John Rhodes lost his head,’ by Donwald Pressly, 15 July 2020, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-07-15-the-day-cecil-john-rhodes-lost-his-head/

[6] ‘Cecil Rhodes 'beheaded' at Cape Town monument,’ by Naledi Shange and Andisiwe Makinana, 14 July 2020, https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2020-07-14-cecil-rhodes-beheaded-at-cape-town-monument/

[7] These are an ‘excerpt from a tribute by British author Rudyard Kipling, a contemporary of Rhodes’, see ‘South African bust of Cecil Rhodes loses nose to vandals,’ 21 September 2015, https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/south-african-bust-of-cecil-rhodes-loses-nose-to-vandals-115092100551_1.html, accessed 02 January 2021.

[8] ‘Rhodes Memorial statue’s head reattached, fortified and replica made after vandalism,’ https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/western-cape/rhodes-memorial-statues-head-reattached-fortified-and-replica-made-after-vandalism-ffe1a806-c8c0-4231-8353-ccf791c0ff81, accessed 29 September 2020.