Interview with Sedekah Benih – Urban Ecology and Community-based Art Activism

Abstract

Sedekah Benih is a collaborative and urban environmental practice initiated by an urban farming activist, Dian Nurdiana (Mang Dian), and artist Vincent Rumahloine in 2020 in one of the dense urban neighborhoods in Cibogo, Bandung, West Java. It aims to share and exchange knowledge of urban farming more widely and build a community of “tiis leungen” (Sundanese for “cold arms”), a term comparable to the English “green thumbs”. Drawn from a localized Arabic word and concept of صدقة (sadaqah), which means “righteousness” and refers to the giving of charity, Sedekah Benih aims to share seeds of everyday staple plants that can be grown in dense community spaces and used for local and domestic needs as a direct response to the increased prices of these staple products in the market. Its core activities encourage the collaborators to share the seeds of plants they received with others from their communities and, thus, ideally, grow connected community nodes that are organic and always moving.

Since the start of its planting during the height of the pandemic, Sedekah Benih has worked with communities in Cibogo and beyond, pulling in different modes of growing and activating the seeds, such as the local Sundanese karinding music group. The project also traveled outside Cibogo and Indonesia as part of an international event in Germany, the Driving the Human project. While the activism itself is largely informed by Islamic concepts, Sedekah Benih is also premised upon openness to transcultural and interreligious dialogs and different methods of growing and sustenance. This short essay contextualizes the story of Sedekah Benih through Mang Dian and Vincent as they articulate and realize their project.

Citation: Rahadiningtyas, Anissa. “Interview with Sedekah Benih – Urban Ecology and Community-based Art Activism” The Jugaad Project, 28 September 2022, www.thejugaadproject.pub/sedekah-benih [date of access]

I. The Pandemic and the Skyrocketing Price of Chili Peppers

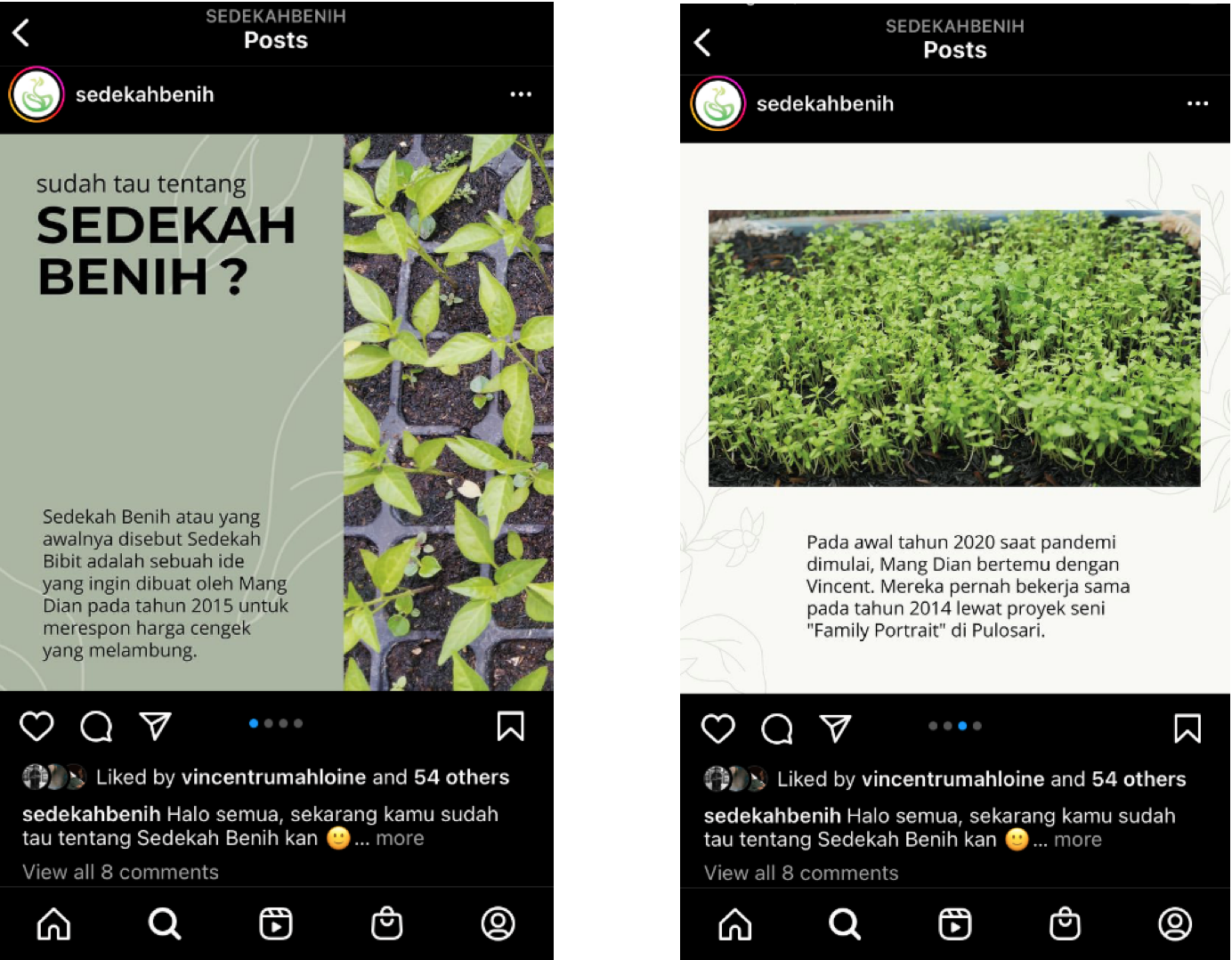

Figure 1. “Do you know about Sedekah Benih?” Sedekah Benih Instagram post introducing the beginning of the community-based art and environmental project. Image courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

Sedekah Benih Instagram (started 10 July 2021) introduced how the project began. It was the end of 2020 in the early days of the pandemic when Dian Nurdiana (Mang Dian) and Vincent Rumahloine began to work together on a short documentary project to record every day realities of the pandemic. This government-sponsored project was a prelude to their present-day collaboration as it began with Vincent producing a short video on Mang Dian’s urban farming project with the santris (students at Qur’anic schools or mosques) at a local mosque in Cibogo. “The theme of the documentary was about food security, and I remember stalking and engaging with Mang Dian’s urban farming activity through social media,” Vincent recalls. Mang Dian’s urban farming projects that involved sharing seeds of staple plants started in at least 2015 when he worked to plant vegetables, like chili peppers, kangkong (water spinach), and green onion, on concrete roof decks of houses and buildings in Bandung using polybags and pots, including on the roof deck of a local mosque. To the santris, Mang Dian supplied and taught how to prepare the seeds, soils, and organic fertilizers. He recounts, “I then said to the santris and the ustadz (religious teacher) that it is up to them whether they would want to sell the products or to give them to sedekah (charity). I think this is the first time I realized the ubiquity of the word sedekah.” Since then, Mang Dian named his urban farming project “Sedekah Bibit” (trans: Sharing of Seeds) before it changed to “Sedekah Benih” after his chat with Vincent during the pandemic.

Figure 2. Sedekah Benih Instagram posts on Mang Dian’s project of planting the chili pepper. Image courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

The fluctuating price of chili peppers over many years and its extreme increase in 2017 became one of the reasons for Mang Dian’s persistence in his urban farming projects. Chili is considered an essential for many Indonesian communities as shown by the diverse varieties of sambal (chili sauce or paste) made in both homes and restaurants. Every holiday celebration of either Eid al-Fitr or Christmas is usually accompanied by the rising price of chilies due to the increased demand for this pepper in the market, followed often by disgruntlement. In 2017, a record-breaking high was set with the price of chili peppers soaring as high as ID Rp. 200,000/kg (approx. USD 14.76/kg).[1] While not as high as it was in 2017, the price of chili peppers in mid-2022 experienced a significant increase to Rp 140,000/kg (approx. USD 9.49/kg) in Jakarta, partly but significantly due to the spread of a disease that decreased the harvested stock to 50-60%.[2] Due to the preference for fresh peppers, the strategy of buffering stock by turning fresh chillies into a dried product failed. To offset the impact of the price increase this year, President Jokowi ultimately urged the people to plant chilies in their backyard to meet domestic needs.[3]

After the documentary project with Mang Dian, and at the prospect of not having anything else to do because of the pandemic but his graduate school assignments in Bandung, Vincent then urged Mang Dian, “ayolah Mang, kita bikin apa yuk!” (“Let’s make something, Mang!”), and recalled,

We were thinking of doing something that is relatively simple but has benefits for many people. That was when Mang Dian told me about Sedekah Bibit. I offered him my contribution as an artist to visualize and contextualize the project so that it could have a broader impact. Initially, Mang Dian’s idea to share the seeds of chili peppers during the period when the cost of the pepper was increasing was very simple. But then we thought we could broaden this to address issues of food sovereignty politics.

Figure 3. Vincent Rumahloine’s documentation of his previous work, Kuncen Leuwi (2014-2015), Bandung. Image courtesy of the artist.

Initially trained in the Ceramic Studio at the art institute in Bandung (2009), Vincent gradually moved away from making object-based works to creating community-based collaborations. From volunteering at Rumah Cemara where he worked with marginalized communities and urban issues in Bandung, he ventured to an area called Pulosari in Bandung where he met with Mang Dian and the Kuyagaya community. The Kuyagaya community and their work in cleaning the river in Bandung while also monitoring the water debit in the river upstream and setting up an early warning system for downstream flooding prompted Vincent to create a large-scale photograph installation displayed along the walls by the river. Titled Kuncen Leuwi (Guardian of the River) (2014-2015) it captured the individual faces of the community in a series of photographs, enlarging them as big as the banners that commonly depicted politicians and celebrities. When the pandemic began to hit Bandung severely and stopped many exhibition and art residency projects, Vincent and Mang Dian found an opportunity to share and collaborate through Sedekah Benih.

II. Growing Tiis Leungen, Expanding Connections

Figure 4. Open Call for Tiis Leungen. The call for open participation for people to get their share of chili pepper seeds, organized by the Goethe Institut in Bandung. Image courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

Initially self-funded with Mang Dian providing labor and Vincent helping with buying seeds and plant growth medium, Sedekah Benih kicked off in February 2021 by planting 100 seeds of chili peppers. To further broaden the project, Vincent and Mang Dian sent the proposal for Sedekah Benih to the Goethe Institut in Bandung and to a multidisciplinary eco-social platform led by major institutions in Germany, including the Ministry for the Environment, called Driving the Human. DGoethe Institut in Bandung, Vincent and Mang Dian started their work by sharing the 100 seeds that they had planted with friends and acquaintances. The initiative to grow 100 seeds of chili peppers aims to cultivate what is locally known in Sundanese as tiis leungen (trans: cold arm), a term comparable to the English “green thumb”. With the help of the Goethe Institut in Bandung, Vincent and Mang Dian shared the seeds with participants – or what they also call “adopters” – from September through November 2021. Through these seeds, adopters and collaborators can simply engage in conversations and share knowledge with each other and their neighbors that are certainly not limited to growing chili peppers seeds. For Mang Dian and Vincent, it is precisely the aspect of communicating that they seek – “that people can talk to each other, to share stories and seeds, and thus strengthen silaturahmi,” Mang Dian emphasized. Localized from the Arabic word, “silaturrahim,” silaturahmi in Indonesian refers to the “thread of friendship; and/or comradery.”(4)

Figure 5. Community of ibu-ibu (women) in Cibogo making little pots from banana leaves to plant seeds of kangkong (water spinach) and chili peppers, June 2022, photographed by Djuli Pamungkas. Image courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

Figure 6. Community of ibu-ibu (women) in Cibogo building their own greenhouse using bamboo, June 2022, photographed by Djuli Pamungkas. Image courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

Sedekah Benih activities integrate seamlessly into existing environmental initiatives that Mang Dian leads in his neighborhood in Cibogo. As Mang Dian relied on the energy and networks of emak-emak or ibu-ibu (a group of usually married women, although it generally also refers to women) in his densely populated neighborhood,(5) Sedekah Benih also taps into the power and organizational prowess of the group. Prior to and along with Sedekah Benih, ibu-ibu in Cibogo also organized a weekly Jumat Bersih (Friday Cleaning) where they cleaned the streets and sewers in the neighborhood. The role of emak-emak or ibu-ibu is crucial within a community as they hold the power to effect changes within their family domain, which subsequently expands into the neighborhood. Their working model is often organic with no fixed hierarchical structure and members, making it open, reliable, and ever-changing. Vincent remarked,

I see that ibu-ibu have a crucial position in making changes in society, particularly in densely populated areas. So, they are very important for Sedekah Benih. If we can attract their interest, they can at least introduce [our activities] to their children, and it is only a matter of time before [our ideas] can be accepted by everyone. But the most important thing to note is that we have to approach them using everyday things and language. If we use complicated methods, they would probably think that we are wasting their time. For the sustainability of Sedekah Benih programs, ibu-ibu are important agents as they can easily organize many things organically within their communities. If we want to change society, I think we have to think about working initially with ibu-ibu because they are in charge of the domestic space. Once they can make small changes within their home, they can shift the direction of the whole house. [We also found] that it is more difficult for men to commit to [our] activities.

Mang Dian added, I am grateful that it did not take a long time for ibu-ibu to continue the environmental programs without me being present. They are very independent in running all the programs.

Figure 7. Activities of ibu ibu in the Masagi community in Cibogo, Bandung, from cleaning the neighborhood to communicating their needs and aspirations to government officials in Sedekah Benih’s discussion program called Sabulang Bentor. Image courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

The community of ibu-ibu in Cibogo is the starting point for the Sedekah Benih community-based project that currently involves five communities of tiis leungen across Bandung. In Cibogo, the community set up their own greenhouse in the back of one of the resident’s houses to grow several plants, including chili peppers, kangkong, green onions, and papayas. The four other communities of Barangkal Farm in Cibogo, Kebun Komunitas run by the trans community in Cimahi, Kebun Pulosari in Pulosari, and Kebun Puzzle run by the LGBTIQ community in Kiaracondong further expand the ever-growing connections and networks of tiis leungen that also embrace the often-marginalized communities in Bandung and Indonesia.

Figure 8. Karinding concert by members of Karinding Keos during the mitembeuyan ritual at the start of the planting phase at the local community farm in Cibogo on 19 April 2022, photographed by Choirul Nurahman. Image courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

Sedekah Benih’s emphasis on making connections also exposed them to different modes of growing, including the one based on local Sundanese knowledge and eco-cosmology through karinding music.(6) Similar to the jaw harp, Karinding is a Sundanese musical instrument made of bamboo played by putting the top part on the lips and flicking the end of the instrument to create a vibrating sound. Karinding is traditionally played during the planting period, bestowing the growing rice with musical “prayers of the Mightiest God,” which is purportedly believed to be the meaning behind the term karinding.(7) Often accompanied by other Sundanese musical instruments made of bamboos, such as kendang, celempung (both percussion-type instruments), and goong tiup (a wind instrument similar to the Indigenous instrument of Didgeridoo from Australia), it is believed that the sound produced by karinding has a frequency that is beneficial for growing plants.

Figure 9. Sedekah Benih’s Instagram posts introducing and circulating information on the philosophy of karinding through social media. Images courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

The chance meeting with karinding players happened when Sedekah Benih was working together with members of Bottlesmoker to give the planted chili seeds a concert at Goethe Institut when the seeds were eight days old. This was an idea to further popularize Sedekah Benih, and for the activities to reach broader communities. Bottlesmoker is an electronic music band in Bandung whose research and practice on the influence of certain frequencies in helping plants to grow interested Mang Dian and Vincent.(8) During this process, Vincent also met with Dadang Kurnia (also known as Mang Aseng), who happens to be a karinding player in a bamboo folk metal band called Karinding Keos. They met while hanging out with members of a village-level youth organization known widely in Indonesia as Karang Taruna in his neighborhood in Setiabudi, Bandung. For Sedekah Benih, Karinding Keos focused on performing the karinding element, as seen in the photograph of the mitembeuyan ritual (Sundanese fertility ritual for plant growing) at the local community farm in Cibogo (fig. 8).

Concert for plants at the Goethe Insitut Bandung by Karinding Keos, Gentra Wirahma, and Bottlesmoker, 27 September 2021. Video courtesy of Sedekah Benih and Everything in Between.

From Mang Aseng, Vincent and Mang Dian learned about the importance of karinding and local eco-cosmology as mapped onto the instrument itself. The three parts of karinding instrument map three types of nature and forest within local geographical and cosmological systems, distinguishing the one that can be cultivated, one that can be lived in but needs to be protected, and one that cannot be touched at all. Ensuring a balance between these three spaces of life is of the utmost importance. Vincent further relayed the conversation with Mang Aseng on karinding,

Karinding is traditionally played before and during the planting of rice and other plants. It is believed that playing karinding can enhance the growth of plants. There are a few patterns of sound made by a karinding instrument. One of the patterns is used as an opening to communicate with and ask permission from the spirits and animals that inhabit the land used for planting, as humans are merely guests. After the planting, a different pattern of karinding is then played again to enhance the plants’ growth and repel pests.

I think the intersection between the scientific research by Bottlesmoker and the local belief system as embedded in karinding music is fascinating as they have a common ground in the importance of sound frequencies in planting and growing plants.

Figure 10. Screenshot from the Driving the Human project page showing Sedekah Benih as one of the selected concepts. Sedekah Benih proceeded to become one of the seven prototypes for “… shaping sustainable and collective futures that combine science, technology, and the arts in a transdisciplinary and collaborative approach.

The impulse and intention to grow and expand connections through different means are behind every activity of Sedekah Benih. During the initial stage of the Driving the Human project in October 2021, Vincent represented Sedekah Benih as one of the twenty-one selected projects and built a greenhouse to grow seeds of lamb lettuce plant to share with visitors and other collaborators in Germany. Similar to the seeds planted in Bandung, the lettuce lamb seeds also listened to the karinding music before being given away to the audience. To further connect the different communities across the globe, adopters of tiis leungen in Germany were encouraged to join Sedekah Benih’s online platform and forge a relationship with tiis leungen in Indonesia with the possibility of sharing the harvest event of the lettuce lamb in Germany and the chili and red ginger in Bandung simultaneously.(9)

Figure 11. Sedekah Benih’s open call for a sambal competition that attracted 135 sambal entries. The final judging period is now underway. Image courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

The latest Sedekah Benih activity is currently underway, a chili sambal competition where 135 sambals from diverse households in Bandung entered the race for cash prizes and the title of the best sambal. The competition is designed to create a fun event and target new communities outside of those already working with Sedekah Benih, a proposition to continue sharing the seeds of chili peppers as people are reminded of the utmost importance of chili and sambal in local culture and cuisines.

III. Sedekah Benih: Collaborating as Everlasting Act of Sharing

Figure 12. Mang Dian sharing the seeds of cengek (Sundanese for chili peppers) with the students of Qur’anic schools in Bandung. Image courtesy of Mang Dian.

Mang Dian:

Since I was a little kid, I remember that my father taught me the rather simple concept of bakti and bati. He taught me to prioritize berbakti (Bahasa Indonesia: to serve dutifully) and not to pursue bati (Bahasa Indonesia: material profit).

The purpose of using the term sedekah for me is to prompt the act of sharing. While the term itself might be more strongly affiliated with a certain religious practice, it is used rather widely [in Indonesia] nowadays. We use the term sedekah to promote the act of sharing, planting, and re-sharing things that are not limited to money or material things, and we emphasize the idea that collaborating is already a form of sharing.

Mang Dian understands collaboration (Bahasa Indonesia: kolaborasi) as the contemporary equivalent of a widespread and long-standing pan-Indonesian practice and spirit of gotong royong. Loosely translated from its Javanese origin, gotong royong is the act of mutual assistance and reciprocity, traditionally within an agricultural society. As John Bowen succinctly puts it, gotong royong is often imagined as “… social relations in a traditional, smoothly working, harmonious, self-enclosed village of Java, where labor is accomplished through a reciprocal exchange, and villagers are motivated by a general ethos of selflessness and concern for the common good.”(10) While the notion of gotong royong initially embodied genuine moral obligation and generalized reciprocity, Bowen noted how gotong royong had been utilized by various political actors in post-independence Indonesia to mobilize labor, galvanize and construct a false sense of united actions, disguise uneven power relations, and mask the state’s authoritarian intervention into village lives particularly during the New Order period, as it further occupied the national political stage.(11)

Mang Dian and Vincent’s Sedekah Benih initiatives return the grassroots practice of gotong royong to the villages – the densely populated urban villages in Cibogo and other parts of Bandung. For Mang Dian whose environmental initiatives hardly attracted interest and support from government officials, Sedekah Benih became the needed method and strategy to be able to continue sharing ideas, knowledge, and the goal of community self-sufficiency, especially in densely packed urban areas with less access to arable land. However, they are currently facing the constant anxiety of losing the few acres of land the community in Cibogo is cultivating due to potential change in ownership.(12) Limited land is always an issue in densely populated areas like Bandung, West Java. A few plans are currently being devised by Vincent and Mang Dian to anticipate such (inevitable) changes by approaching the neighborhood mosques in the hope of using their yard for planting and growing community gardens. Another solution is to grow gardens on each of the resident’s roofs, just like Mang Dian did with his first project on the rooftop of the mosque in Cibogo. This plan, as Vincent contemplates, could change the community’s mode of togetherness as people would grow plants separately.

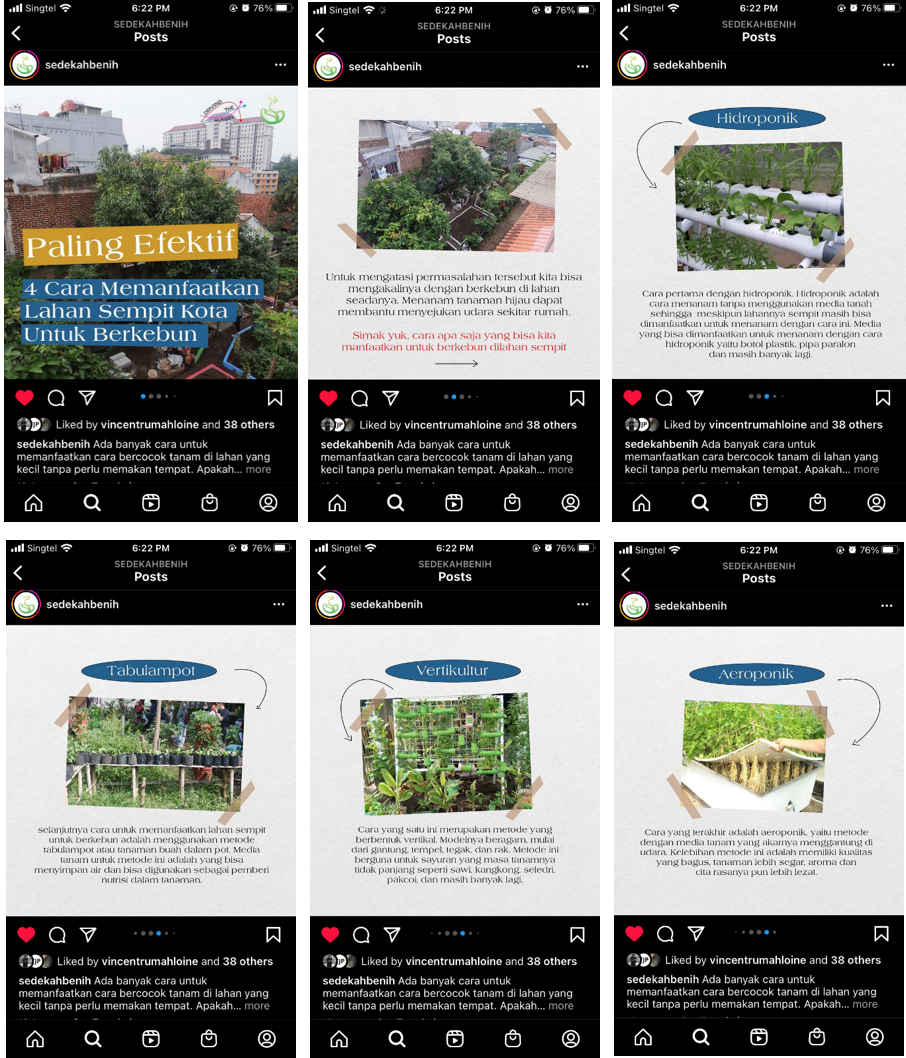

Figure 13. Sedekah Benih Instagram page sharing tips and techniques for growing staple plants in limited urban space, such as hydroponic, using recycled plastic pots, verticulture, and aeroponic. Images courtesy of Sedekah Benih.

As a platform to learn and share knowledge that expands beyond planting and growing plants, Mang Dian and Vincent emphasise the spiritual and religious aspects behind their activism; the importance of maintaining a balanced relationship between human needs and the environment, and to mindfully cultivate and grow food. As a Muslim, Mang Dian is informed by the importance of maintaining a good relationship between humans and other beings to establish a vertical relationship with God:

While the vertical relationship with God or habl al minallah is important, it is not the only focus as there needs to be a balance between a vertical devotion to God and building a relationship with other human beings or habl al-minannas. Without building a good relationship with other human beings, then [my] life would not achieve anything significant. The best humans are those who benefit other human beings. This is my principle in life. In addition to a good relationship with other human beings, we have to strive for a good relationship with other beings, including plants, animals, soils, and water. … The key is the balance (Bahasa Indonesia: keseimbangan) between all three relationships.

Vincent adds another perspective based on what he learned together with Mang Dian during the year of running Sedekah Benih:

I believe that everything has its order in many belief systems. When we learned about local Sundanese cosmology, we saw similarities in the emphasis on the importance of balance and bakti towards nature as God’s creation. One has to berbakti to nature in order to berbakti to God. We also learned that in the Sundanese eco-cosmological concept, human is positioned as equal to other beings – to plants and animals. In their cultivation practice, it is important to ask for permission from the land, the animals, and the spirits that occupy the land way before us. It shows that humans are not the owner of lands and, therefore, cannot exploit them; we are only temporary guests.

I think the way Mang Dian explained how to keep the balance between the relationship with God, with humans, and with nature is very accessible, especially in the socio-religious context of Indonesia. Even though we share different faiths, I also believe that everything in the universe is connected, and there is always a spiritual dimension beneath everything; and that is why we believe that Sedekah Benih is not only about [caring] for the environment.

Utilizing the term sedekah ensures the accessibility of Sedekah Benih’s foundational concept, and “… a more successful way of encouraging active participation rather than using foreign terms like “urban farming” … as [sedekah] has a close association with religious practice,” as Vincent elaborates. For Mang Dian and Vincent, collaboration prompts the act of sharing knowledge and experience, which subsequently turns into a concrete sharing of material things, such as seeds, music, and food. Sedekah Benih’s core idea, therefore, is to encourage and maintain the spirit of collaboration, and of collaboration as an act of continuous sharing (of seeds, foods, and documentation of events) that transpires beyond the borders of urban villages in Bandung.

Endnotes

[1] Septian Deny, “Pertama Kali dalam Sejarah, Harga Cabai Tembus Rp 200 ribu per Kg,” Liputan 6.com, 5 January 2017.

[2] “Lonjakan Harga Cabai Bakal Kerek Inflasi,” Kompas.com, 23 July 2022; see also, Andi M. Arif, “Harga Cabai Meroket karena Produksi Anjlok hingga 60%,” katadata.co.id, 17 Juni 2022.

[3] “Minta Masyarakat Tanam Cabai, Jokowi: Biar Nggak Kekurangan atau Harga Naik,” Kompas.com, 11 August 2022.

[4] https://kbbi.web.id/silaturahmi, accessed 28 August 2022, 13:52 SGT.

[5] “Emak-emak” and “ibu-ibu” are two terms used synonymously referring to the same meaning, but “emak-emak” is often considered less formal and more local, while “ibu-ibu” is more formal.

[6] Sundanese is one of the large ethnic groups in Java that resides largely in the West Java area, although they can be found in several other islands through migrations and intermarriages. Like the Javanese, Sundanese culture also revolves around agricultural lives. While many Sundanese has adopted Islam as a religion, there are still a few groups, such as the Baduy, whose religion of Sunda Wiwitan (early Sunda) retains local religious practices with very little influence from Islamic or even Hindu-Buddhist belief systems (see Wessing 1978).

[7] As shown in Sedekah Benih Instagram post on the philosophy of karinding, the term karinding is believed to come from the phrase, “ka ra da Hyang,” which means “accompanied by prayers from the Mightiest God.” Generally, karinding instrument is about 10 cm long, divided into three segments of the upper, middle, and lower parts. While the parts correspond to how the instrument is positioned and played, the segments are also indexes to the local Sundanese eco-cosmological map.

[8] See Bottlesmoker’s performance here (youtube link)

[9] See the full essay and interview of Sedekah Benih for the Driving the Human project in Aisha Altenhofen, “Plants as Language, Humans as Seeds,” Driving the Human, accessed 1 September 2022.

[10] John R. Bowen, “On the Political Construction of Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia,” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 45, no. 3 (May 1986), p. 546.

[11] Bowen, ibid, pp. 546-555.

[12] Vincent Rumahloine, WhatsApp conversation with the author, 21 September 2022.